inVISIBLE | hyperVISIBLE

inVISIBLE | hyperVISIBLE

Dairy Arts Center

2590 Walnut Street, Boulder, CO 80302

May 20-July 16, 2022

Curators: Boram Jeong, Boyung Lee, Sammy Lee, and Chad Shomura

Admission: $5 Suggested Donation

Review by Renée Marino

inVISIBLE | hyperVISIBLE came to the Dairy Arts Center in Boulder near the end of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month and offers an incredible bounty of work from 16 different AAPI artists. The exhibition reaches beyond political and cultural bounds—a uniquely contemporary account of the lived experiences of a diverse demographic, with emotional depth and aesthetic playfulness in equal parts.

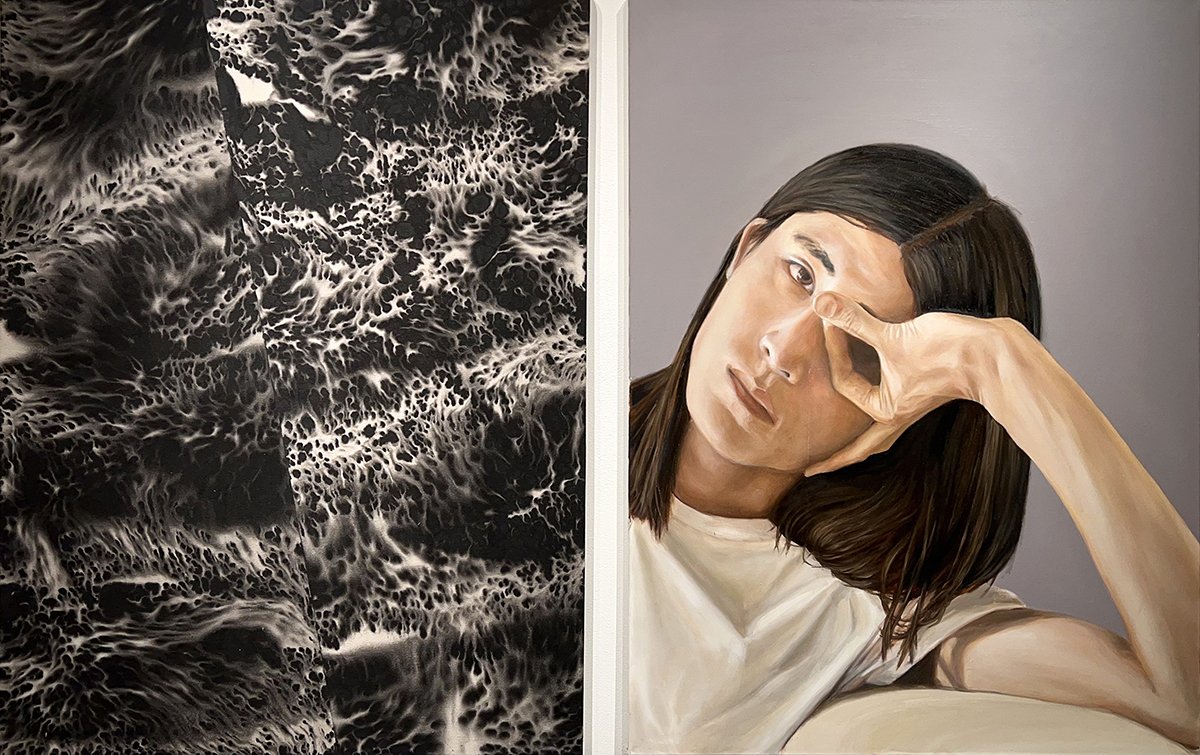

An installation view of inVISIBLE | hyperVISIBLE at the Dairy Arts Center. Image by Renée Marino.

In October of 2021, inVISIBLE | hyperVISIBLE premiered at RedLine Contemporary Art Center in Denver. One of the curators, Sammy Lee, remarks, “it was very lively and well-received, with inquiries to continue traveling the project”. [1] The latest installment at the Dairy Arts Center features additional artists who are local to Boulder. Included is everything from digital and screen-printed works, a short film, documentation of a guerilla art project, acrylic and oil on canvas, mixed media, and several large-scale installations.

