I’m

Deborah Roberts: I’m

Museum of Contemporary Art Denver

1485 Delgany Street, Denver, CO 80202

September 10, 2021-January 30, 2022

Admission: Weekends: Free; Weekdays: $10; College Students (with ID), Seniors 65+, and Military: $7; Teens and Children: Free

Review by Renée Marino

In an interview with artist the Deborah Roberts for Art in America, Joshua Bennett writes “there are worlds outside, alongside, underneath, and above the anti-Black world”. [1] As a Black woman, born in 1962 in Houston, Texas, Roberts has experienced many of these worlds, and creates new ones in her compelling, large-scale, mixed media works. Primarily, she chooses Black children as her central subject.

An installation view of Deborah Roberts’ exhibition I’m at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the MCA Denver.

Roberts’ work has been collected by a handful of notable museums, including the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and Los Angeles County Museum of Art in California. Her latest exhibition, I’m, is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver until January 30th, 2022. Using a combination of acrylic paint, collaged found faces, and ink, her works carry worlds of meaning. “I want us to see ourselves as a heroic people,” she says. [2] I’m speaks directly to the humanity of being, specifically being Black. Through I’m, Roberts not only brings new, meaningful representations of Black children into a cultural conversation, but further implores viewers to witness cultural expectations of Blackness, through the eyes of a child.

