Pitit Tig / Children of Tigers

Pitit Tig / Children of Tigers

Leon Gallery

1112 E. 17th Avenue, Denver, CO 80218

January 15-February 26, 2022

Curated by Viktor El-Saieh

Admission: Free

Review by Renée Marino

On a wintry Sunday, I had the pleasure of walking through Leon Gallery with Viktor El-Saieh, the curator of Pitit Tig / Children of Tigers. Featuring works by ten contemporary Haitian artists, including El-Saieh himself, the exhibition tells many interweaving stories. Bright colors warm the air. Deities, mermaids, and townsfolk depicted as cats play out cultural rhythms through densely painted scenes, textiles, carved wood, and clay sculpture. The artists’ work speaks for itself—brilliant in technique, craft, and character. Most of the pieces were lovingly created thousands of miles away. Despite the distance, Pitit Tig / Children of Tigers is embedded with a reverence for Haitian culture, history, and spirituality that gives art patrons a glimpse into this faraway home.

The entry area of the exhibition Pitit Tig / Children of Tigers at Leon Gallery. On the left: Feret Charles, Untitled, 2022, textile, beads, and sequins, 66 x 76 inches. Image by Amanda Tipton Photography, courtesy of Leon Gallery.

At the entrance of the gallery, Feret Charles’ Untitled welcomes patrons with thousands of beads and sequins that have come to life. A swinging bat dangles from a wooden cross. A ghostly skeleton beats a drum. Coffins, bottles, bones, candles, and spiders all grace the scene—more than the eye can take in during one viewing. The variance in bead placement and type creates shading and texture in the flag’s many depictions. To create even one small candle the artist must have used over a hundred beads. El-Saieh explains that the technique employed in these flags is mostly seen elsewhere, in garmentry, and using the embellishments to produce expertly detailed imagery is quite unique.

A detail view of Feret Charles’s Untitled, 2022, textile, beads, and sequins, 66 x 76 inches. Image by Amanda Tipton Photography, courtesy of Leon Gallery.

Feret Charles is not the only textile artist in his family— his younger sister Wildane, and youngest brother Jacky, each created a Vodou flag featured in the exhibition as well. This unique art tradition has been passed through their lineage. El-Saieh explains that their mother, Myrlande Constant, is “the most famous Haitian textile artist of our time.” She was recently selected as one of three Haitian artists to be featured in the world-renowned International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. The Charles siblings being brought up by a modern legend speaks directly to the Haitian Proverb of which Pitit Tig / Children of Tigers is named:

Pitit Tig, Se Tig

The children of Tigers, are Tigers

The child of the Tiger, is a Tiger

A baby Tiger, is still a Tiger

Two views of Mme Moreau’s Dessalines, 2022, textile and beads, 26.75 x 22.25 inches. Images by Amanda Tipton Photography, courtesy of Leon Gallery.

In another fantastic work of textile art, Mme Moreau’s Dessalines, we see Haitian history represented. This vibrant beaded piece depicts Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the general who ultimately led the Haitian revolution to victory. Haiti’s liberty rests with the revolutionaries—Africans, enslaved by the French, who gave their lives fighting for freedom, not only from slavery but colonization as well. Decades before the U.S. instituted abolition, these revolutionaries had established the first Black republic. They dedicated the land back to its original inhabitants, naming it Haiti, which is derived from the indigenous Taíno word Aye-ti, meaning “land of mountains”.

Hugue Joseph, Two Mermaids, 2022, wood, 17 x 9 x 3 inches. Image by Amanda Tipton Photography, courtesy of Leon Gallery.

Hugue Joseph's Two Mermaids grace the foreroom beside a Vodou flag. These creatures call forth more of the mystique of Haiti. El-Saieh notes that mermaids are a mainstay of Haitian culture, and rightly so on a small island surrounded by warm Caribbean waters. I like to think the Two Mermaids locked in a kiss defy the gender binary. Beside the Vodou flag, it’s as if they echo the acceptance that Haitian Vodou exhibits for diverse gender and sexual identities. [1]

On the left: Viktor El-Saieh, Waterfall 1, 2022, ink on paper, 18.75 x 15.25 inches, and on the right: Herold Pierre-Louis, Portrait with Doves, 2022, acrylic on cardboard, 24.5 x 20.5 inches. Image by Amanda Tipton Photography, courtesy of Leon Gallery.