Jennifer Ling Datchuk, American Flag, 2021, synthetic hair, porcelain beads from Jingdezhen, China, paracord, and collected affirmations, 60 x 30 x 3 inches. Image by Renée Marino.

Jennifer Ling Datchuk’s American Flag is a centerpiece in the exhibit. Datchuck presents a deconstructed American flag, thick with swaths of red and blue synthetic hair adorned with white porcelain beads. Collected affirmations are written on the white beads—a chorus of resilient messages urging us to keep living for a better tomorrow. Datchuk explains in her artist statement that despite the ratification of the 19th amendment in 1920, Asian-American, Native-American, and African-American women were still not allowed to vote until much later (African-American women were the last group to receive voting rights in 1965).

A detail view of Jennifer Ling Datchuk’s American Flag, 2021. Image by Renée Marino.

Datchuck pays homage to suffrage and discusses the tremendous inequality even amongst marginalized groups in America. She writes in her statement that the work of securing voting rights, even today, is “multigenerational, multicultural, intersectional, and absolutely necessary to dismantle power structures and build an equitable, inclusive United States.”

A detail view of Renluka Maharaj’s Neo-Dorado, 2021, mixed media on pigmented ink print, 40 x 60 inches. Image courtesy of Renée Marino.

Renluka Maharaj’s series Protectors of the Land continues the testament of oft untold experiences of Asian women of color by featuring striking, maximalist portraits of divine feminine beings of the Caribbean. In Neo-Dorado, the central figure is covered with a slick, black coating, bringing attention to extractivism—the extraction of natural resources from the earth.

Maharaj’s large-scale, multimedia works are innately empowering. Towering figures and lush colorful landscapes are also seen in Mama DeLo as well as Sita’s Resurrection. Small circular mirrors embellish the works, reflecting light onto the floors—all in participatory dance of art, earth, and woman.

Yikui (Coy) Gu, above: Just the Tip, 2017, charcoal, acrylic, colored pencil, marker, ink, fabric, photograph, aluminum foil, and fortune cookie fortune on bristol board, 19 x 24 inches; below: The Reach Around, 2017, charcoal, acrylic, silicone, plastic, coins, yarn, chopsticks, fabric, aluminum foil, and shotgun shell on bristol board, 19 x 24 inches. Image courtesy of the Dairy Center.

Yikui (Coy) Gu presents two collaged multimedia works in hypercolor: The Reach Around and Just the Tip. Both have an inviting, pop-art punchiness. A paper hand holds onto real chopsticks. The three central figures are all painted a bright yellow. Gu says in his artist statement on his website: “Through this combination of political, cultural, and domestic imagery, I hope to affirm and subvert the contemporary human condition through a Yellow lens.”

Joo Yeon Woo, Gyopo Portraits, Taekwondo Master, 2018, embossing on paper, 26.5 x 36 inches. Image by Renée Marino.

In contrast to Maharaj and Gu’s hypervisibility, Joo Yeon Woo’s Gyopo Portraits delve into the aesthetically invisible aspect of the show. These embossed paper relief prints can hardly be seen from afar, yet up close they are incredibly intricate. There is a felt sense of grief for what we could be missing—what is lost in the wash of whiteness? “Gyopo” means Korean emigrant. Woo’s portraits provide time-intensive, meaningful representations of the diverse lives of immigrants in her community, yet they also hold a sense of what can be lost in assimilation and marginalization.

Maryrose Cobarrubias Mendoza, If These Walls Could Talk, 2020, wallpaper, baseboard, and crown molding, 234 x 108 inches. Image by Renée Marino.

Maryrose Cobarrubias Mendoza’s If These Walls Could Talk is a wall-dressing, taking up the entire south gallery wall, and from afar seems to simply showcase a black and white baroque motif. However, upon close inspection, we discover that the images are actually a reclamation of racist sentiment from nineteenth century political cartoons. The cartoons depict the “savage” Filipino before imperialist expansion and the “civilized” Filipino after America's colonization of the Philippines.

A detail view of Maryrose Cobarrubias Mendoza’s If These Walls Could Talk. Image by Renée Marino.

