The Distance Between Words

Joel Swanson: The Distance Between Words

New Collection | The Vault

3758 Osage Street, Denver, CO 80211

October 1, 2022-April 15, 2023

Admission: Free

Review by José Antonio Arellano

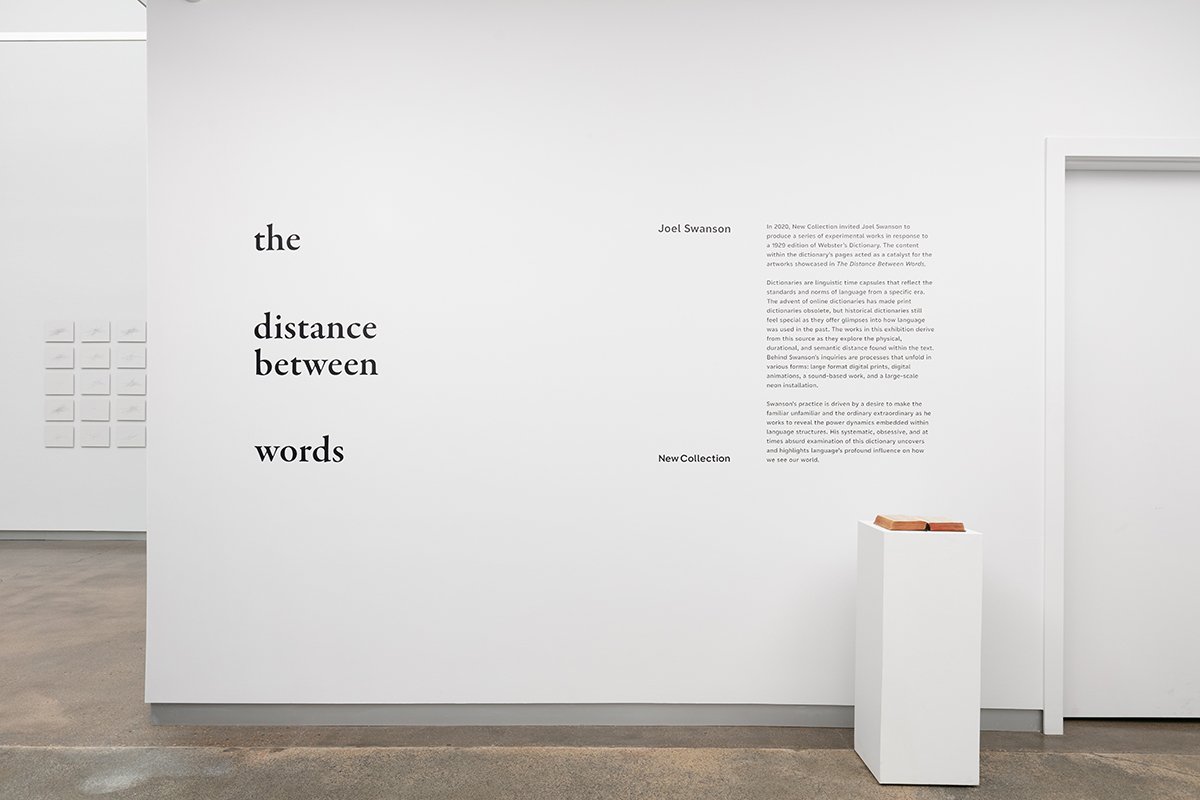

For well over a decade, Joel Swanson has explored how language and technology structure our lives. His work has appeared in the Denver-land area, not to mention the Venice Biennale. As part of the entrepreneur Nicholas Pardon’s New Collection, a project-based arts initiative, artists Amber Cobb and Mario Zoots prompted Swanson to create the pieces that make up the current exhibition. The Distance Between Words is on view at Pardon’s private gallery The Vault.

A view of the title wall of Joel Swanson’s exhibition The Distance Between Words at The Vault at New Collection in Denver. Image by Wes Magyar.

