Sinners, Saints & Fools

Maria Valentina Sheets: Sinners, Saints & Fools

Valkarie Gallery

445 S. Saulsbury Street, Lakewood, CO 80226

December 15, 2021-January 9, 2022

Admission: Free

Review by Maggie Sava

Encompassing 25 individual works and one large installation, Sinners, Saints & Fools—the exhibition currently illuminating the main gallery space of Valkarie Gallery—is the largest solo show of artist Maria Valentina Sheets’ stained glass art to date. The impressive display demonstrates her deep knowledge and appreciation for the material and the traditions of the genre. However, it also captures her impulse to experiment and expand the potential of the medium. Through a combination of complex portraiture and contemporary parables with not so simple answers, Sheets works to bridge the divide between the binaries of timely and timeless and worldly and unworldly, all while renegotiating social and cultural consecration.

An installation view of Maria Sheets’ exhibition Sinners, Saints & Fools at Valkarie Gallery. Image by Maggie Sava.

As Sheets describes it, stained glass is a component of her “genetic memory.” [1] She grew up in a Russian Orthodox Church which introduced her to religious art and her family owned a ceramic and art glass studio in Russia that ran for over a century. The familial and professional relationships she has with the material and medium, as well as her background in art conservation, are underscored in the care she imbues in the complicated construction of her art. [2]

