Plane of Action / Just As I Am / A Home In Between

Kevin Hoth and George P. Perez: Plane of Action

Kristopher Wright: Just As I Am

Erin Hyunhee Kang: A Home In Between

Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art (BMoCA)

1750 13th Street, Boulder, CO 80302

September 29, 2022-February 19, 2023

Curated by BMoCA and Pamela Meadows

Admission: $2, Saturdays are free for all

Review by Maggie Sava

BMoCA kicked off their fall season with three exciting new exhibitions: Kevin Hoth and George P. Perez: Plane of Action, Kristopher Wright: Just As I Am, and Erin Hyunhee Kang: A Home In Between. These shows are all connected by the artists’ impulse to push the potential of photography as form and medium through distinctive methods and processes. The result is a wonderfully multifaceted program in which the simultaneous harmony and particularities within the three exhibitions expand photography practices and create a cathartic interplay between themes of transforming the mundane, destruction, (re)construction, memory, healing, and hope.

An installation view of Kevin Hoth and George P. Perez’s exhibition Plane of Action at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art. Image by Maggie Sava.

The first show you encounter upon entering the museum is Plane of Action, which features the work of Kevin Hoth and George P. Perez. The two artists manipulate and distort photographs as a way of questioning how far you can push the medium before it becomes something new altogether. Hoth’s and Perez’s works are interspersed throughout the space, and the resulting cohesion reveals a satisfying kinship between their artworks.

George P. Perez, Neck Stretch, 2022, reclaimed ceramic tile and ceramic photo image, 32 x 50 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

Some of Hoth’s pieces hang from the ceiling as if floating in the air—a departure from the tradition of displaying framed photographs on the wall—which highlights their physical structure and dimensionality. Perez’s ceramic-based art rests on a table and, in the case of Neck Stretch (2022), on the floor, emphasizing that they are sculptural works.