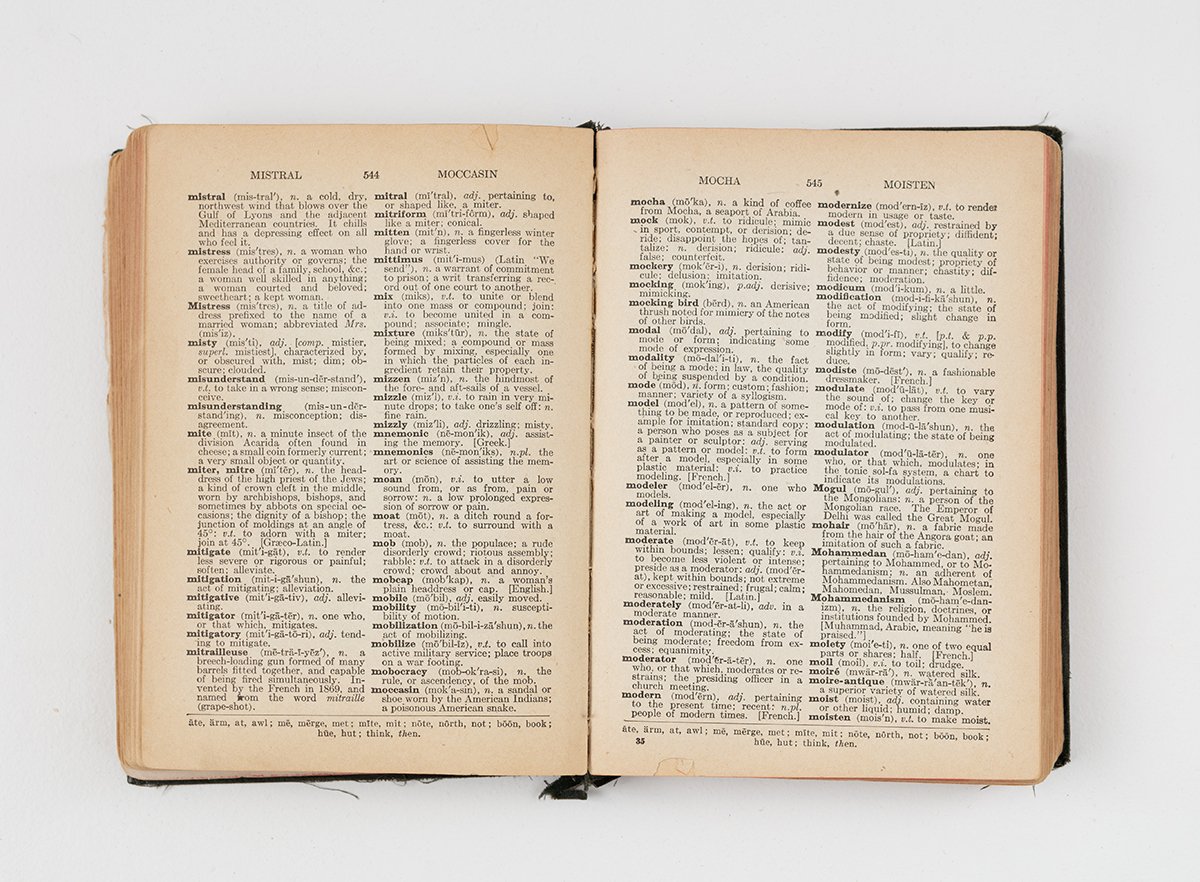

Cobb and Zoots handed Swanson a 1929 edition of Webster's College, Home and Office Dictionary and invited him to play. As dictionaries go, this edition boasts its Websterian pedigree with the inclusion of various glossaries and tables. [1] The dictionary’s selection criteria elude me.

There are graphs listing census data and information including the “Occupations of Persons 10 Years Old and Over in the United States.” There is a map of American mail routes in operation; color plates of collections including “Eggs of Various American Birds”; a glossary of aviation terms; the latest radio antenna information; and so forth. The fact of the information’s inclusion imbues the apparently random material with an aura of meaningful authority. This is how information is collated and circulated, thereby becoming “common knowledge” to those who have access.

The 1929 edition of Webster's College, Home and Office Dictionary on display in The Distance Between Words exhibition. Image by Wes Magyar.

Because Swanson dismantles the dictionary as an object and archive of knowledge, we could characterize his work as deconstructive in the theoretical sense of the term. He exposes some of the conventions that organize and render content.

From Swansons’ statement: “This series of prints and animations explore the nuances of the codex book and antiquated supplementary additions found within Webster’s Dictionary from 1929. The unique and curious additions include census data, radio antenna diagrams, and other oddities reflecting the times in which the dictionary was published.”

An installation view of Joel Swanson’s exhibition The Distance Between Words at The Vault. Image by Wes Magyar.

The Vault’s minimalist tenor helps to activate the work and our appreciative relation to it. Swanson renews a creative trajectory described by Sol Lewitt and Victor Burgin in the late 1960s. [2] This trajectory emphasizes the motivating ideas and concepts instead of the created objects.

The “sufficient conditions” establishing this kind of work as art, writes Burgin in an infamous footnote, thus necessarily include the psychological state of the viewer. The “art object becomes, or fails to become, a work of art in direct response to the inclination of the perceiver to assume an appreciative role.” [3] This is art to the extent that we are willing to acknowledge it as such.

Works from Joel Swanson’s Every Page series on display in The Distance Between Words exhibition. Image by Wes Magyar.

While driven by ideas, Swanson’s pieces are nevertheless meticulous, poetic in ambition, and graceful in execution. Like poets, Swanson forces us to slow down and pay attention to the gaps between words we tend not to register. A facility with linguistic use can render language almost transparent, as if we see through it to capture the world it delivers. But when language breaks down, as it does in The Distance Between Words, we can catalogue the opacity of its mechanics.