Another motif on the wallpaper comes from the U.S. one-dollar bill, reminding us of America’s capitalist priorities. Ultimately the Philippines still faces the repercussions of nineteenth century colonialism today. The subject matter of If These Walls Could Talk is dark, yet Medoza’s work remains powerfully playful, starting necessary conversations right there on the wall.

Ren Light Pan, left: untitled (fire/fire), 2014, water, ink, and acrylic blend on canvas, 48 x 36 x .75 inches; right: self-portrait of an unseen woman, 2013, oil on canvas, 48 x 36 x .75 inches. Image by Renée Marino.

With a simple color palette and divine textures, Ren Light Pan’s paintings soothe a weary mind. self-portrait of an unseen woman showcases the artist’s gorgeously savvy realism. The painting brings self-awareness to light—a feeling of the subject (the artist) being seen. In contrast, untitled (fire/fire) shows an abstract reprieve. The textures garnered from painting with water reveal the amorphous and transforming nature of identity. These works were created before the artist came out as a trans woman. Both now give space for understanding the exploration of the artist's identity—a time before they were able to become self-identified in, as she puts it, ”the dark years that came before.”

Sammy Lee, FOB, Arrived, 2017, various sized suitcases, hanji (Korean mulberry paper), and acrylic varnish. Image by Renée Marino.

Sammy Lee repurposes travel cases into sculpture using Korean mulberry paper and acrylic varnish. Lee’s ongoing series, FOB, Arrived, conveys the loss and uncertainty of the immigrant experience through such mundane, yet intimate, objects. The owners of these suitcases are invisible, yet together the structures of these left-behind objects transform into something greater. Lee creates a community of objects, a pillar of what remains and also what is left behind through immigration.

Yong Soon Min, OVERSEAS / at sea, 2011, mixed media installation. Image by Renée Marino.

