Alejandra Abad

Artist Profile: Alejandra Abad

Taking Art Out of The Exhibition Space and Into Her Communities

By Jillian Blackwell

If an artist makes art and a pandemic keeps us all in our houses away from exhibition spaces, can the art still make an impact? Alejandra Abad has been answering that question in an innovative and resounding fashion. Since well before the pandemic, she has been making art for the people—art that explores and explodes the traditional boundaries of art world spaces. Her art derives meaning from its interaction with and amplification of the voices of underrepresented groups of people.

Abad is an MFA candidate in Interdisciplinary Media Arts Practices at the University of Colorado Boulder. Even at an early age, her interactions with others helped forge her identity as an artist. She says, “[g]rowing up in Venezuela, I was the kid that would help others draw, solve problems or make things out of whatever was available. [...] my peers named me an artist.” Her Venezuelan identity is important to her work. “I am a first generation immigrant born in Caracas, Venezuela, and my work gives agency to that identity. The ongoing corruption in Venezuela has prepared me to look at what is happening with other authoritarian movements around the world, and how I can comment on that as an artist.”

Not only does place help her find subject matter, it also supplies her with a visual and cultural language to express that subject matter. “I frequently draw on Venezuelan folklore and childhood memories, and even use materials and techniques that both relate to my upbringing and engage in the pluralism and multiculturalism of our contemporary world. I create honest and symbolic narratives in a visual language that depicts fragmentation, mythology, and folklore.”

A view of Alejandra Abad’s Guri, 2020, a pop-up installation with two channel video projections onto textiles, mirrors submerged in water, and a 5-gallon water jug holding one of the projectors with wooded dowels. Image courtesy of Alejandra Abad.

One example of her mixture of personal narrative and political critique is Abad’s installation Guri from 2020, which explores the subject of the Guri Dam in Venezuela. Found footage of the making of the dam is projected alongside a video conversation between her and her mother discussing current power outages in Venezuela and foreign exploitation of Venezuela’s resources. This piece critiques the Venezuelan government’s corruption and mismanagement of resources, foreign interference motivated by greed, and the lack of care for the Venezuelan populace. Although the work deals in weighty and, in the hands of a less talented artist, potentially impersonal issues, Abad grounds the work using the personal dialogue with her mother to speak to a larger cultural problem.

Her identity as an immigrant is also highly important in her art. “Being born in a different country and hearing the current narrative of how immigrants are seen [in the U.S.] is an awful, gut-wrenching feeling” she says. “I was moved to different spaces, I was given the opportunity to see how there are different margins and invisible borders that give people access and entry; human rights shouldn’t depend on nationality or citizenship, but that is unfortunately the case.”

She is the only child in her family who was not born with U.S. citizenship. “This played a huge role in my identity. I was detained as a child at immigration because my grandfather didn't speak English and I wasn’t travelling with my parents. That was a terrifying experience. The amount of prejudice that there is, and that we can see as children, is unbelievable. Later in high school I obtained my citizenship. However, I always remember that moment and I always think about how others feel. My artwork is deeply affected by place and what it means to have lived in different landscapes, and imaginary divisions that we create to separate groups of humans from one another.”

Place, personal narrative, and politics are inextricably linked for Abad, for whom, “all art is political.” Through collaboration with her communities, she “explores how we can occupy spaces where people are often told that they don’t belong, and [creates] new spaces for all people to have a sense of belonging in creative communities.”

Alejandra Abad’s original image for her Giant Coloring Book project proposal at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Miami. Image courtesy of Alejandra Abad.