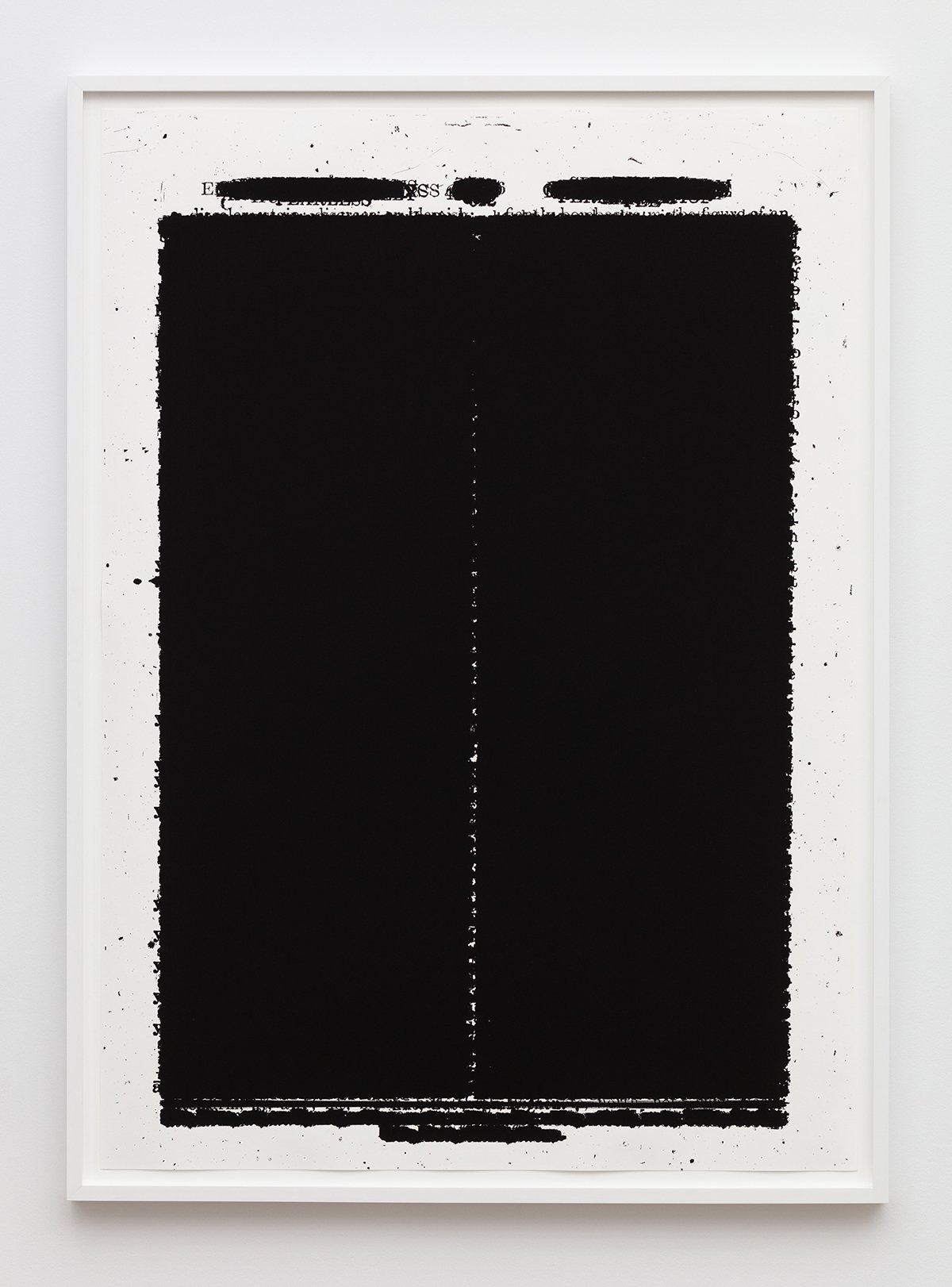

Joel Swanson, Every Page (Verso) and Every Page (Recto), 2022, digital prints on paper, 56 x 40 inches each. Image by Wes Magyar.

Swanson literalizes this insight in Every Page (Recto) and Every Page (Verso), in which he scans the right-hand (verso) and left-hand (recto) side of every page of the 1929 dictionary. He layers the scanned pages and prints them on large sheets of paper to produce two large prints. The resulting pieces look like monochromatic paintings, the rectangular material supports of which are determined by the shape of the dictionary page. The handset leading and font of the original dictionary are barely recognizable as the layered text becomes illegible in the accumulated mass of ink. Ink, in the prints, becomes noticeably more inky.

Joel Swanson, Every Page (Verso), 2022, digital print on paper, 56 x 40 inches each. Image by Wes Magyar.

