Dearly Disillusioned

Dearly Disillusioned: Birdseed Collective, Hardly Soft, Odessa, and Pink Progression

McNichols Civic Center Building

144 West Colfax Avenue, Denver, CO 80202

Curators: Moe Gram (“Reminiscing Declarations,” Birdseed Collective), Corianne and Kristopher Wright (“In the Making,” Odessa), Amber Cobb and Mario Zoots (“Trusting Only Ourselves,” Hardly Soft), and Anna Kaye (“Pink Progression”)

January 18-April 5, 2020 (View images of works in the exhibition here.)

Admission: Free

by Mary Voelz Chandler

If you lived in the Denver/Boulder area in 2018 and you appreciate art or create it, you may have visited three exhibitions under the umbrella of “Pink Progression.” Two years ago, area creative dynamos decided to put on a show (shows, actually) with really fine work. This explosion of talent by mainly women, but also by men, served as a response to the outcome of the 2016 presidential election.

The reverberations continue. The Women’s March on Washington took place in January 2017 as well as in many other cities around the world—including Denver—and has recurred each subsequent January. On January 18, 2020, Denver hosted the Womxn’s March [1] in conjunction with the opening of a massive show titled Dearly Disillusioned at the McNichols Civic Center Building.

Featuring work by four artist/curatorial groups—Birdseed Collective, Hardly Soft, Odessa, and Pink Progression—the aim of the exhibit is to commemorate the centennial of women’s suffrage in the U.S. (although notably this is not the centennial for all women) and to expand on the Womxn’s March mission to end inequality and discrimination based on gender identity. [2] Throughout the exhibition, the four segments draw upon societal and environmental concerns, championing shared power, celebrating the vote for women across the country, and the rule of law applicable to all people in equal measure.

This wide-ranging selection of work is laid out in four different areas on McNichols’ third floor, demarcating each group’s contributions and ideas. It is an important exhibition, with many new voices and local art-world favorites.

In the 2018 trio of shows from “Pink Progression” the color pink was part of almost every piece of work. In the 2020 Dearly Disillusioned exhibition, pink is less apparent, with the artists more focused on political matters, the fight against inequality and gender rules, and the importance of women’s roles and history through the ages. [3]

Liz Quan and Sabin Aell, Akin, 2019, porcelain, recycled asphalt shingles, and rubber. Image by Wes Magyar.

In Akin, Liz Quan and Sabin Aell have created a splash of forms made from oddly sympathetic materials: porcelain, recycled asphalt shingles, and rubber. The elements fan out in a dynamic way, with Quan’s sleek ceramic work and Aell’s signature exuberant brushstrokes melding in the expansive installation. Conceptually, what seems to be at work in this piece is a critique of binary categories and hierarchies in terms of art (fine vs. craft), materials (high vs. low), and gender (male vs. female).

Jane Dodge and Judy Anderson, Equality, 2019, fabric, tea bags, thread, and embroidery hoops. Image by Wes Magyar.

Twin sisters Jane Dodge and Judy Anderson worked together on a piece titled Equality, using a mix of fabric, thread, and embroidery hoops. The fiber work in their collaboration shines a light on reality: while we celebrate the centennial this year of the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, not all women were allowed to vote right away. As the artists note, “it took years for all women, regardless of color, ethnicity or class to receive this right.” [4] Small fiber works circle the centerpiece, putting faces to the names of various individual women who fought for all women’s right to vote.

