Wood. Works & Three Pieces

Wood. Works & Carley Warren: Three Pieces

Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities

6901 North Wadsworth Boulevard, Arvada, Colorado 80003

January 21-April 25, 2021

Admission: free, but pre-registration is required.

Review by Mary Voelz Chandler

In 2017, the Arvada Center hosted a large exhibition titled Paper. Works. Paper? We all have paper, and usually too much of it, but visiting that immense display opened my eyes. A notable amount of beauty was on the walls, and there was a huge variety of art.

Now, we have Wood. Works, also at the Arvada Center. We know about wood. You can burn it in a fireplace, you can build a table, you can make a puzzle, and builders now have found a way to use treated timber in skyscrapers.

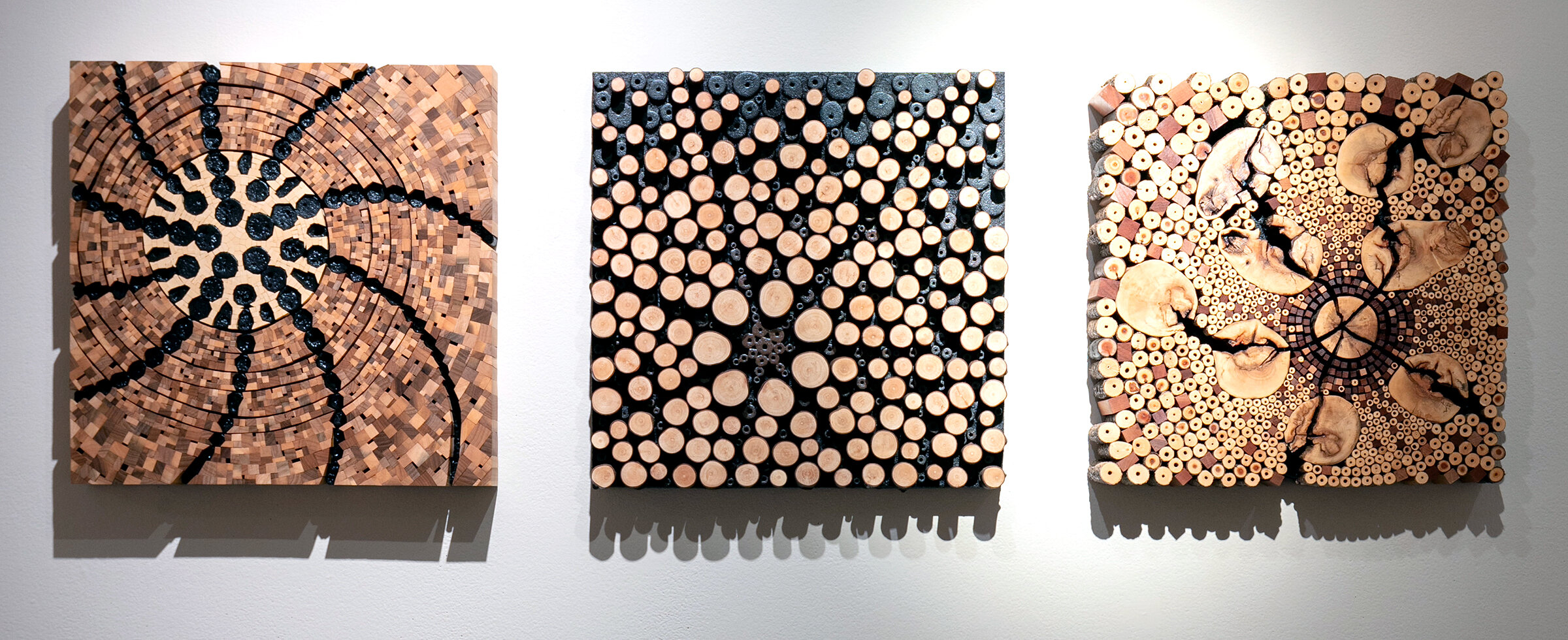

Wood. Works is all about allure and diversity. It is accompanied by another exhibition in the Theatre Gallery—Carley Warren: Three Pieces—that focuses on new sculptures by a well-known artist who works in wood.

An installation view of the group exhibition Wood. Works at the Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the Arvada Center.

Wood. Works features 24 artists with works spread out on both gallery levels. It’s like a travelogue: big and small, serious and humorous (and even sly), and oiled wood or rough wood or painted wood. But all of the works approach how artists are attracted to this fairly humble and mainly renewable material. Beetle-kill pine, the sad scourge of Colorado, has provided a helping handful of material, while exotic hardwoods are quite more luxurious.