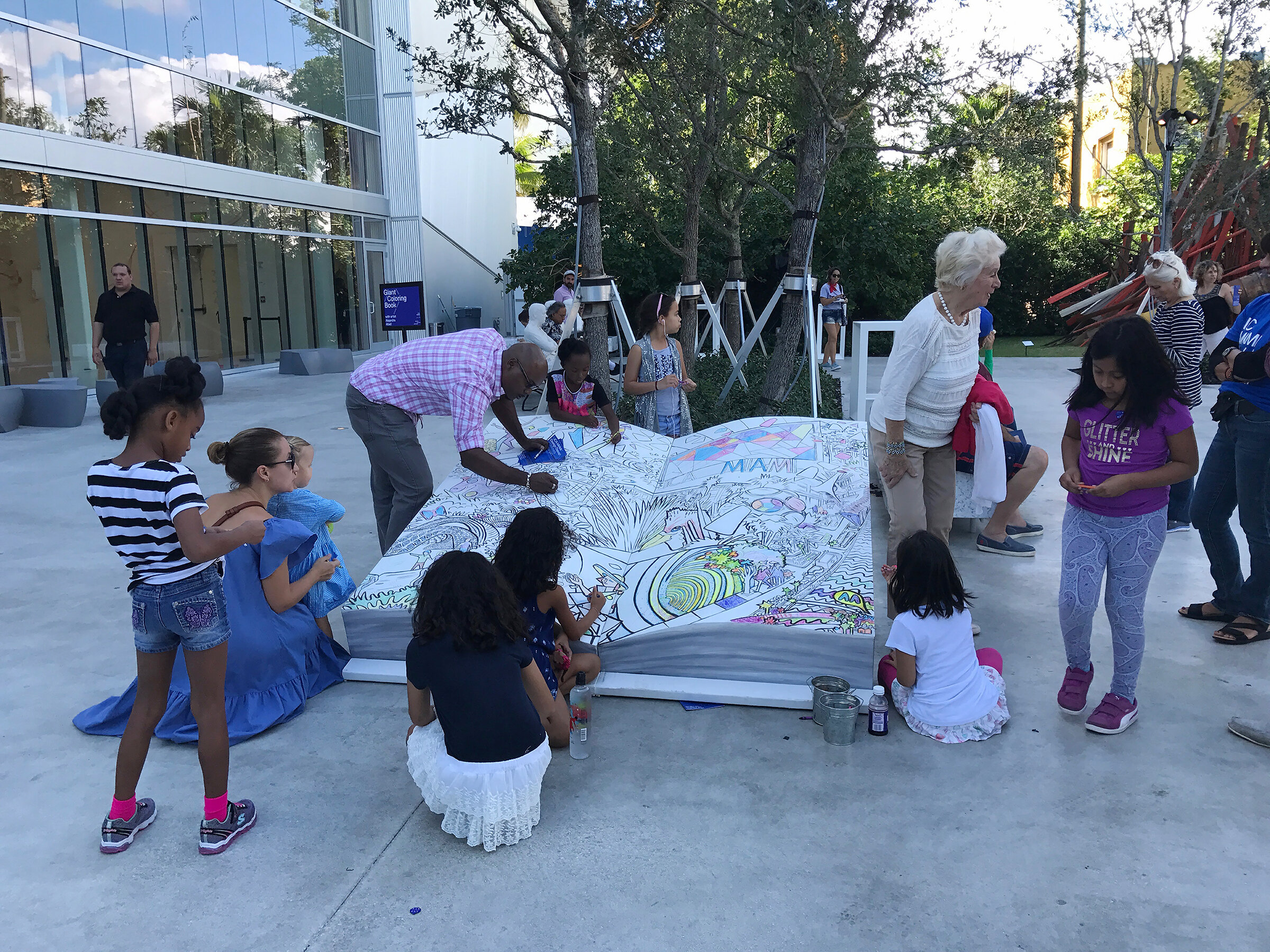

Visitors at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Miami coloring in Alejandra Abad’s Giant Coloring Book, 2017, painted wood and paper sculpture. Image courtesy of Alejandra Abad.

When working with communities, uplift is her goal. Abad asserts that the role of an artist should be “to find ways to collaborate and partner with communities, to work with people of different identity categories in solidarity for the greater good, by empowering others and providing skills that can uplift one another.” In 2017, Abad created the Giant Coloring Book, “as a tactile outdoor installation” for the Institute of Contemporary Art in Miami. [1] All were welcome to color in its pages, creating an “end result [that] was determined by community participation.” This playful piece has the underlying mission of drawing community together and breaking down the barriers between art institutions and people.

Abad’s most recent community art project, Unidos Club, is a collaboration between her and fellow CU student Román Anaya. Abad and Anaya collected messages of hope from the community through an online submission form on their website, Unidos.club, which is written in both English and Spanish. They then transcribed these messages onto colorful flags that were displayed in such places as the Santa Fe Arts District in Denver (January 15-February 15, 2021) and One Boulder Plaza in Boulder (February 1-28, 2021). Abad and Anaya aim to reflect the community’s hopes back to them, so that people can experience art that speaks directly to them with their own voices. Abad describes it as “a project that is centered around wellness [that] is really helpful because it challenges us at a very difficult time, with both a pandemic and a divided populace, to be hopeful for the future.”