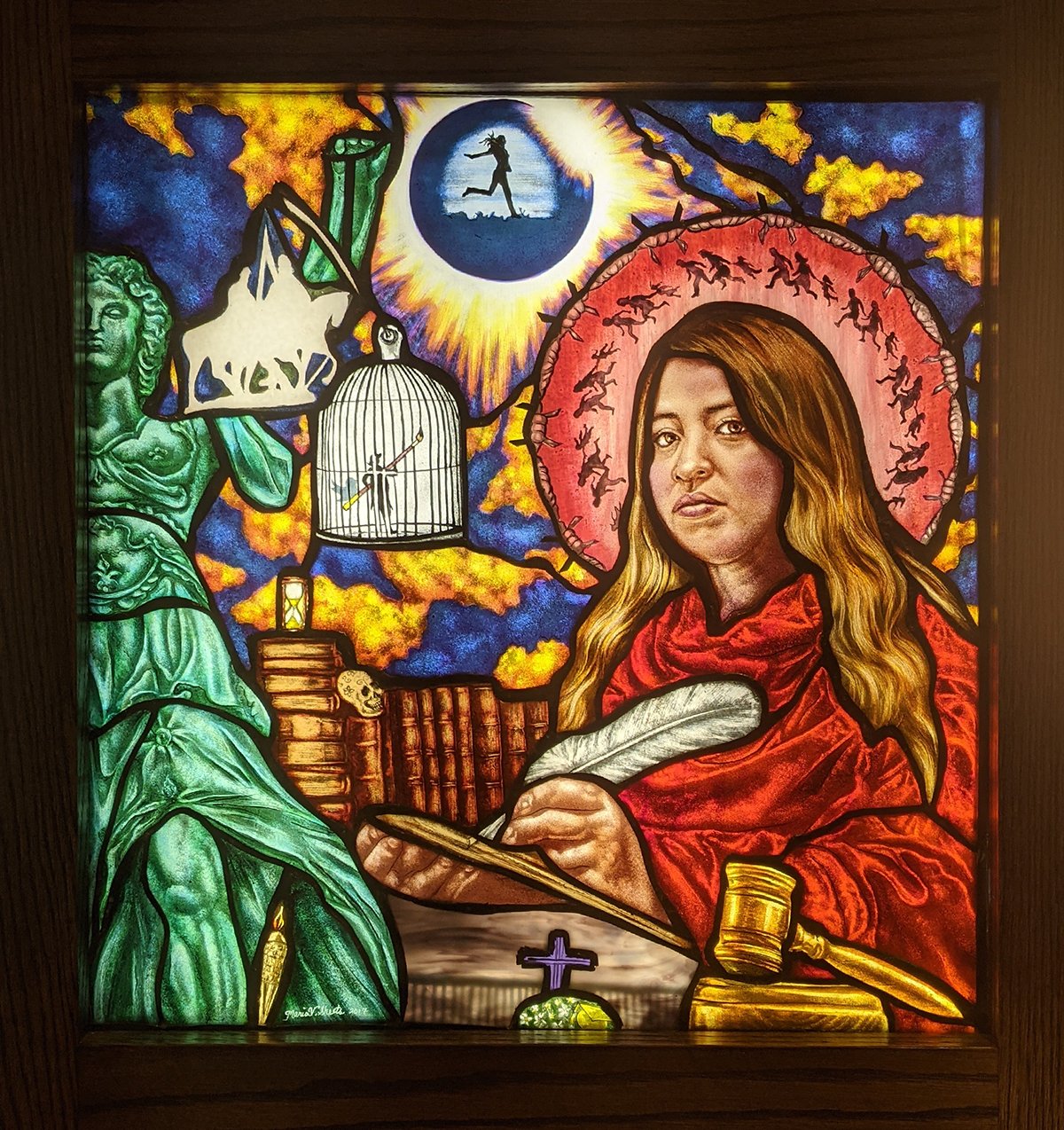

Maria Sheets, Wonderwoman, kiln-fired, painted stained glass, soldered, 52 x 27 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

Although building upon tradition, Sheets sets her work apart with her contemporary style and subject matter. Wonderwoman exemplifies Sheets' use of modern subjects and imagery, contrasting with the centuries old, traditionally religious nature of stained glass. In it, a woman tangled in her own lasso of truth lives among the trappings of a mundane life. Her suit is hung out to dry throughout the background of the scene, further distancing her from the fantastical elements of superheroes and the grandeur typically ascribed to this present-day type of saint. However, her home floats in among green cliffs, purple mountains, and a rising sun, giving it and the main character a sense of continuing transcendence despite how ordinary they seem at first. Hard to discern is which category Wonderwoman falls within—sinner, saint, or fool?

Maria Sheets, Saint Corona, kiln-fired, painted stained glass, soldered, 24 x 32 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Throughout the exhibition, Sheets’ deliberately modern recasting of saints creates a rich array of narrative imagery that prompts viewers to reflect on the pressing social issues the artist interweaves within them. For example, Saint Corona sets a young, blond woman against a profoundly relevant and recent landscape: the COVID-19 pandemic. She grasps the hand of someone just outside of the image’s frame and extends her other hand out to the viewer to continue the chain of human connection. Incorporating her contemporary sensibilities, Sheets creates an abstracted background that looks like tumultuous, cloudy, and colorful skies but really contains rubber gloves, toilet paper, and other artifacts of the global pandemic.

Maria Sheets, Great American Eclipse, kiln-fired, painted stained glass, soldered, 25 x 25 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

In Great American Eclipse, Sheets sanctifies the subject—an immigrant woman donning a halo outlined in barbed wire—while calling out the injustices hidden under the guise of supposedly just and impartial systems (that often criminalize immigrants and deny them access to opportunity, rights, services, and pathways to citizenship). [3] While performing social criticism, Great American Eclipse also imbues the saint with agency and strength. The woman gazes directly out to the viewer, asserting her deserved and legitimate presence, and in her hands she holds the quill and tablet upon which she will write her story. Above her, in the center of the sky, is an eclipsed sun indicating the absence of light—often the symbol of epiphany and progress. However, it holds in its center the image of a person leaping in the air, an indication of hope and alleviation which suggests that change may lay ahead.

Beyond her imagery, Sheets modernizes her work with forays into new techniques and technologies. This proves crucial in how the show builds a relationship to light, which is an essential element for traditional stained glass when it is in an architectural context. In this setting, the visual quality and vividness fluctuate throughout the day with changes in the sun’s position and brightness. [4] Without the natural animation that sunlight gives to the glass, Sheets creates an opportunity to experiment with alternative methods of creating progression and movement.