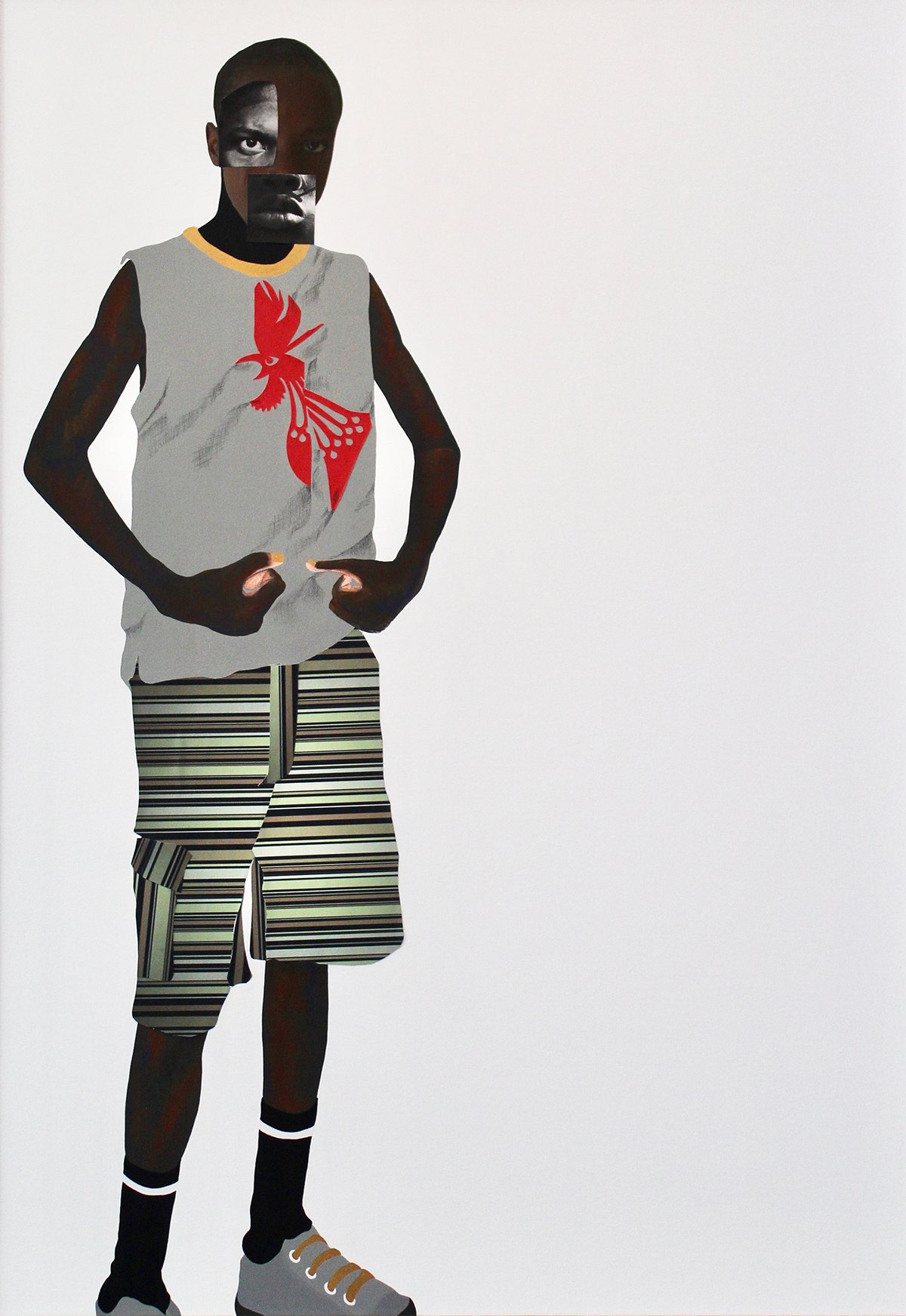

Deborah Roberts, Cock-a-doodle-do, 2019, mixed media collage on canvas, 65 x 45 inches. Image by Renée Marino.

In Cock-a-doodle-do, a Black boy stands facing the viewer, flexing his arms and clenching his fists. His head is shaved. He wears a sleeveless shirt with a bright red rooster on it, striped shorts, tall socks, and tennis shoes. The boy’s face is collaged with a mouth and eye not his own, intensifying his gaze and lips. Meanwhile, his body looks harmless, youthful, and petite. The contrast in content and character brings to mind a double standard. Black boys are hyper-masculinized and subsequently criminalized. The boy in Cock-a-doodle-do is the sole figure, alone on the canvas, bringing to mind how Black boys are taught to assert their power and independence for their own survival, and too often condemned to death for the same.