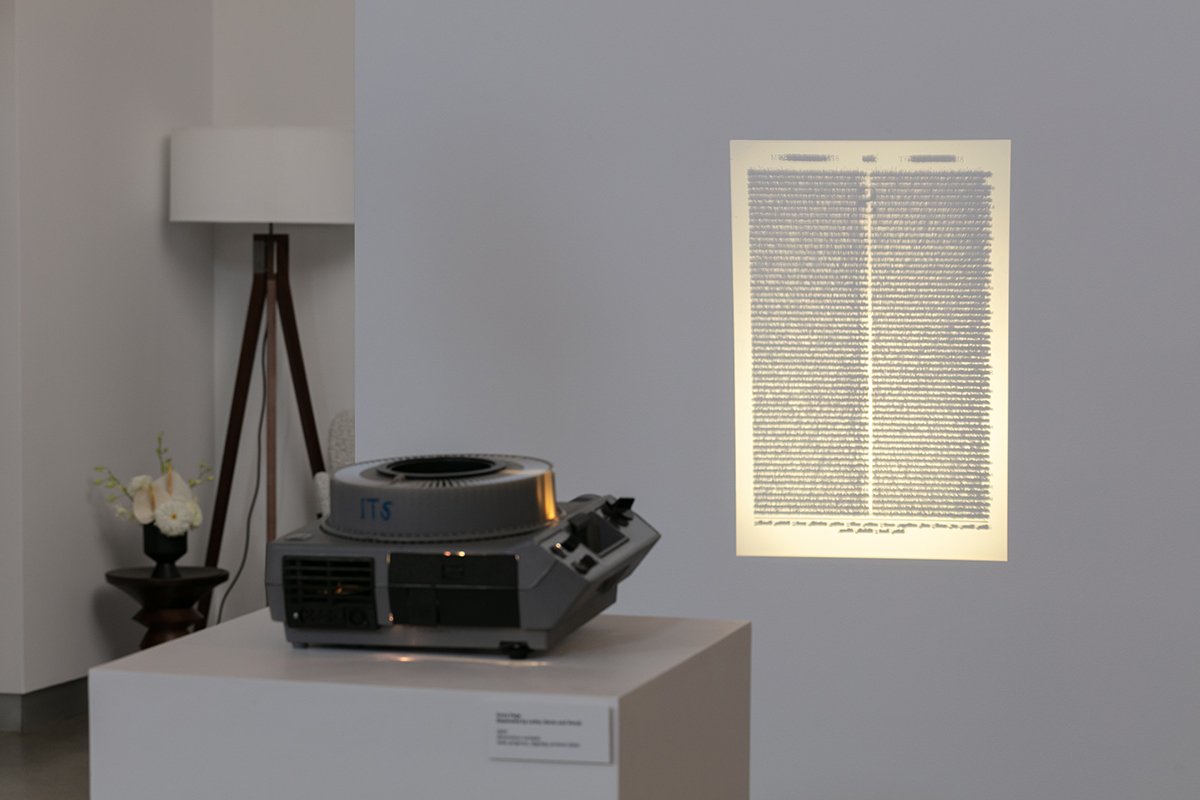

Unlike these printed accumulations of ink, a neighboring piece Every Page (Separated by Letter, Recto and Verso) allows us to look through the material support of the printed word: the page. Swanson scanned all of the pages of a dictionary, transferred them to a transparent medium, then stacked these scans and made a single image of them separated alphabetically. By projecting the images onto the wall using a carousel slide projector, he lets us see the stacked printed words. The idea of paper, here, is rendered transparent, while the ink does not densely amass on top of itself so much as it ephemerally floats.

Joel Swanson, Every Page (Separated by Letter, Recto and Verso), 2022, slide projector and digitally-printed slides, dimensions variable. Image by Wes Magyar.

The day I saw this piece, the projector was stuck on a slide, failing to advance to the next image. When our tools break down mid-use, as Martin Heidegger noted in 1927, we tend to notice their materiality. [4] And that, I think, is the point of this work, even if—especially if— its enabling technology stops working.

Swanson’s use of a projector thus appears as an atavistic nod to older technology and as an homage to the developments in conceptual art of the 1960s and 1970s. [5] Swanson revisits the earlier twentieth-century philosophical concerns that paved the way for this kind of art—the self-conscious impulse that characterizes what we have come to call modernism.

The slide image for the letter V in Joel Swanson’s Every Page (Separated by Letter, Recto and Verso). Image by Wes Magyar.

Think of Viktor Shklovsky, who in 1917 described art as rendering the familiar unfamiliar. “Art,” for Shklovsky, “exists that one may recover the sensation of life… to make the stone stony.” [6] Think, too, of how Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, also in 1917, asked the art beholder to consider the very conditions that enable art to register as art.

The loss of faith in rationality we tend to associate with the end of the 19th century led to efforts exploring the very nature of mediation—in art and language, math and logic. Artists explored the mediating conditions enabling their work, and philosophers of various traditions explored the very possibility of knowledge and meaning. Some mathematicians and analytic philosophers expressed a desire to pin down language to math, and to equate math with logic. If only we can do that, they thought, we could disclose, once and for all, the logical foundation of language—and through it everything else.