On a nearby wall Viktors El-Saieh’s drawings hang between works by Herold Pierre-Louis. They complement one another in illustrative splendor, while contrasting in style. El-Saieh’s drawings are smaller, but more full of characters and scenery, while Herold Pierre-Louis’ paintings have a refined sense of symbolic storytelling, both surreal in their own right.

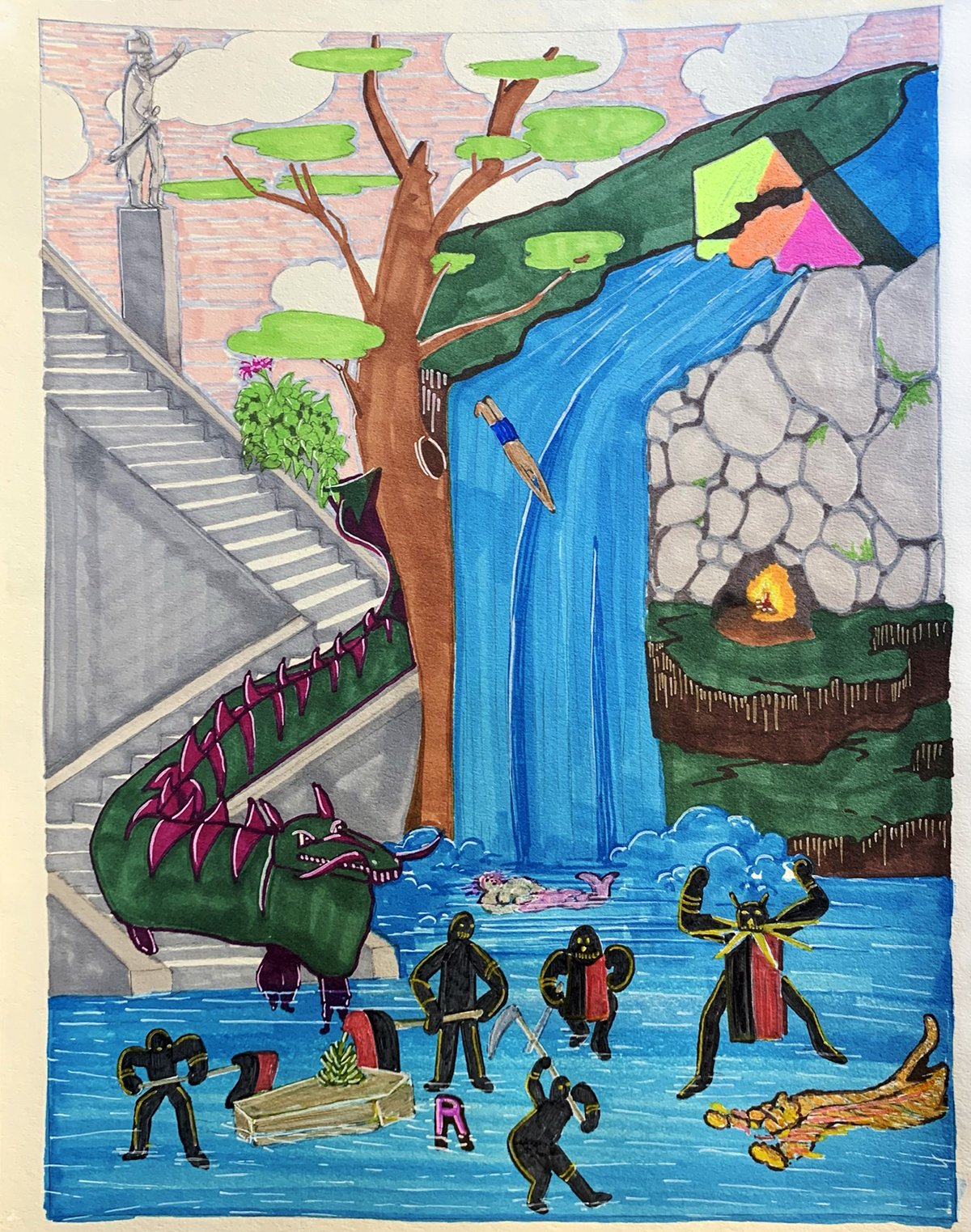

Viktor El-Saieh, Waterfall 1, 2022, ink on paper, 18.75 x 15.25 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Born in Port-au-Prince, El-Saieh grew up in Miami, Florida, and now resides in Denver. Like the Charles siblings, he is also connected to the Haitian art community by lineage. His parents own the El-Saieh gallery in Port-au-Prince, and his brother, Tomm El-Saieh, is an artist too. There’s a clear sense of inspiration in El Saieh’s work from his Haitian contemporaries like Herold Pierre-Louis. Pierre-Louis’ surrealist sensibilities have Haitian roots tracing back to artists such as Hector Hyppolite, a renowned Haitian artist and Vodou priest, born in 1894. [2]

Pierre Louis, Village Birth, 2022, painting on canvas, 30 x 20 inches. Image by Amanda Tipton Photography, courtesy of Leon Gallery.

It is apparent that Pierre Louis (a different artist from Herold Pierre-Louis) has honed his signature content: townspeople depicted as black, panther-like cats, in incredibly intricate and expansive scenes of Haitian life. Using these cats he playfully honors human nature. Village Birth is one of his show-stoppers. Under a moonlit sky, a crowd of cats surrounds a mother who’s just given birth and is still connected to her young by the umbilical cord. The fantastical style of Louis’ paintings, paired with their endless narratives, are simply hypnotic. One could imagine owning Beach Scene, Brothel, or Wedding, and finding new and interesting revelations in them each day.

Marithou, Seated Woman, 2022, ceramic, 12 x 6 x 10 inches. Image by Amanda Tipton Photography, courtesy of Leon Gallery.

Just beyond Village Birth sits Marithou’s Seated Woman, as if effortlessly minding the painting beside her. Marithou subtly depicts such a curvy, satisfied looking woman with reverence. The posture of the figure suggests that she is posing for no one's sake but her own. Seated Woman gives the sense that Haitian culture is one that values rest, specifically women’s rest.