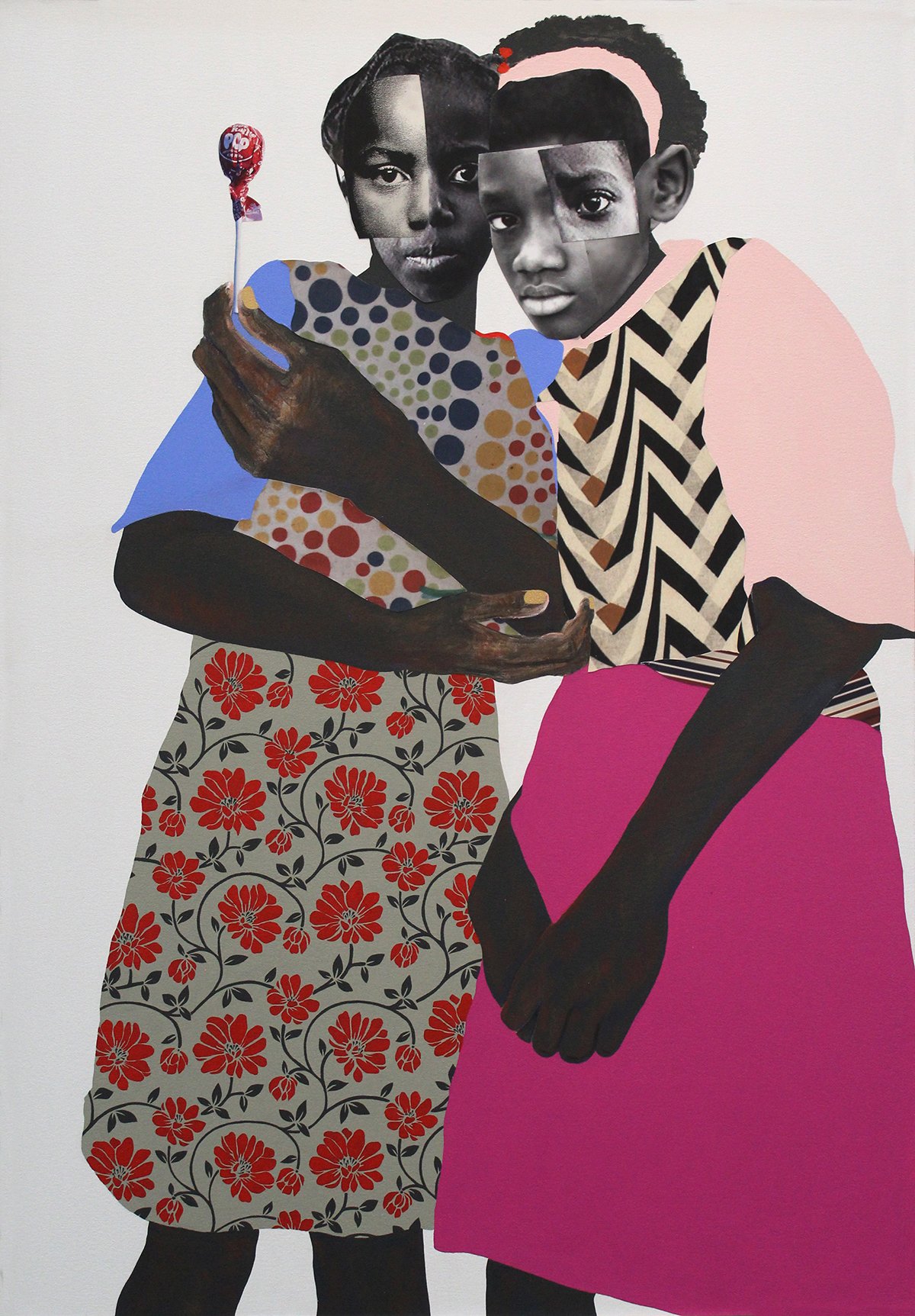

Deborah Roberts, The unseen, 2020, mixed media collage on canvas, 65 x 45 inches. Image by Renée Marino.

Not far off from this work, we encounter an image of two Black girls in brightly colored garments who stand together. The girl on the left with cradled arms, bigger than they ought to be, holds a Tootsie Pop as if it’s appeared by magic. The other girl leans in; the deep look of her paper eyes calling the viewer to task. This composition, The unseen, sears it’s imagery into the viewer’s mind. Roberts has chosen bright, contrasting colors and patterns. The girls’ faces come together seamlessly, even with their collaged gradients, atop the stark white background. What’s unseen are Black girls writ large. Tenaciously looking back at the viewer, Roberts’ brings these Black girls to the center of our minds and hearts.

The Tootsie Pop featured in The unseen also appears in two other works in the exhibition: Good trouble and The duty of disobedience. The Tootsie Pop is a common experience of childhood, and what’s more, the Tootsie Pop’s hard exterior and soft, chewy interior, might just be a metaphor. In Roberts’ works, the Tootsie Pop evokes the feelings of childhood—an innocence and playfulness which all children deserve to experience. It also speaks to the outer toughness Black children are socialized to exhibit, while their interior world and spirit remains immensely vulnerable.

Deborah Roberts, The looking glass, 2019, mixed media collage on panel, 60 x 48 inches. Image by Renée Marino.

In The looking glass, Roberts' repeated interrogation of her subject's gaze becomes undeniable. The figure, a young child, tilts their head sideways. They hold up two fingers on both hands to make a diamond shape, and peer through, as one would in a camera’s viewfinder. Through the lens of a child, Roberts calls on the viewer to take responsibility—a responsibility to see Black children in earnest, expansively; to see the weight and also the joy of the many worlds that Black children may carry. As a parent, community member, bystander, or accomplice, our responsibility is to really see children. We must hold a child’s gaze as sacred, and act as such for the well-being of Black youth whose lives are too frequently put in jeopardy by a white-supremacist state.

In Little man, little man, six giant portraits of boys playfully dancing are pasted up on the surrounding walls of the Promenade Gallery. The mural installation references James Baldwin’s children’s book of the same name. In a video on the MCA Denver’s website produced by The Contemporary Austin—where an earlier rendition of the mural appeared—Roberts says “I love this idea of this boy standing there free, holding his hands up, asking for the world to pay attention, to stop, to pay attention to him; that he is important, that his life matters.” [3]

Two works from Deborah Roberts’ series Portraits: When they look back, 2020, mixed media collage on canvas, 45 x 35 inches each. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the MCA Denver.