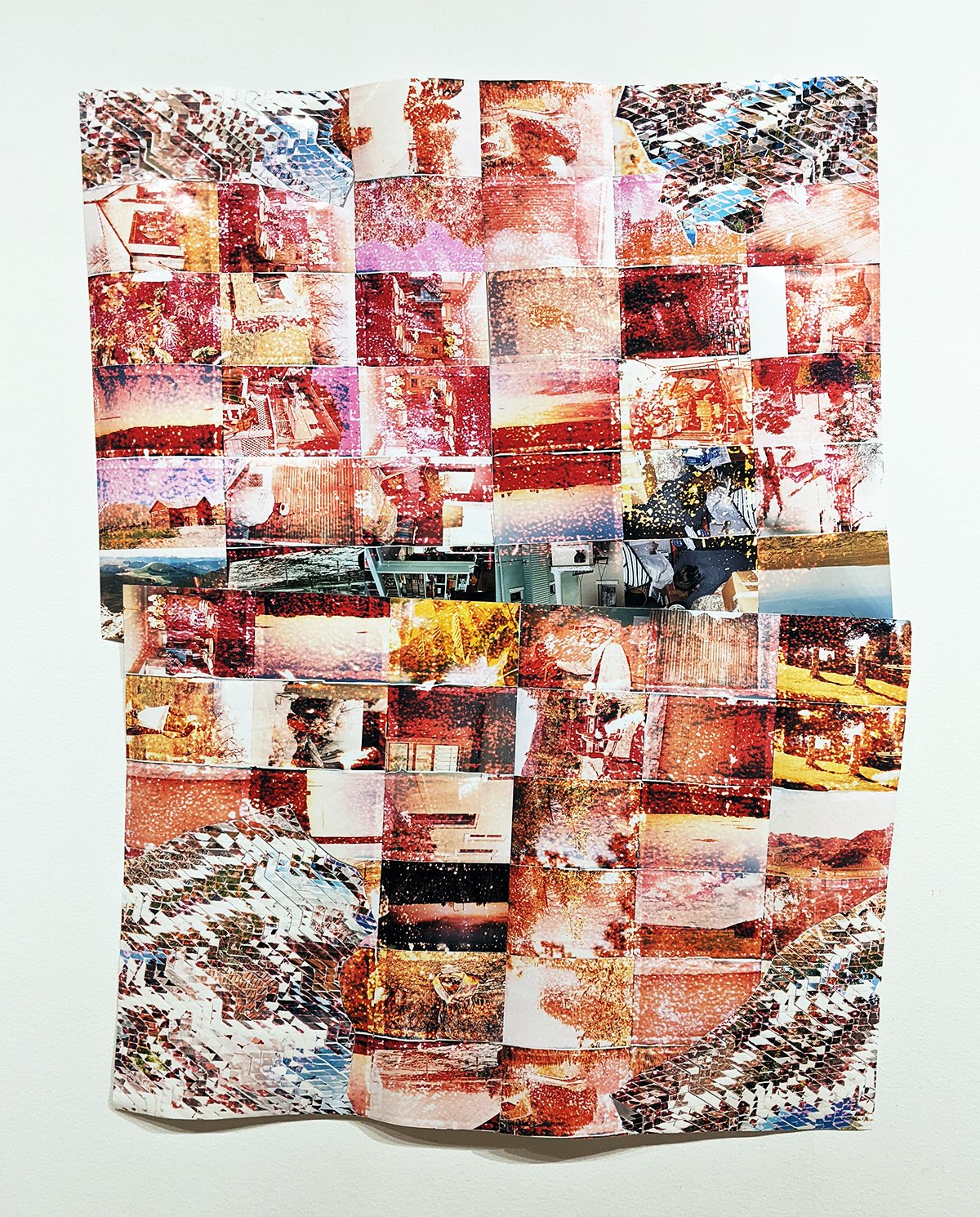

George P. Perez, Overlaps and Merging Images Lines Over, 2022, C-prints and tape, 36.5 x 46.25 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

Hoth and Perez sometimes source found photographs and sometimes take the photos themselves. They then radically transform the core structure of the images in order to make photography sculptural, furthering a practice in contemporary art in which artists prioritize the material nature of the photograph. [1] In Overlaps and Merging Images Lines Over (2022), Perez creates a textile-like form from collaged C-prints quilted and taped together, including rectangular blocks and smaller sections of tessellating prints that he fragments and rearranges to create detailed patterns.

A detail view of George P. Perez’s Overlaps and Merging Images Lines Over, 2022, C-prints and tape, 36.5 x 46.25 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

The imperfections of the C-prints in Overlaps and Merging Images Lines Over show in the white spots, the overexposures, and the orange, yellow, and pink hues of the images. [2] While obscured, the subject matter is not lost—looking closely, you can still see a portrait of an older gentleman sporting glasses and a baseball cap, the back of someone’s head, and someone loading the trunk of a car. Perez’s inclusion of these mundane photos with the natural distortions of the prints resembles the aesthetics of memory and how it can alter, shift, and, over time, fade while still contributing to a collective cloth of identity and community.