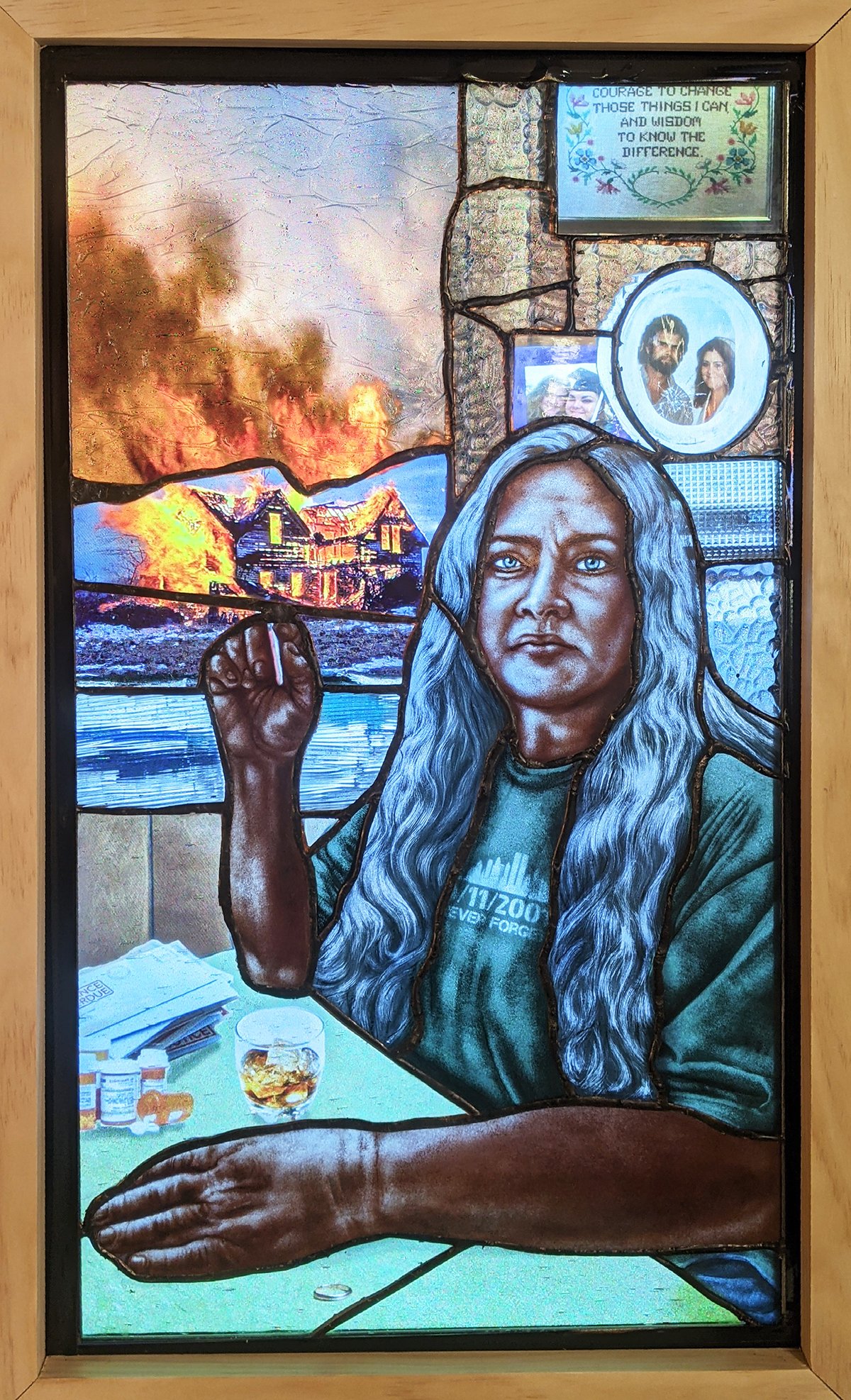

Maria Sheets, Last Cigarette, kiln-fired, painted stained glass, soldered over a Nimbus Frame with rotating images, 19 x 31 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

A detail view of Maria Sheets’ Last Cigarette, kiln-fired, painted stained glass, soldered over a Nimbus Frame with rotating images, 19 x 31 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

She plays out this experimentation in particular in Last Cigarette, a stained glass pane Sheets sets up in front of a Nimbus digital art frame. [5] The background, composed of rotating images on the screen, progresses through different stages of a woman’s life and provides visual details as clues of her circumstances and internal state at these distinct points of time. In one, her house is seen caught in flames in the background while on her table lies a glass of whiskey, pill bottles, and overdue bills—signs of a dark and tumultuous period in her life.