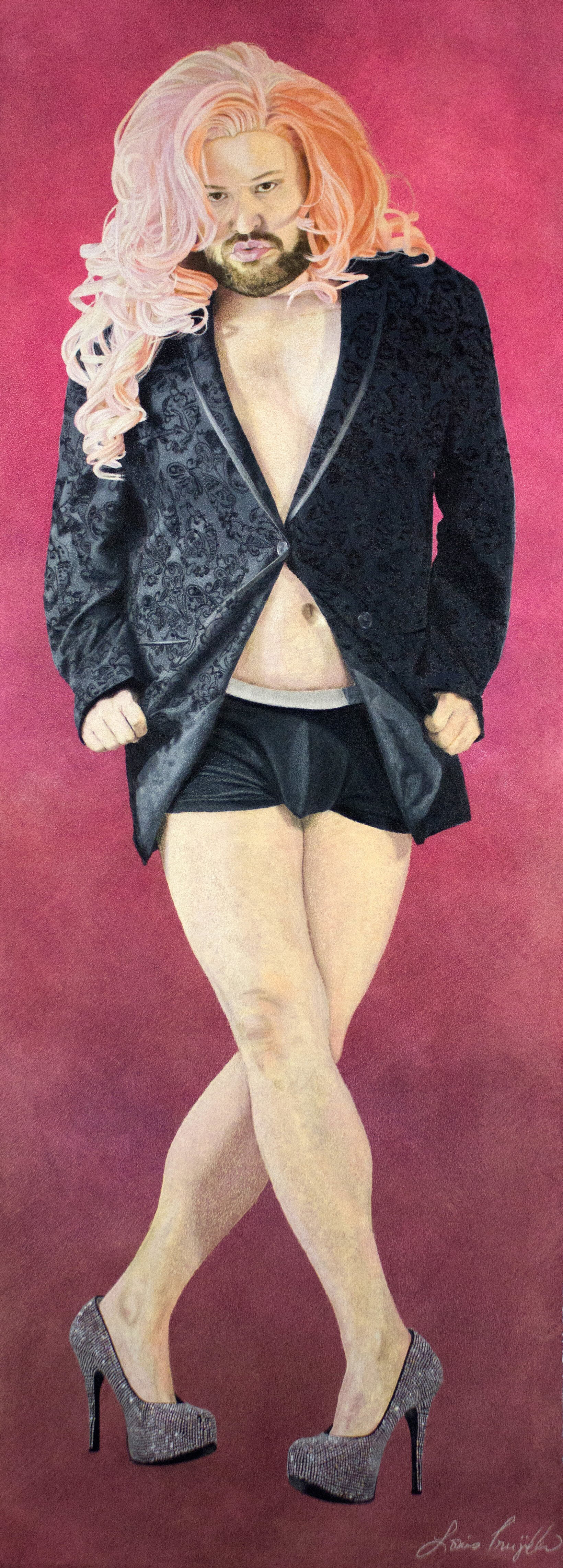

Louis Trujillo Fat, Femme, and Fierce, 2019, colored pencil on paper. Image by Wes Magyar.

Louis Trujillo’s Fat, Femme, and Fierce is a stand-out, with a man wearing short shorts and eye-popping stilettos while sporting pinkish-blonde hair and a beard. Trujillo’s talent using colored pencils tells a story and is right in your face, helping us to understand gender norms as malleable signifiers and inclusivity as a fight against homophobia, fatphobia, and denigrating men who wear colors and apparel associated with women.

The next section of Dearly Disillusioned contains works put together by Odessa: the curatorial team of Corianne and Kristopher Wright. With the title “In the Making” and a statement that succinctly explains that the “exhibition … challenges assumptions of HOW and WHY women make,” Odessa’s goal is to promote dialogue around our expectations of art by women.

Diversity is in the forefront, from a large installation by Talya Feldman involving voices speaking about surviving a mass shooting, to a sensuous glass object by Lindsay Smith Gustave, to a sensitive trio of graphite-on-paper portraits by Laura Dreyer, to a painting by Sierra Montoya Barela that focuses on angles and shadows.

Talya Feldman, After Halle, 2019, 10-channel sound installation mounted on 10 satin acrylic boards. Images by DARIA.

Feldman’s After Halle relies on a 10-channel sound installation mounted on 10 corresponding acrylic boards featuring a triage illustration for first responders. Voices and melodies sing and hum, and we learn these are people who were survivors in a shooting at a synagogue in Halle, Germany in October 2019. Among those 10 voices: the artist herself. The shooter targeted a local synagogue and a shop, killing two people. It was on Yom Kippur.

Gustave works in several mediums, but the piece on view is related to the term used for a passive vessel. Titled Bell Jar, a reference to the glass domes that cover and preserve precious objects, this sensuous piece appears to be sheltering a living thing that is shooting out a stem encased in bright green beads.

Laura Dreyer, Desiree, 2014, graphite on paper.. Image by Wes Magyar.

Sierra Montoya Barela, Untitled, 2019, acrylic on canvas. Image by Wes Magyar.