For the series entitled Portraits: When they look back, Roberts features Black girls and uses black backgrounds—instead of white—to create their mixed media portraits. In these works, the girls’ bodies blend into the background almost completely, hiding in plain sight, with flashes of gold nail polish on their fingers and toes. Their faces, collaged in various shades, stand out in the wash of blackness. The gallery wall notes that “these works advance the artist’s long-time interrogation of colorism”. The message decoded is that Black girls must be treasured by our society, and yet they are largely hidden, almost nearly erased.

Stepping into the corridor between spaces on the second floor of the museum, you can hear the jazz piano from Jason Moran’s concurrent exhibition below. It’s a fitting soundtrack for Roberts’ Fighting all the ISM, towering above the viewer like a prophet. The title likely refers to the stem-word ism, as in racism. A child holds out both hands as if to push the viewer back—another beautifully depicted Black child, embodying their agency.

Deborah Roberts, What if?, 2020, mixed media installation, 84 x 96 x 48 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the MCA Denver.

The final room of the exhibition displays two booths that make up an audiovisual installation entitled What if?. Here, Roberts explores a new medium while keeping consistent with the themes of Black identity. Before entering the booths, the museum guards offer viewers disposable earbuds. In the first booth, patrons sit facing a full length mirror. The recording they hear, a Black man’s voice, blatantly sexualizes young Black girls. Following that is a white woman’s voice, judging Black women’s hair and lifestyles.

The next booth features a video in which the artist live collages with various materials: an African mask, paper cutouts, and money. While white women recite a list of Black women’s names, we see them transposed onto the collaged paper. The names of the women are written in cutout material on the walls, and there are shadows from the bars that enclose the top of the booth. Roberts’ What if? exposes patrons to an overwhelming synthesis of the cultural expectations of Black women, mimicking compounded traumas. Perhaps, what if Black women were liberated from these aggressions?

Two works from Deborah Roberts’ series Pluralism, 2020, silkscreen on paper, 30 x 22 inches each. In the background: Roberts’ Fighting all the ISM, 2019, mixed media collage on canvas, 72 x 60 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the MCA Denver.

Outside the installation booths, Roberts’ Pluralism provides space for grounding and continued exploration. The series features many variations of text printed on paper, such as Anqwenique is mild as milk. The black type is printed on white paper and “Anqwenique,” a Black woman’s name, is marked with a red line beneath it, denoting it as misspelled. Several printed variations of this common occurrence bring attention to the way that Black people and their names have been subjected to the white gaze, and labeled as “incorrect” through technology and otherwise. Pluralism caps off Roberts’ show with the same spirit of awareness and thoughtful protest seen throughout.

Roberts’ art encourages us to bring human dignity and freedom to the forefront of our daily lives, especially when it comes to the younger generation. As Roberts says, “The playfulness is there, but there’s medicine in there too”. [4] In I’m, it is our job as viewers to bear witness to Roberts’ playful medicine. The task is not to expect something more or something less of Black people, but to simply witness the unfolding of another world of Black experience so that we might come to see each other more deeply, and empathize with and protect each other.

Renée Marino (she/they) is a writer and multi-disciplinary artist residing on land stewarded for thousands of years by the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Ute people as well as at least 48 other Indigenous tribal nations. They are a board member of Street Wise Arts, a non-profit with a mural festival based in Boulder. They are an advocate for the arts, for social awareness, and for communal healing. In early 2021 their work was featured as a part of Shame Radiant in RedLine’s THREE ACTS: A Survey of Shame, Emotion, and Oblivion.

[1] Joshua Bennett, “I WILL NOT BE TAUGHT TO BEHAVE”, Art in America, May/June 2021 issue, pp. 96–99.

[2] Ibid.

[3] The video is available here: https://mcadenver.org/exhibitions/deborah-roberts-im/little-man.

[4] Bennett, “I WILL NOT BE TAUGHT TO BEHAVE”.