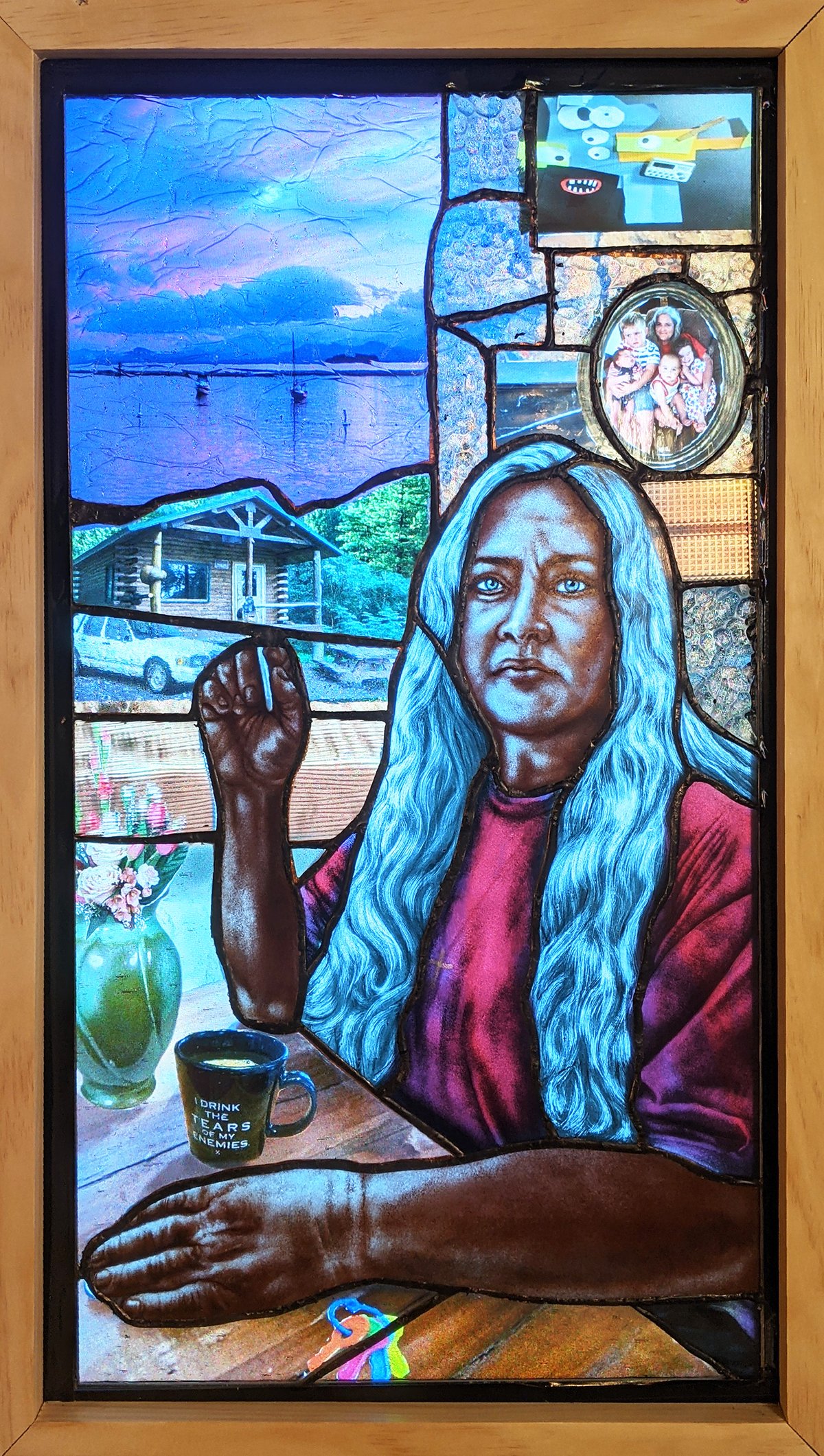

Maria Sheets, Last Cigarette, kiln-fired, painted stained glass, soldered over a Nimbus Frame with rotating images, 19 x 31 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