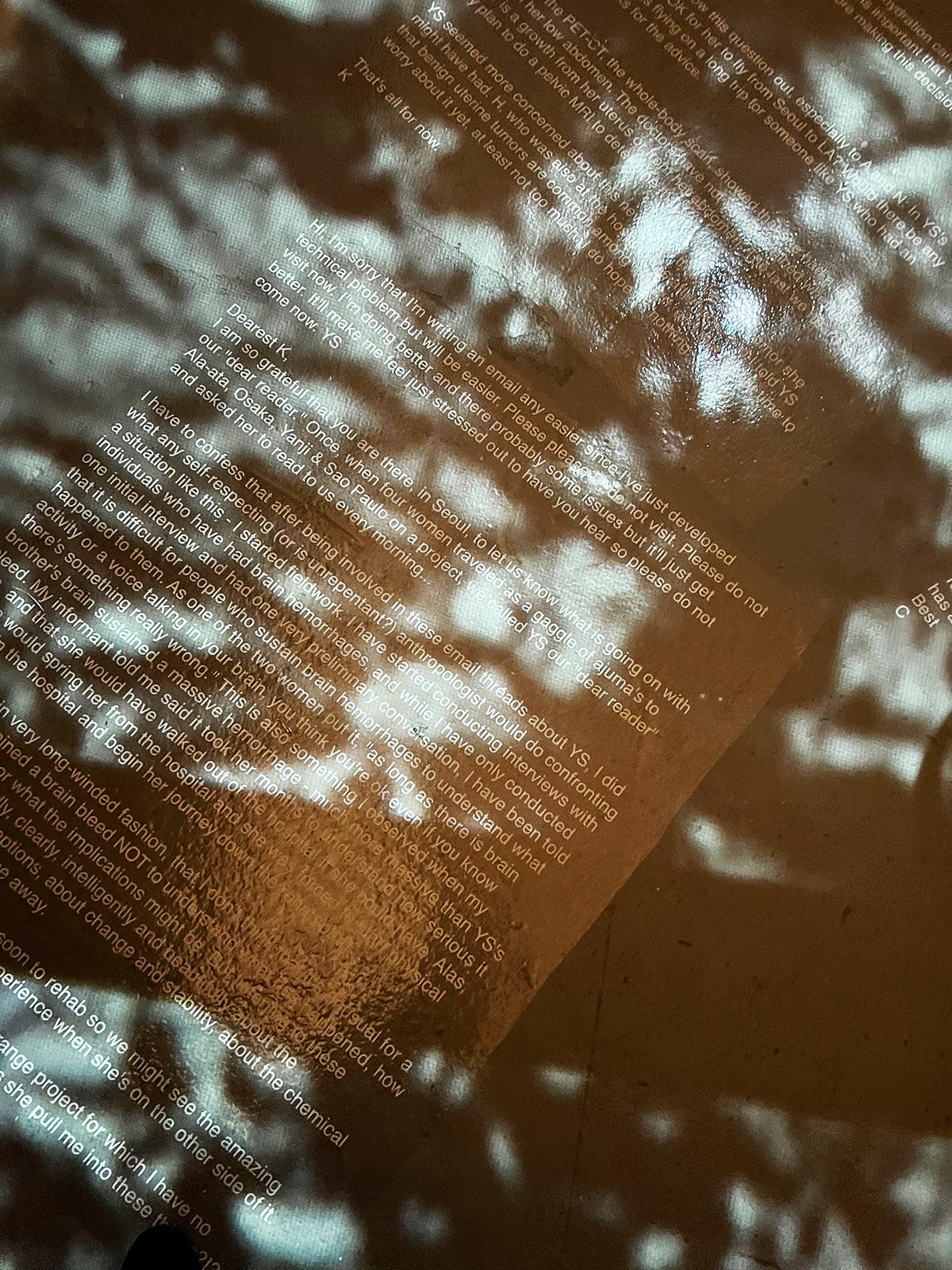

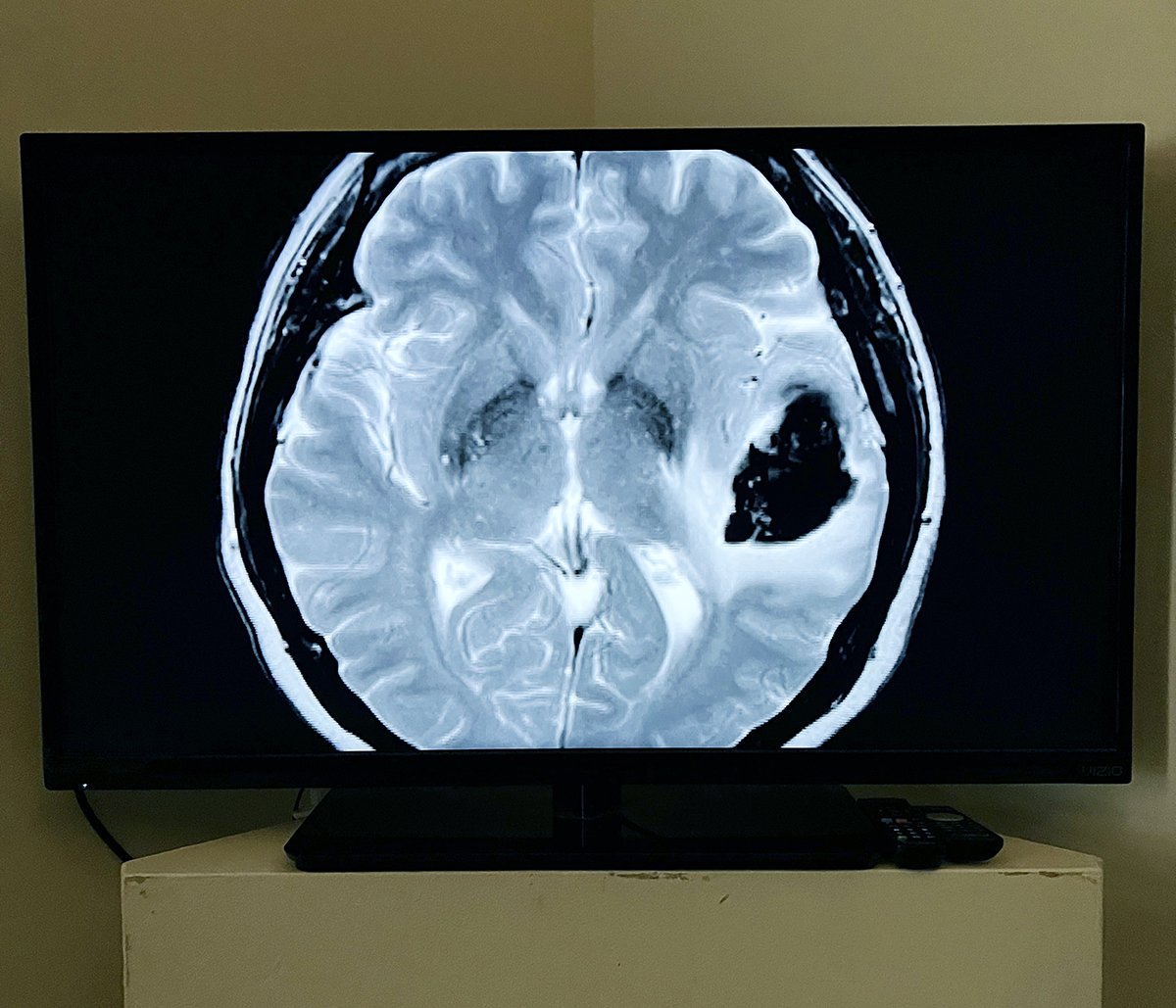

In her installation OVERSEAS / at sea, Yong Soon Min provides a space of tender contemplation. Email correspondences between the artist and friends in Seoul, Korea and the United States are printed on the floor behind a projection of liquid reflections. It is liminal and poetic—a romanticized space in between. Min’s healing experience post brain hemorrhage mingles with the broader themes of diasporic connection and disconnection.

Yong Soon Min, OVERSEAS / at sea, 2011, mixed media installation. Image by Renée Marino.

In a corner of the room, a video plays. Min uses imagery from her brain hemorrhage and many other moving images, often split in two. The voiceover fades between English and Korean: “Konglish.” A portion of the story of Alice in Wonderland is recited, in which Alice tries to make sense of her reality. Altogether the installation conveys a meaningful disorientation—whether it’s the distance between friends in an email, meshing together pieces of language, or exploring one’s own delicate existence.

Chinn Wang, Site 9, 2021, screen print on paper, 24 x 19 inches. Image by Renée Marino.

Chinn Wang presents five screen prints on paper, each a pixelated photograph with a central, completely blank tombstone. The print is black and white while colorful flowers surround the grave. These pieces make an immediate statement, but also leave room for continued exploration. Wang explains in her statement that she is concerned with the unique immigrant experience of erasure in both life and death.