Dreyer’s Desiree, and her other two portraits, depict young women but with suggestions of vegetal fronds and leaves entwined. Dreyer’s works on view are sensitive and stand out for their quiet power.

And Barela’s untitled painting depicts a corner that could be set in a studio or living room. With long shadows and tilted objects, there is a sense that Giorgio de Chirico is haunting the scene, although it is more spare than his oeuvre.

Conceptual work by Birdseed Collective is curated by Moe Gram, with involvement by Meredith Feniak, Karma Leigh, and Kaitlyn Tucik. A projection and installation are titled Reminiscing Declarations, and the words projected certainly live up to that description:

The history of mankind

is a history of

repeated injuries and usurpations

having an absolute tyranny over her

in the formation of which

she has no voice

We are here again to say

A detail of Reminiscing Declarations by Meredith Feniak, Karma Leigh, and Kaitlyn Tucek, 2020, projector and mixed media installation. Image by DARIA.

The angled lines are projected into a corner of the gallery, with letters outlined in pink. Poetic, defiant, and exactly right—this piece is fitting in the overall breadth of Dearly Disillusioned. The installation next to the projection holds three mirrors hung over shelves on which a microphone can rest. Also on each shelf is a stack of small pieces of paper with different topics. As the signage for this part of the show notes, “Guests are encouraged to take a memorandum as they experience the work.”

Finally, Hardly Soft presents “Trusting Only Ourselves,” curated by members Amber Cobb and Mario Zoots. Two artists are part of the exhibition: Masha Sha and Tomás Diáz Cedeño.

The curators’ statement is spot on: “The exhibition curators deliberated the effects of living in chaos for more than 1,000 days, noting the way the sense of urgency has adapted with time’s intervention and how the friction and force create an invisible weight.”

Yes.

Tomás Diáz Cedeño, Sendero de Piedra, 2020, rope and plastic ties. Image by DARIA.

Tomás Diáz Cedeño alludes to the current political climate through three large sculptural images hanging on a long wall. All are titled Sendero de Piedra (Stepping Stones), and all are created using segments of fuzzy-looking rope and plastic ties that appear to be quite prickly. Each work intricately depicts the patterns of plants, but significantly references specimens along the Mexico-U.S. border and by extension the atrocities so many have faced there.