Lissa Jeannot, Untitled, 2022, ceramic, 5.5 x 5.5 x 15 inches. Image by Amanda Tipton Photography, courtesy of Leon Gallery.

Another ceramic sculpture stands atop a pillar in the middle of the gallery. Lissa Jeannot’s Untitled begs pause for her powerful presence. She clutches an oversized machete, while the softness of her expression tells stories of sweetness; how protection and care go hand in hand. El-Saieh confesses that he hoped the figure would be the potomitan, or central pole of the exhibition, which in Haitian culture doubly refers to the matriarch of the family as well as the literal central pole in a Haitian Vodou temple.

An installation view of the exhibition Pitit Tig / Children of Tigers at Leon Gallery. Image by Amanda Tipton Photography, courtesy of Leon Gallery.

Early on in our walk-through, El-Saieh expressed that part of his intention for the show is “to answer the question of whether Haitian art has context here”. Pitit Tig / Children of Tigers is surely the question as well as an answer. El-Saieh has undoubtedly put in the work to create a context for Haitian art here in Denver at Leon Gallery, even making himself available for private tours twice a week to connect with the community. Through this time, he has gotten acquainted with several Haitians, proving the show to be a convening place for the Haitian diaspora in Denver. The art perhaps has even more significance in this new context, outside of Haiti, where there is less Haitian art and culture represented. There is value in new contexts and necessary representation, and I do hope that this introduction to contemporary Haitian art might one day have a reprise.

Renée Marino (she/they) is a writer and multi-disciplinary artist residing on land stewarded for thousands of years by the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Ute people as well as at least 48 other Indigenous tribal nations. They are a board member of Street Wise Arts, a non-profit with a mural festival based in Boulder. They are an advocate for the arts, for social awareness, and for communal healing. In early 2021 their work was featured as a part of Shame Radiant in RedLine’s THREE ACTS: A Survey of Shame, Emotion, and Oblivion.

[1] https://www.advocate.com/current-issue/2016/10/31/why-queer-haitians-are-turning-vodou

[2] https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-haitian-surrealists-history-forgot