In another, a placid lake scene evokes a calm and happier moment, further evidenced by the vase of flowers on her table, the fact that she is drinking coffee instead of alcohol, and a picture of her and what appears to be her grandchildren hung on the wall behind her. This unique approach to visual storytelling and the relationship between the transparent nature of the glass and the shifting digital atmosphere in Last Cigarette showcases Sheets’s desire to continually innovate and expand her practice. As with Wonderwoman, the care she gives to her subject in Last Cigarette complicates her placement within the spectrum of sinner, saint, and fool.

What makes Sheets’s storytelling all the more impactful is her choice of model. As with Wonderwoman, Saint Corona, and Last Cigarette, most of the figures in Sheets’s works are modeled after people she knows. The details in her skilled realistic portraits personalize each character and make the thematic and allegorical content more relatable, for it feels connected to an individual’s life rather than an archetype.

Maria Sheets, Void Series, kiln-fired, painted stained glass with stands, 8 x 12 inches each. Image by Maggie Sava.

In direct opposition to this connection that Sheets’s forges with images of friends, family, and acquaintances, her installation VOID is made up of 33 celebrity faces. Unlike the other works, in which the subjects help convey Sheets’s message, VOID takes power away from its characters because, as Sheets states, “far too often we disown family and friends over the opinions of famous or powerful people we have never met or spoken to.” [6] Devoid of eyes and mouths, the visages are decontextualized from their famous bodies. Consequently, this draws more attention to their forms rather than their identities. The faces, formerly belonging to those given the status of social sainthood or special significance, are thus transformed into anonymity.

While Sinners, Saints & Fools takes up only one room, it contains a multitude of threads, symbols, and suggestions that the viewer could spend hours untangling and exploring. Yet Sheets does not abstract or hide her messages—there is a sense of visual accessibility throughout the show. And she does not shy away from challenging themes. Just as with scriptural stained glass, the compositional and aesthetic qualities of the works invite viewers to contemplate the stories contained within the art. Rather than spiritual meditation, however, Sheets prompts her viewers to embark on social, political, and interpersonal reflections connected to our histories and movements within the world. Separating herself from religious and institutional moralizings, Sheets takes back the power to decide who gets to be cast as a sinner, saint, or fool and what each role means in relation to the contemporary mythology the artist creates.

Maggie Sava (she/her) is a writer based in Denver, Colorado. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Art History and English, Creative Writing from the University of Denver and a master’s degree in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths, University of London. Writing is her main artistic engagement, which she pursues through research, art writing, and poetry.

[1] Maria Valentina Sheets, “About,” accessed 12/20/21, https://www.mariasheetsglassworks.com/about-mvs-glassworks.

[2] To learn more about how stained glass is made and assembled, see the video How was it made? Stained glass window shared on the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W5NOrG888CI. Sinners, Saints & Fools is itself a technical feat. Sheets constructed all of the frames and the LED boxes herself to light up her works and built the tables they rest upon, which is a clever method of display that emphasizes the sculptural quality of her stained glass.

[3] Sheets made Great American Eclipse for the Human Rights Initiative—a non-profit in Dallas, Texas which provides free legal and social services to immigrants and refugees—to tell the story of a client of theirs. Maria Sheets recounts this background information in her artist statement.

[4] The evolution of stained glass in the medieval period was intrinsically linked to architectural relationships to light and how much of it permeated the interior of churches. As such, when the construction of Gothic cathedrals allowed for more and larger windows, and thus more light, there was a surge in the development and construction of stained glass. Sowers, R. W.. "stained glass." Encyclopedia Britannica, June 11, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/art/stained-glass.

[5] Nimbus frames are electronic screens made to look like framed art that cycle through images and photographs selected and uploaded by the user.

[6] From Maria Sheets’s artist statement.