Even before a visitor views the exhibitions, a piece by Scottie Burgess sits in the entryway inside the Arvada Center’s front doors. It looks like immense pears covered with rows of wood shingles painted black, and the stems at the top swathed in gold. Burgess titled his work Veneration of Wood—which is exactly what these exhibitions are about.

Leo Franco, Gathering, 2018-2020, exotic hardwoods. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the Arvada Center.

Entering the first-floor gallery, the space welcomes viewers with shapes that reflect the human form. Norman Epp’s eight abstract statues appear as if they are relating with each other. In Epp’s Time Rebirthing, made of walnut and steel, it seems that something is about to emerge from a fork between two branches; it is elegant and sensual. Along the right wall is Gathering, created by Leo Franco, a collection of 15 small totems made of exotic hardwoods. It looks like a reunion. To the left, Michael Beitz’s Family Tree, made with carved wooden heads that whirl around as if they were speaking to each other at a dinner table. The elements are painted a dark silvery gray.

Chris DeKnikker, And Again, 2000, poplar, holly, sunflower, sawdust, and pigment; Stargazer, 2000, maple, forsythia, sawdust, and pigment; and Beginning First Floor, 2000, maple, cherry, redwood, and forsythia. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the Arvada Center.

After that, you’re almost on your own. But if you veer to the left, there is a selection of artists who have created works that have the feel of a puzzle. Chris DeKnikker’s works includes three squares with tube-like elements that reflect elongated starfish, and another triad, free-form set of wooden pieces that include fissures and infills. His materials are holly, peach, mahogany, poplar, forsythia, and elm—and their colors are striking.

Then, a series of wall pieces include work by Mark Bueno, with wood that appears as if it were transformed into puzzles or quilts tightly joined together. Deborah Jang’s assemblages bring out a smile, with titles such as Shuttered In (including old shutters) and Building Sturdy Children (with toys and whimsy). Autumn T. Thomas’ works are elegant; the wood is curved with thin slices cut out. She also has a show-stopper titled Dark Side of the Moon, a crescent in wood and copper elevated on a thin column. Corey Dreith’s pieces read like small minimalist paintings that viewers can focus on their introspection. Andrew Lesuer sculpted wall hangings that stretch geometry, with Mandala and Gyre (he also has two, three-dimensional works on the second floor).

Sean O’Meallie, Dream Fruit of Psychedelic Produce, 2020, painted basswood. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the Arvada Center.

But before turning the corner to walk down the other side of the gallery, it is imperative to study Jerry Wingren’s four wooden carvings, especially a stand-out in red cedar titled Swallow Hill Totem. It is sleek and flowing, as if a bird were gliding above. Across from the left wall is a selection of playful works by Sean O’Meallie, who has lifted our spirits for many years. His Dream Fruit of Psychedelic Produce includes numerous polychrome wood pieces in soft colors and unusual definitions of these offbeat bits of produce.

Kim Ferrer crafted reclaimed and rough wood sculptures with little surprises in the center, including unfired porcelain and bronze. Nearby, Lauri Lynnxe Murphy’s niche in a side wall is filled with several dozen tiny pieces titled Community, incorporating beetle-kill wood, vintage paper, gouache, pins, and glass beads. This multi-piece collection is paired with four elongated beetle-kill wood planks covered with encaustic and other small items, pulling everything together.

Patrick Marold, Forest Floor, 2021, trees and branches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the Arvada Center.

The Center’s round gallery happily accommodates Patrick Marold’s towering (mini) forest. Forest Floor describes a ring of about two dozen beetle-kill logs stretching above to the window on the second-floor gallery. A few branches are placed carefully among the trees. Looking out the window on the second floor it is a reminder of the damages caused by wildfires during the 2020 events that destroyed so many trees, homes, and wildlife. Marold’s installation is evocative.

On the second floor, there are some smaller pieces with intriguing concepts. At the entrance Anne Shutan’s vertical sculpture is posted, which is titled Wooden Flame and made of mahogany. (Shutan has several more pieces toward the back of the gallery, including a sleek horizontal piece titled Purple Haze.) On the flip side of that wall, Brett Foxwell’s stop-motion video, Wood Swimmer, focuses on branches and wood. (Note: Foxwell lives in California and is the only artist in Wood. Works not living in Colorado.) Wood Swimmer is hypnotic, and you can’t not watch it.