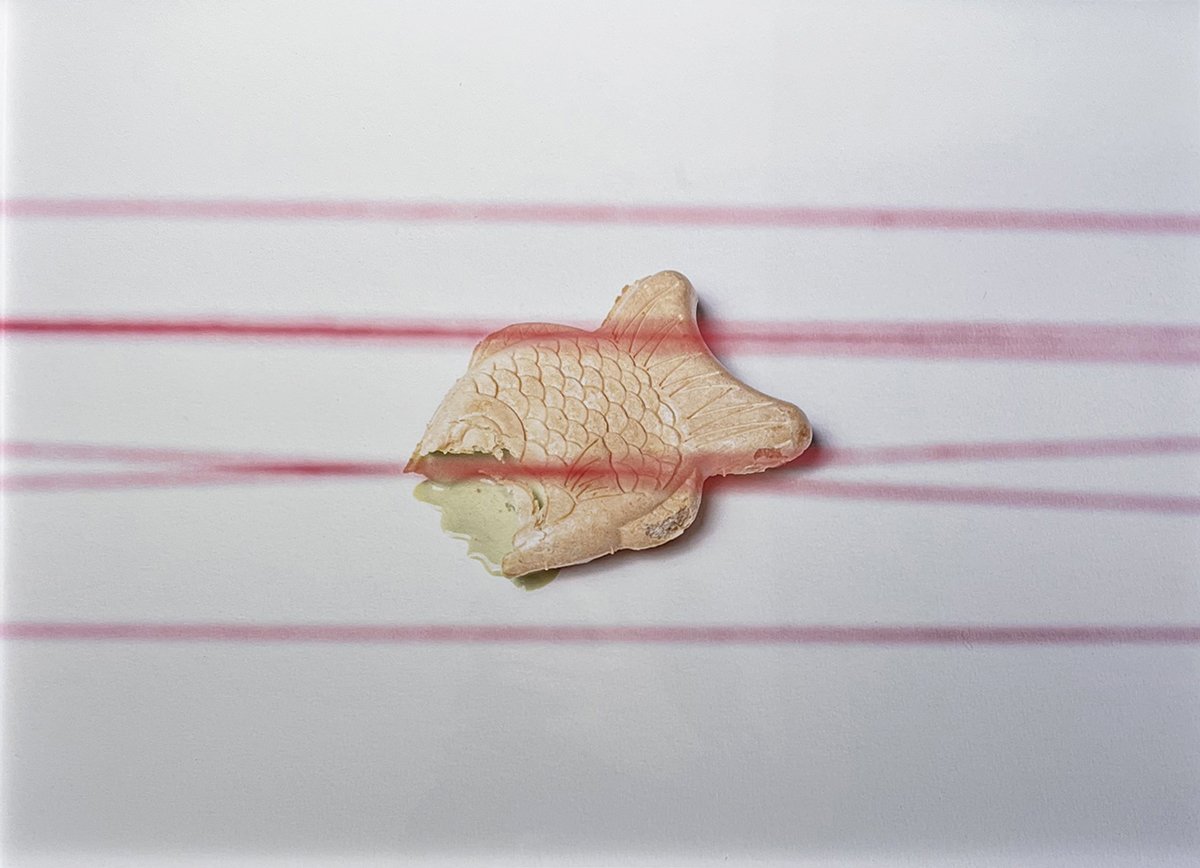

Thomas Yi, Fish Bread, 2022, digital pigment print, 12 x 16 inches. Image by Renée Marino.

Thomas Yi’s photographic series Pastime uses a combination of commonplace objects abstracted by red thread. The meaning of the series’ title is duplicitous. The red thread is a nod to the game cat’s cradle, a childhood pastime. As a second-generation immigrant, Yi also explores the quality of “intergenerational nostalgia.” In some of the photographs, the images are refracted as if taking on different viewpoints. With a meditative simplicity Yi allows common objects to take up more space in our mind’s eye, as he simultaneously makes space for his own authentic reflections on his place in generational time.

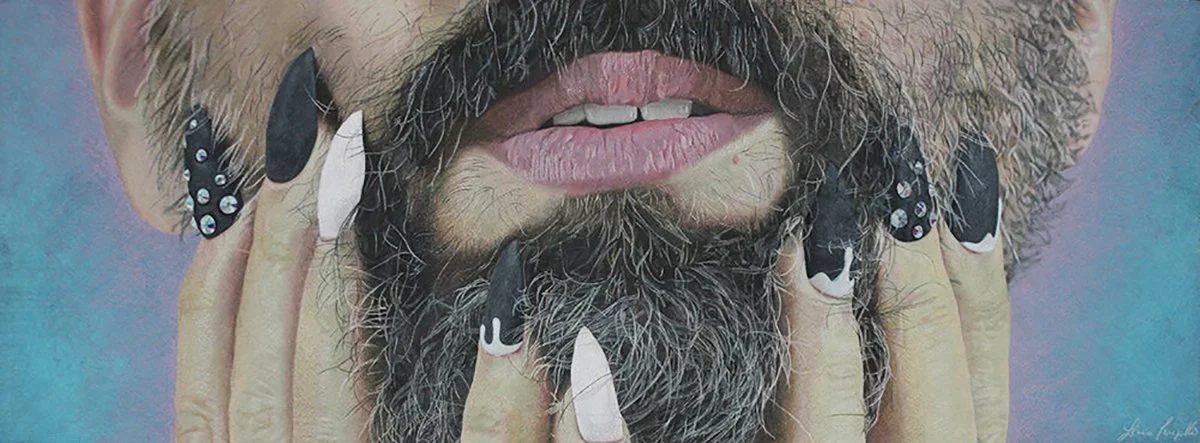

Jing Qin, Hand Manuscript II, 2022, oil on canvas, 28 x 36 inches. Image by Renée Marino.

Jing Qin displays three works in the show that all exhibit an enticing pop-culture surrealism. Hand Manuscript II features an alien-like hand form, appearing from the gold background, in a modern material-world smartphone moment. Qin’s style and choice in subject brings yet another dimension to such a wonderfully diverse group of artists in the AAPI diaspora.