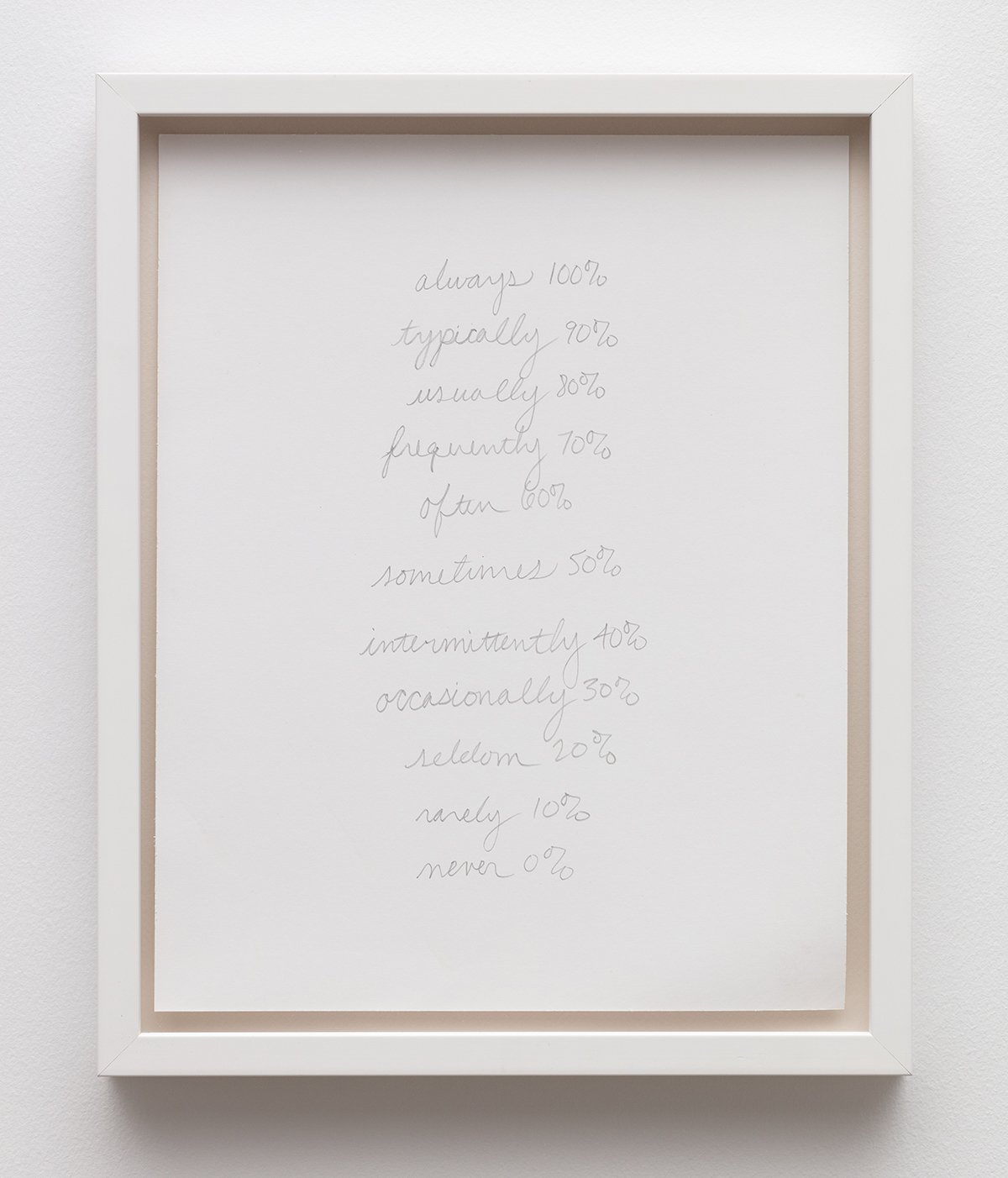

Joel Swanson, Frequency Adverbs, 2022, graphite on paper, 14 x 11 inches. Image by Wes Magyar.

Swanson plays with something like this desire in two pieces titled Frequency Adverbs. Swanson, as the gallery guide states, translates “natural language… which is messy and subjective” into “mathematical language, which is precise and discrete.” In the first piece, he presents a list of words including “usually” and “frequently,” “intermittently” and “occasionally,” and assigns percentages that gesture toward the words’ meanings.

Joel Swanson, Frequency Adverbs, 2022, neon and electronics, 156 x 336 x 4 inches. Image by Wes Magyar.

On the gallery wall directly across from this list, an accompanying installation renders the words in neon signs lit according to the assigned percentages. The neon sign “ALWAYS” remains lit 100% of the time; “FREQUENTLY” only 70%; “SELDOM” 20%; “NEVER” remains unlit. The illumination of electronic neon glow thus sheds light, as it were, on what we colloquially refer to as “shades of meaning.”