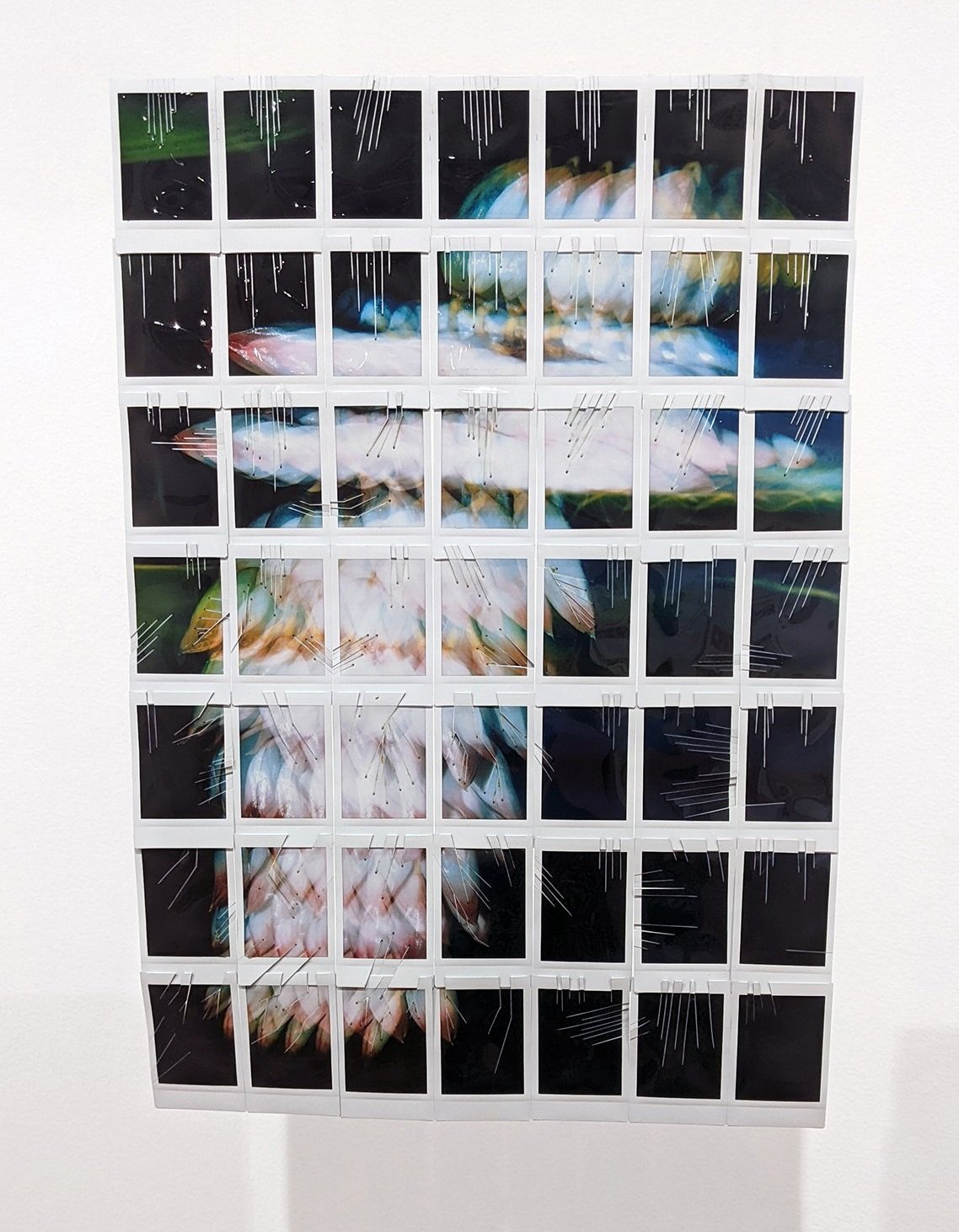

Kevin Hoth, Alpinia 01, 2019, instant film collage. Image by Maggie Sava.

Alongside Perez’s (re)construction is Hoth’s distinctive form of photographic deconstruction. Plane of Action features works from his Immortal Chromatic series, where Hoth uses images of flowers to reckon with the traumatic brain injury of a loved one. He starts by taking digital photographs of flowers, then cuts them up into a grid that he makes into instant film modules. He cuts and burns these modules as they develop, creating “wound” like effects which transform “into the sculptural scar.” [3] The randomness in the marking of Hoth’s images evokes the notion of different possible outcomes and results that happen after we make certain choices or events occur, particularly traumatic events which have the power to drastically change the direction of our lives. [4] For Hoth, this artistic process helps capture his healing process, with the reconfigured flowers providing a sense of hope among the visible scars on the prints.

Kevin Hoth, The Light and the Dark, 2020-2022, instant film collage. Image by Maggie Sava.

Hoth pushes the obfuscation of the image the furthest in The Light and The Dark (2020-2022). Composed of two photo-grids framing one of the gallery doorways like wings, The Light and the Dark is a collage of instant film prints that appear blank. Instead of capturing an image through the lens of the camera, Hoth cuts and burns designs, creating compositions through the physical destruction of the prints. In turn, this artwork questions whether there is any photography involved at all. Is light still used to expose the prints? Do the physical alterations serve as a violent form of post-production?

Like Perez’s work, Hoth’s interventions are not irreverent or negative in nature. Rather, in challenging photography as a medium through a combination of digital and analog interventions, Perez and Hoth contribute a renewed energy, interest, and dedication to it. Together, their works create something altogether new which still manages to contain the vital essence of emotion, memory, and connection imbued in photographs.

An installation view of Kristopher Wright’s exhibition Just As I Am at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art. Image by Maggie Sava.

In the next gallery we find Kristopher’s Wright’s solo debut Just As I Am. Hung throughout the room, which wraps around the museum’s central staircase, are sixteen new works in which collaged found images meet vibrant fields of color. Combining screen printing, painting, and drawing, Wright captures the absorbing and encompassing memories of the simple, yet profound, life events of the strangers within the found photographs he translates onto the multimedia canvases. Wright makes these moments familiar through a fusion of the archival language of the photographs with dreamy, cartoon-like details of the brightly painted components.