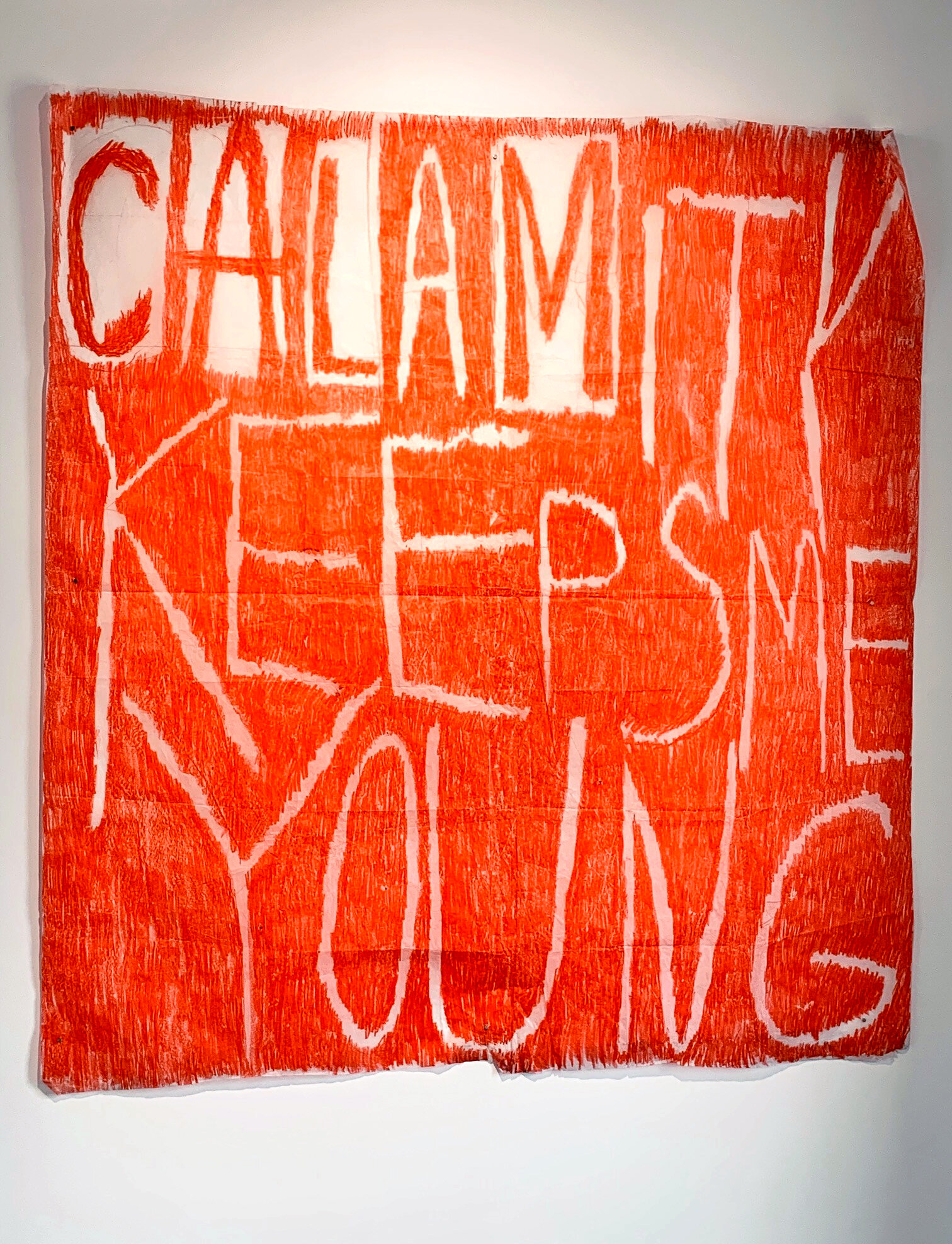

Masha Sha, Calamity Keeps Me Young, 2019, lumber crayon on tracing paper. Image by Mary Voelz Chandler.

And if “living in chaos for more than 1,000 days” can be stowed away at some point, Masha Sha revels in irony, in despair, and in the weight many people feel. Her three large tracing paper drawings include two that are in dark and murky colors yet the third literally screams out to be read. Calamity Keeps Me Young in giant letters is the final image in Dearly Disillusioned.

I can’t imagine a more fitting conclusion. Dearly Disillusioned teems with uplifting themes such as gender equality and diversity and inclusion and suffrage and aspiration. But then, there is the reality that smacks you in the face: Calamity Rules.

Mary Voelz Chandler writes about visual arts, architecture, and preservation. She held the position of art and architecture writer for many years at the former Rocky Mountain News in Denver. She has completed two editions of the Guide to Denver Architecture and was a co-author of the 2009 book Colorado Abstract with Westword critic, author, and historian Michael Paglia. Along with numerous awards for her writing, Chandler was honored by the Denver Art Museum in 2012 with the Contemporary Alliance “Key” Award, and received the AIA Colorado 2005 award for Contribution to the Built Environment by a Non-Architect.

[1] The organizers of the Womxn’s March Denver define “womxn” as “those targeted by sexism.” Womxn is also widely recognized as a term used to include transgender women. https://www.womxnsmarchdenver.org/our-mission.html.

[2] Their stated mission is as follows: “Womxn's March Denver is a collective of womxn* committed to amplifying marginalized voices in the movement to end sexism, oppression, and injustice. Through community engagement, protest, education, and leadership, we leverage our platform to ignite action.” https://www.womxnsmarchdenver.org/our-mission.html.

[3] After the exhibition at the McNichols Building, “Pink Progression” moves to three other venues. From June 4 through August 23, “Pink Progression: Collaborations” settles in at the Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities, followed by an exhibition featuring a selection of work from the two earlier Pink Progressions at the O’Sullivan Gallery at Regis University. Finally, “Pink Progression: In Skin” wraps up a year of focus on equality from October 13 through November 13 at Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design. For more details, visit: http://www.pinkprogression.wordpress.com.

[4] As the artists note in the centerpiece of the work, Native American women were granted the right to vote in 1924, Asian American women in 1952, African American women in 1964, and Latin American women in 1975.