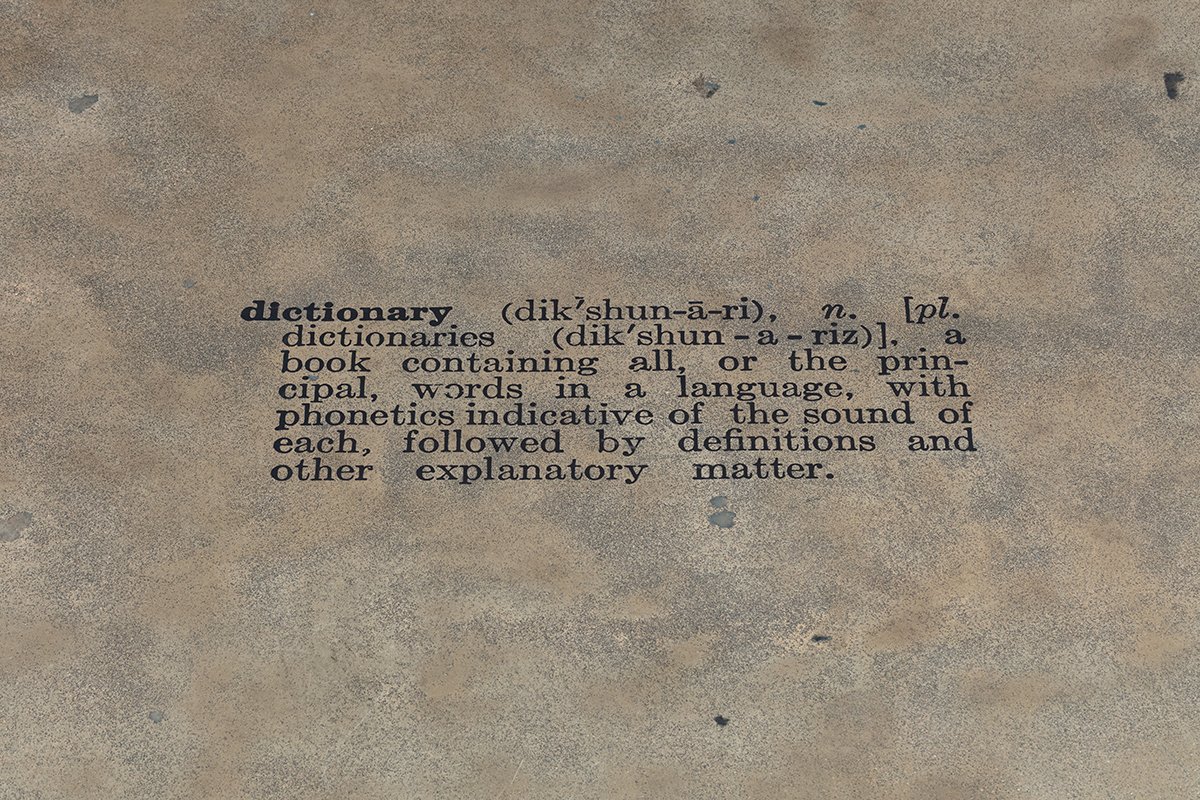

Joel Swanson, The Definition of Dictionary, 2022, found dictionary definition and vinyl, 60 x 23 inches. Image by Wes Magyar.

As I considered whether the work expresses faith in the desire to assuage the messiness of language with the objectivity of math, I happened to be standing near the definition of “Dictionary” printed on the gallery floor. The inclusion of this definition, taken from the 1929 dictionary, acknowledges the conceptual art of Joseph Kosuth and alludes to the conditions of the show’s production.

This self-referential use of an item from a dictionary (a definition) as a work of art within a set of works (the exhibition) reminded me of the paradoxes involving sets that contain themselves as items. In the late 1920s, Kurt Gödel used mathematical reasoning to explore itself and such paradoxes and he exploded the possibility of math being provably, logically consistent. With Gödel’s insight in mind, we might say that whatever our understanding of semantic nuance is, it cannot be pinned down to mathematical formal calculation. [7]

Joel Swanson’s The Meaning of Lines series, 2022, digital animation and digital prints on aluminum. Image by Wes Magyar.