On the left: Kristopher Wright, Fire In My Bones, 2022, acrylic ink and paint on canvas, 6 feet x 7 feet x 2.5 inches. On the Right: Kristopher Wright, Come By Here, 2022, acrylic ink and paint on canvas, 4 feet x 4 feet x 1.5 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

In Fire In My Bones (2022), a mother and a daughter sit at a table together, in a snapshot of celebration. The child leans over the table, blowing candles out on an orange and white polka dot birthday cake. The kitchen is full of blue hues contrasted by the yellow wall. A vase of flowers rests on the table, and a pineapple sitting next to a bowl of fruits accents the kitchen window. White outlines of a machine diagram overlay the figures and part of the table, as if mirroring their anatomical components and making them appear as parts of a larger machine. These diagrams depict these moments as “social engines” and allude to the constant work of personal repair throughout one’s lifetime. [5]

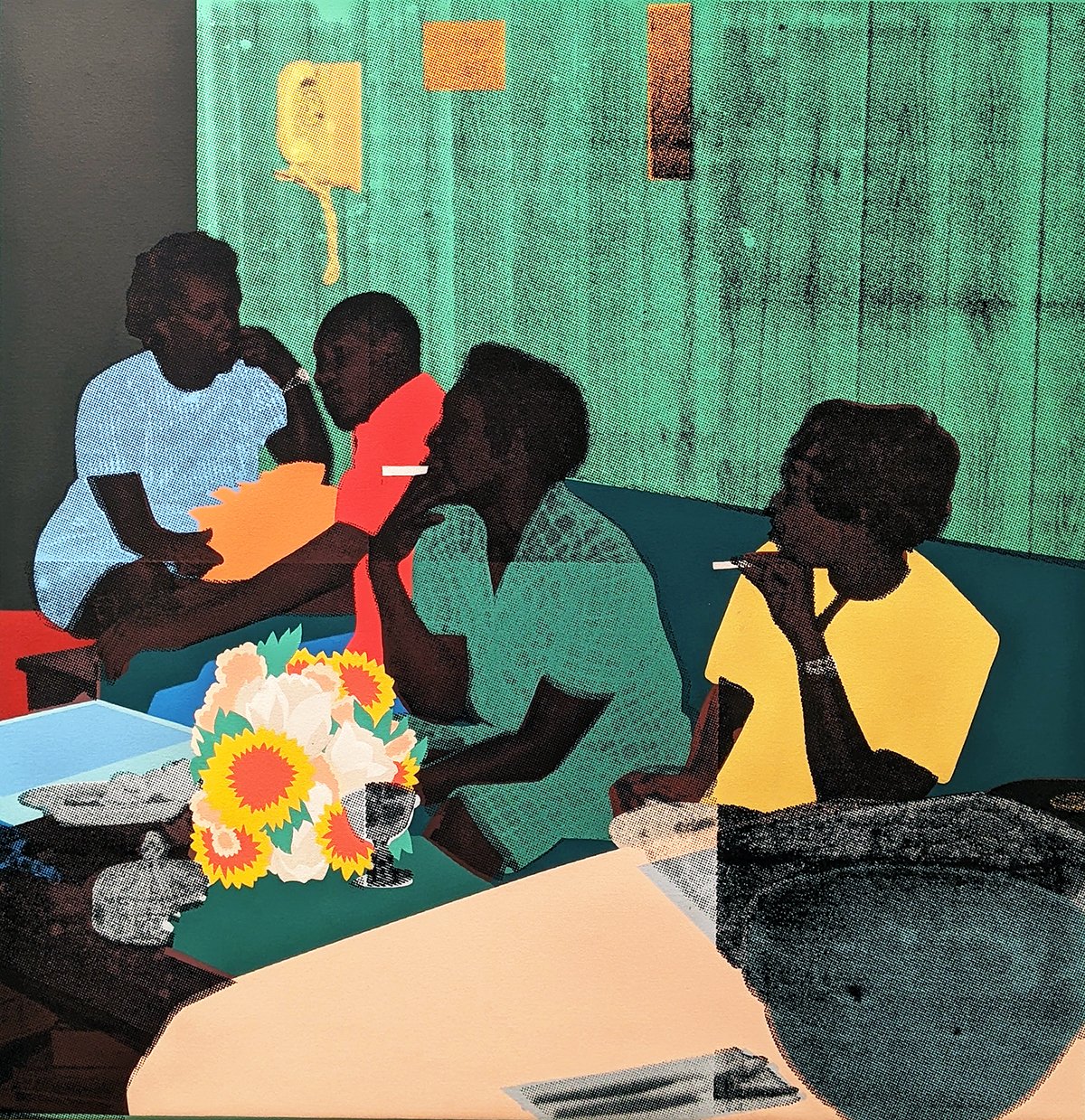

Kristopher Wright, Come By Here, 2022, acrylic ink and paint on canvas, 4 feet x 4 feet x 1.5 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

Hung right next to the birthday scene, as if an extension of the story playing out beside it, is Come By Here (2022). In it, three women and a man dressed in bright blue, orange, green, and yellow, sit around a table chatting and smoking, as if they are family members sitting in the next room over as the birthday festivities go on beside them. The comfort of the scene and the almost otherworldliness of the living room transform it from a particular space into a more universal space, as if the living room might be in anyone’s home.

Kristopher Wright, Summer Cypress, 2022, acrylic ink and paint on canvas, 6 feet x 9 feet x 1.5 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

Stylistically, Wright’s work is evocative of pop art sensibilities—his canvases include Ben-Day dots like those used by the artist Roy Lichtenstein and a colorful, screen print style evocative of Andy Warhol. However, he embraces a sense of sentimentality and intimacy that Pop Art traditionally forgoes. Many of his images are whimsical and warm, portraying spaces where a sense of community forms. Summer Cypress (2022) depicts just this sort of gathering. The shading of the screen-printed figures contrasts with the flat colors applied in acrylic paint, creating visual intrigue and a sense of depth, albeit a sort of illogical depth further emphasizing the timeless quality of the image.

A group of three stand together at the center of the image around a pile of what appears to be packages, a man lounges on a bright orange blanket in the bottom left foreground, and a boy enters from behind a tree looking like he just went for a summer-time swim. Behind them, a crowd of anonymous people, silhouetted in blue, mingle in what looks like a park shelter. These elements come together to form an animated and social scene that looks like it could pick up right from where it paused at any moment.