A detail view of Liz Quan’s Dual Imprint, 2022, porcelain and wood, 23 inches in diameter. Image by Renée Marino.

Liz Quan, a local Boulder artist, explores her Chinese heritage through two porcelain and wood works entitled Dual Imprint. The wood, stained with red and blue varnish, and the white porcelain resemble the colors of the American flag. Atop each wooden disk rest entangled porcelain pieces imprinted with the designs of her own grandmother's embroidered silk collection. The porcelain shapes, like asemic writing, honor Chinese calligraphy. The two matching forms with negative space in the center evoke a sense of both oneness and separation, much like many AAPI peoples’ journey to embrace multiple identities at once.

A detail view of Tsogtsaikhan Mijid’s Motherland, 2020, fabric and polyester fiber, 39 x 24 x 32 inches. Image by Renée Marino.

Floating in the air, Tsogtsaikhan Mijid’s Motherland looks like something out of a Miyazaki animation. This plush, colorful fabric work seems to shapeshift at every angle. Mijid’s explanation of it is poetic and moving: “She is the submarine that travels on Earth, Sky and Water. She has the secret intuition eye. She is beautiful with psychic powers. She is the immigrant mother. When suffering comes, she transforms into whatever to save her offspring.” Mijid’s personified study evokes the imaginative art of resilience, necessary for survival and happiness, especially as one leaves home.

Erin Hyunhee Kang, The Mother Land, 2021, assorted photo and digital prints with acrylic on wood panel, 48 x 36 inches. Image by Renée Marino.

Boulder-based, first generation Korean American Erin Hyunhee Kang further explores ideas of maternal lineage and connection to homeland in her piece The Mother Land. The work has a contemporary yet traditional feel, harking back to wood block prints and landscapes. However, Kang uses modern printing techniques as well as somatic processes such as “exfoliating” the work, which she explains connects her to times as a child with her mother in the bath. On her website Kang further explains her practice: “While these fragmented spaces have become a specific container for my traumatic state of diaspora, they are still protected shelters where time stands still, where the presence of my existence can be felt, where I can build a future upon.”

Scott Tsuchitani, Memoirs of a Sansei Geisha: Snapshots of Cultural Resistance, 2004/2022, archival inkjet print (documentation of art intervention). Image by Renée Marino.

Scott Tsuchitani’s educational, artistic activism is a breath of fresh air. In 2004, Tsuchitani re-created a poster from the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, promoting the latest exhibit. The poster for the exhibit Geisha: Beyond the Painted Smile featured a model that was not even Japanese, much less a real geisha. Tsuchitani, a third-generation Japanese American, rebelliously superimposed his own face on the poster with the text “Orientalist Dream Come True” and “Perpetuating the Fetish.”

Then, he took his parody of the museum's ignorant portrayal to the streets. He hung posters and banners around the city, and even placed his own postcards on the museum’s visitor information booth. This critique and ongoing dialogue about the museum’s portrayal of Japanese women is a welcomed relief from the hypersexualization of Asian women primarily for the entertainment of white men. Tsuchitani notes that the project and the community's supportive response is “holding the museum to account and transforming racial discourse in the process.”

As someone who identifies with the vast AAPI community myself, there is a deep importance to seeing this level of representation in the gallery space. While some may perhaps be overcome with a felt sense of being “seen”—seeing themselves and their experiences represented—I was more-so excited by a great feeling of possibility. The multitude of diverse experiences contained in the AAPI experience ironically cannot be contained; for this, I am grateful. It is profoundly more liberating to be shown a portal to many unique worlds rather than a stiff directory for inclusion. The best thing we can do for one another, I believe, is to embrace our differences rather than reconcile them. New possibilities for the future are awakened in spaces like inVISIBLE | hyperVISIBLE, which makes room for appreciating differences through a compassionate, creative lens.

Renée Marino (she/they) is a writer and multi-disciplinary artist currently residing on land stewarded for thousands of years by the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Ute people as well as at least 48 other Indigenous tribal nations. They are an advocate for the arts, for social awareness, and for communal healing.

[1] From an email to DARIA from Sammy Lee on May 10, 2022.