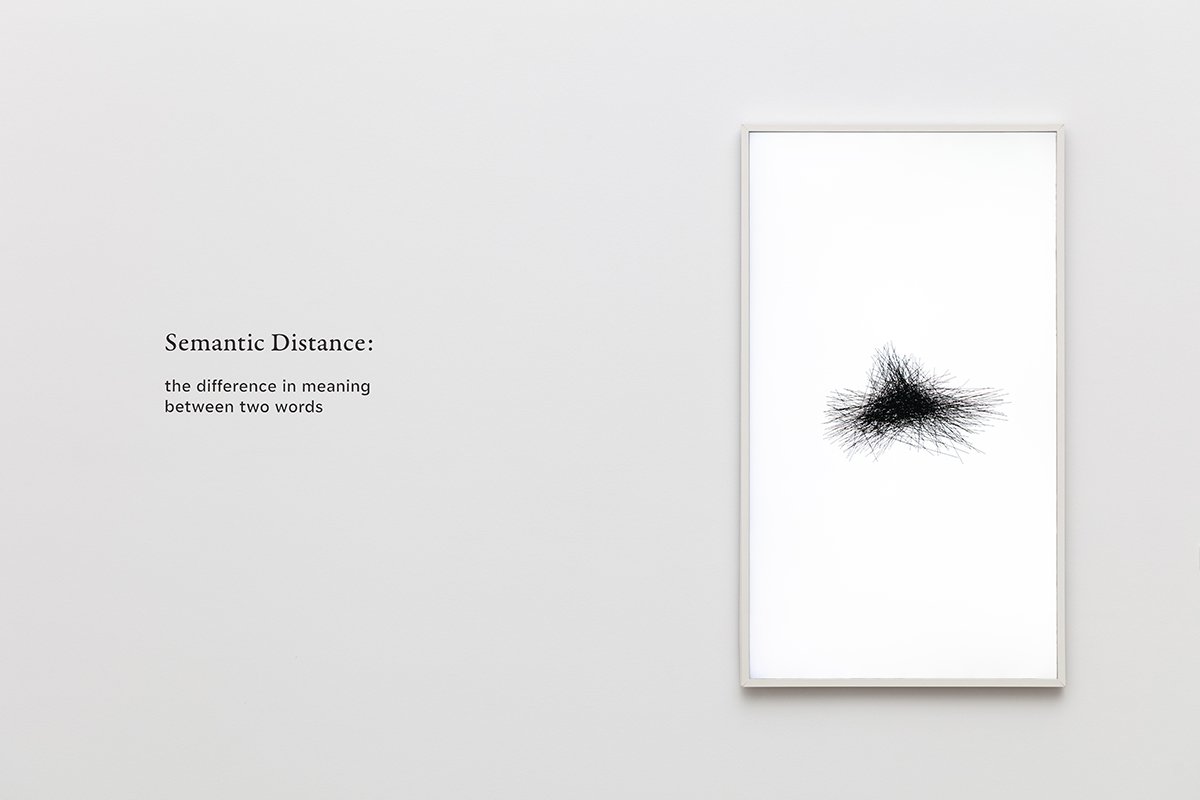

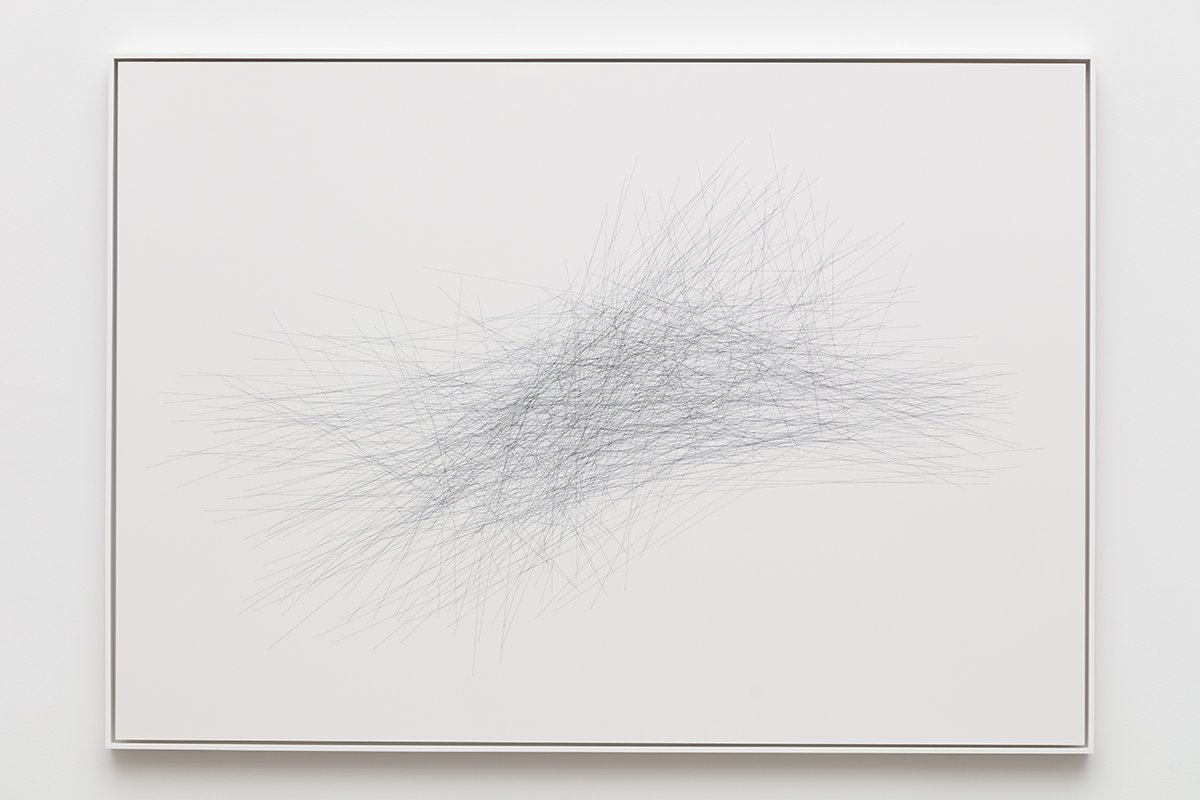

And neither can meaning. In his Meaning of Lines series, Swanson updates an interest in language’s organizing power by introducing algorithmic applications that increasingly structure our everyday. He uses the 1929 dictionary’s content as the input data for a program that calculates the frequency with which words appear next to each other (how Google and iPhones can seemingly predict what you will type next).

Joel Swanson, The Meaning of Lines (All Headword Pairs Animated), 2022, digital animation, 46 minutes 16 seconds. Image by Wes Magyar.

The program maps out the semantic “distance” between the guide words atop the dictionary page (say, “education” and “effusion”) and expresses this distance as lines in three-dimensional space. The resulting video is elegantly meditative, as are the accompanying aluminum prints of this series.

Joel Swanson, The Meaning of Lines (All Headword Pairs), 2022, digital print on aluminum, 48 x 67 inches. Image by Wes Magyar.

If we think of meaning as the correspondence between one set of symbols and another, or one set of symbols and the world, then these lines are verifiably meaningful. The meaning of this piece as art, however, surpasses verification and formal manipulation. It might expose the technological utopians’ fantasy about the corrective power of algorithmic logic.

Joel Swanson, The Meaning of Lines (A Headword Pairs)–(Z Headword Pairs), 2022, digital prints on aluminum, 11 x 8 inches each. Image by Wes Magyar.

In this fantasy, the right formula, application, calculation, or algorithm would clear up the messiness of subjective perception, biases, and semantic confusion. But what occurs when we abdicate our responsibility and offload it to technological fantasies involving the supposed objectivity of algorithmic logic?

This question and its potential answer were made available to me almost as a revelation in the audio piece All the Silence. Swanson had a program mechanically “recite” the dictionary’s content but then eliminated the sound of the recited words. He left only the durational spaces between the words, thereby rendering the sound of silence in between spoken words. Without such punctuated silences, however minuscule, spoken language could become an incomprehensible jumble of noise.

Joel Swanson, All the Silence, 2022, digitally processed audio, 20 hours 2 minutes 42 seconds. Image by Mario Zoots.