Román Anaya (left) and Alejandra Abad (right), wrapped in the textiles they created for their 2021 Nuestros Deseos/Our Wishes project under the collective name Unidos Club. Image courtesy of Alejandra Abad.

“Our dream is that we can support and influence each other and our communities to combat racism, xenophobia, and violations of human rights. Giving children and families an opportunity to be part of the conversation is a major goal in all of our work. This is an anti-racist practice, to lift others up when far-right movements are trying to demoralize our communities. We all know which communities are hit the hardest during the pandemic, and yet our leaders have not acted. We, however, have a platform as graduate art students, and we want to use it to amplify underrepresented voices. By positioning ourselves in public spaces where marginalized groups are often discouraged from participation, we can create [a] passage for more opportunities for future generations. Art might not always have a space in the lives of adults and children in working families, in large part because of a lack of access to these opportunities or privileges. If Román and I occupy spaces where people like us are often missing, then we are shifting the culture.”

Alejandra Abad placing text on the banners for Nuestros Deseos/Our Wishes. Image courtesy of Alejandra Abad.

The Unidos Club project is incredibly tender, summarizing the feelings of many through the specific and heart-rending hopes of individuals. Abad comments, “Yeah, some messages have made me cry. [...] I saw a message that read ‘I wish grandfather gets better.’ It shook me, we are up to nearly 400,000 COVID-19 deaths, and I have gotten many messages that are related to this.” [2] With the future unclear and evictions occurring and imminent, one message that sticks out to Abad is “I wish in the future we had housing within the financial reach for all.” For Abad, catharsis is paramount. “Being vulnerable with others allows us to represent our messages to a larger public, which can lead to collective well-being.”

Unidos Club (Alejandra Abad, Román Anaya, and the public), Nuestros Deseos/Our Wishes, 2021, outdoor textile installation at the Museo de las Americas on Santa Fe Drive in Denver. Image courtesy of Alejandra Abad.

Abad shares an anecdote about the installation of the flags on Santa Fe Drive: “I recently installed a flag in the Denver Art District on Santa Fe Drive and a guy in a truck pulled over with his window open and yelled, ‘Hey thank you for these messages! We really need them now.’ At first I was scared, because of what has been happening in the news and all the bigotry directed at immigrants, but this interaction helped to restore my hope and faith that we got this, that we want unity, that there is public agency in collaboration. We need to reclaim spaces and celebrate each other’s self expression.”

A banner from Nuestros Deseos/Our Wishes that translates to “I Wish The Sick Were Healed, On Their Feet And Moving Forward!” Image courtesy of Alejandra Abad.

Being an artist and activist are not two separate identities for Abad, but one and the same. “What do we want to foster as artists? Do we want meaningful change? Are we just promoting self-expression, or do we also value empathy and critical thinking? What kind of representation are we asking from museums and organizations? What do we need to change to combat systemic racism? All of this is tied to the role of an artist, whether artists overtly consider these issues or not. These issues also apply to others with power in the art world. Who are they curating? Who are they opening doors to? Who do they allow in their circles? We are all ambassadors of what we cultivate.” These are piercing questions for our time and lack simple answers. However, Abad’s art suggests that there are satisfying responses that exist at the intersection of art, community, and political awareness.

With these sentiments in mind, Abad looks forward to future projects. In April, she will be part of an exhibition at Union Hall in Denver entitled Object Empathy, alongside Colorado-based artists Marco Cousins and Daniel Granitto. [3] In the summer, she will travel to Florida to install a solo show at the Pompano Cultural Center. It will “include animations and projections onto sculptural elements,” and will “all relate to myths and ideas of Venezuelan identity, cultivating and reimagining how these narratives relate to a hybrid immigrant identity.”

Alejandra Abad has an ethical vision of her role as an artist. “I believe art and ethics are good friends,” she states. She hopes to “heal and not harm,” for she sees art as a potential salve for her communities. “[W]e don’t have the answers to solve every problem, but I do think that we need to focus on what we can contribute to the greater good if we want to see change. We can all do a little bit of that. We need to be aware of what we take, and how we can give back.”

Jillian Blackwell is a Denver-based artist and art educator. She holds a BA in Fine Arts with a Concentration in Ceramics from the University of Pennsylvania.

[1] https://alejandraabad.com/project/our-place-in-the-miami-design-district/

[2] The total number of deaths in the U.S. was nearing 400,000 at the time of this interview in February 2021.

[3] This exhibition is curated by Kiah Butcher, an artist and filmmaker who is on staff at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, and runs through April 24, 2021. More information about the exhibit is available here.