Eileen Roscina, Shelter, 2021, willow and lightbulb. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the Arvada Center.

Nearby is a tall, bulbous sculpture woven in willow by Eileen Roscina, which projects an out-sized human form. It is titled Shelter for a reason: a light bulb is shining inside the sculpture, keeping something warm. A realistic clutch of wooden sculptures was created by Jaime Molina. He is known for creating murals, while working with another muralist, Pedro Barrios. Here, Molina carved and painted with vivid imagery: cactuses, a cactus sheltering a skeleton riding a bicycle, and a figure titled That Doofy Soul, whose hair (and beard) are made out of hundreds of nail heads. Molina has created many of these nail heads, called “cuttys.”

Anne Bossart has turned pieces of wood into paintings, with unexpected objects, hand-dyed and hand-woven cotton, and in one case a band saw blade positioned as if it were its inner frame. Bossart’s Riitta is a star turn.

Kazu Oba has traditionally worked in ceramics, but here he has turned to wood. (As a side note, he apprenticed with two masters: Jerry Wingren, who has works downstairs, and Takashi Nakazato, a renowned potter in one of the ceramic centers of Japan). Oba’s works are sleek, undulating, and some incorporate a tinted plaster or concrete and resin.

Two artists toward the back of the gallery have pieces on facing walls, allowing comparisons and observation of differences. Christine Dawson works in tracery, including Lakshmi, which is comprised of layered laser-cut oak and birch over plywood, displaying variance of color within stacks of wood. Across the aisle, Katy Casper also works in layers, in wood and acrylic in bright colors that add to the upbeat nature of her pieces.

At the very back of the gallery, Daniel Crosier created a wall hanging titled Inkdrop, which looks like a quilt but is made of patches of wood. It’s as if Crosier’s work put a punctuation mark at the end of the gallery, calling things to a close.

But: not quite yet.

A view of Carley Warren’s exhibition Three Pieces. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the Arvada Center.

In the Theatre Gallery, Carley Warren’s Three Pieces exhibition shows how many ways an artist can create numerous works with just three little pieces. They are cut in specific angles, over and over again. Even without a tape measure, one can tell that each of these little pieces are 4- or 5-inches long, and perhaps a square inch around on each side.

Warren’s sculpture has been on display at local galleries for many years—including Artyard, which has since closed. She moved to Colorado in the 1950s and earned a BA from Metropolitan State University in Denver in the 1970s (that is its name now). She began to create sculptures in acrylic plastic, but then moved to creating work in wood. This material has been her lodestar, and the artist’s statement from a different gallery notes this:

“My work represents a continuing interest in materials and craftsmanship. The nature of materials contain and suggest ideas to which each of us responds differently. It is my intention to use materials with careful attention to their inherent properties with the end result being respectful, but with a very different purpose. The materials used are from processed and manufactured goods, with an emphasis on wood. These I have manipulated to make objects that relate to the organic world. Part of the irony is in taking processed materials, changing the shape, using joinery, knotting, and other techniques, I’m turning them back into structures alluding to nature.”

The Arvada Center has explained that “This series was developed by Warren’s specific set of self-imposed rules: Warren uses only three consistent, wooden shapes, and each connection between the pieces is made at a straight angle.”

And this is true, as there are 23 sculptures which each are different: some are straight, some are curved, some are vertical, and some are horizontal. But Warren has stuck to her self-imposed rules, and it is up to viewers to understand them.

Carley Warren, Life Work, Then Spiders, 2008, wood and twine. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the Arvada Center.

The installation of Warren’s work is impressive, and the lighting casts shadows that bring out the best in these pieces. Conference is an ensemble of five statuesque pieces. In Life Work, Then Spiders, again shadows reinforce the diagonal image. And with Oversight, she has given this work balance, with two floral clusters of those “three pieces” from worlds apart on a staff. Warren also adds little pouches made of twine in some works, inserting another material she has used for years.

Over several decades, Warren has honored her material, elevating what some might call humble, but her attention and invention has exalted wood.

Mary Voelz Chandler writes about visual arts, architecture, and preservation, including in the position of art and architecture writer at the former Rocky Mountain News in Denver. She completed two editions of the Guide to Denver Architecture and was a co-author on the 2009 book Colorado Abstract, with Westword critic, author and historian Michael Paglia. Along with numerous awards for her writing, Chandler was honored by the Denver Art Museum in 2012 with the Contemporary Alliance “Key” Award, and received the AIA Colorado 2005 award for Contribution to the Built Environment by a Non-Architect.