The piece is played through a wireless speaker at a low volume. You can just barely hear the endings and beginnings of the mechanically-uttered words. This is not the melodious murmur or soothing sibilance of spoken sound. This cold, mechanistic recitation, audible for only fractions of a second, is discomfiting. I begin to envision a world in which we abnegate our responsibility, outsource it to the technology that will supposedly save us from ourselves, and in the process erase the very possibility of our self-recognition of us as us.

All the Silence appears so simple, but it allows us to recognize what has been a topic of western philosophy since Plato—an interstitial space, an in-between substratum, the void through which meaning as such shines forth. [8] What I am trying to say is that this work compels us to recognize an ineffable something through which everything about us as us depends: what is excluded as the condition of something being the thing it is, and what is included as the expression of its structuring forces. Our recognition of ourselves as that which considers the conditions of our own being.

A view of Joel Swanson’s Frequency Adverbs and The Meaning of Lines series at The Vault at New Collection. Image by Wes Magyar.

This is technology understood not as instrumentally ready to extract the world’s resources but as poesis. [9] This use of technology can produce the clearing through which we create and bring forth, recognize and understand, experience and elevate. [10]

The conditions prompting this exhibition create a cordoned-off zone that can seemingly bracket market pressures. The point here is creation, not commodification. The type of value at play here is thus that of a collector and not the market. And maybe, just maybe, this space can enable the creation of meaning that is not subjected to the sociology of market desires. In my view, this is the ideal condition for the creation of art as such.

The 1929 edition of Webster's College, Home and Office Dictionary that was the basis for Joel Swanson’s exhibition The Distance Between Words. Image by Wes Magyar.

But what, we have to ask, makes this zone possible? The market, while being displaced, hovers in the background. The specific year of the Webster dictionary appears not to have played a role in its selection. But I cannot help but consider the exhibition in relation to the 1920s, a decade that witnessed the creation of some of the most compelling, self-aware works of modernist art.

1929 was the year Rene Magritte’s The Treachery of Images (1929) asked its beholders to consider the difference between the presentation of objects in the world and their iconic and linguistic representation. But it is also the year of the stock market crash that inaugurated the most devastating economic catastrophe in American history, the beginning of the Great Depression, and the end of the economic boom that resulted in gross inequality.

A view of Joel Swanson’s The Distance Between Words at The Vault at New Collection. Image by Wes Magyar.

This art will not move your passions, nor incite your political fervor. Although it could. For if the aesthetic realm is understood as existing within a cordoned-off zone, that which is excluded (the market, politics, social anxieties…) applies such pressure to the boundaries that these borders could collapse with a single thought that lets them in. And insofar as this kind of work requires that we assume an appreciative role, there is a sneaking suspicion that we may not want to. I think we should because what we might discover is the insight that only art can disclose.

José Antonio Arellano (he/his) is an Assistant Professor of English and Fine Arts at the United States Air Force Academy. He holds a Ph.D. in English Language and Literature from the University of Chicago. He is currently working on two manuscripts titled Race Class: Reading Mexican American Literature in the Era of Neoliberalism, 1981-1984 and Life in Search of Form: 20th Century Mexican American Literature and the Problem of Art.

[1] “In his earliest Dictionary,” writes John C. Rolfe, “Webster had introduced an Appendix, and this together with the admission of a great number of scientific and technical terms… gave his American Dictionary something of an encyclopedic character…” “The Origin and History of Dictionaries,” Webster's College, Home and Office Dictionary Illustrated, Noah Webster and Harry Thurston Peck (Chicago: Consolidated Book Publishers. 1929), vi.

[2] See Sol LeWitt “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” Artforum 5 no. 10 (June 1967), 79.

[3] Victor Burgin, “Situational Aesthetics,” Studio International, 178, no. 915 (October 1969), 121 footnote 4.

[4] See Martin Heidegger, §14 “The Being of the Entities Encountered in the Environment,” Being and Time: A Translation of Sein Und Zeit. Translated by Joan Stambaugh (State University of New York Press, 2010).

[5] Robert Barry’s 1960’s experimentation with slide projectors is relevant here, as is Ian Burn’s investigation of iterative copies in Xerox Book (1968). Mel Bochner’s playful exploration of the phrase “LANGUAGE IS NOT TRANSPARENT,” printed on various media including glass, also paved the way for Swanson’s art.

[6] Viktor Shklovsky “Art as Technique” reprinted in Art in Theory, 1900 - 2000 an Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2005), 279.

[7] My point here, one that was brought to my attention by Roger Penrose’s The Emperor's New Mind: Concerning Computers, Mind, and the Laws in Physics (1989), is that our understanding and insight is not algorithmic in nature. When converted to mathematical calculations to show their truth or falsity, linguistic statements such as “This statement is false,” or “This sentence is a lie,” or “This statement cannot be proved” cannot be proven mathematically using the rules of a formula. If such statements were shown to be true, they would be expressing something false. But if they were expressing something false, they would be true. But if they were shown to be true, then what they state would be false. And so on, ad infinitum. We can understand the meaning of such sentences even when we cannot prove them.

[8] See Jacques Derrida’s “Khôra” in On the Name (1993) in which he riffs on Plato’s Timaeus.

[9] See Martin Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology: And Other Essays (New York: Garland, 1977).

[10] See Heiddeger’s §28 “The Task of a Thematic Analysis of Being-In” and §36 “Curiosity” of Being and Time, in which Heidegger refers to a “Lichtung,” translated as a “clearing.”