An installation view of Kristopher Wright’s exhibition Just As I Am at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art. Image by Maggie Sava.

While evoking the past, with the figures from the found photographs sporting vintage hairstyles and clothing, Wright moves beyond a simple sense of nostalgia and instead practices something akin to what Christina Sharpe identifies as “beauty as a method.” As Sharpe describes it, beauty as a method entails a looking at the mundane and the everyday with an “attentiveness whenever possible to a kind of aesthetic that escaped violence whenever possible.” [6]

It is not unsurprising that Wright describes his work as “places of sanctuary” where “gratitude, togetherness, and inclusivity” meet. [7] In Just As I Am, Wright accomplishes quite a feat of forming dynamic portals of connectivity and memory through a well-developed and distinctive style, establishing this show as an outstanding solo debut for the artist.

An installation view of Erin Hyunhee Kang’s exhibition A Home In Between at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art. Image by Maggie Sava.

Walking upstairs into BMoCA’s final gallery space, our ears are met with the steady thrumming of the soundtrack to Erin Hyunhee Kang’s exhibition A Home In Between. Throughout the room, projectors illuminate the walls with Kang’s grayscale digital drawings showing homes in various states of peril or destruction. In this series, Kang tackles a collectively and, simultaneously, profoundly personal traumatic event: the Marshall Fire that destroyed over 1,100 homes and businesses in Boulder County from December 30, 2021 through January 1, 2022. Kang’s own home, which was severely damaged during the fire, became a focal point of her exploration of loss. Collaging documentational photographs from areas affected by the fire, Kang creates ghostly, and at times almost nightmarish, landscapes. [8]

Erin Hyunhee Kang, A Home in Between, Partial B: Disappearing from everything and everyone, 2022, digital drawing projection. Image by Maggie Sava.

In A Home In Between, Partial B: Disappearing from everything and everyone (2022), Kang depicts a house standing alone in snow-covered woods, seemingly flickering or wavering into existence right above a pond of water. Through the irreality of a house floating over water, Kang creates a liminal scene where the etherealness emphasizes the “inbetweenness” underpinning this series of works. [9] The fact that it is immaterial (being shown just through the light of the projector on the wall) further emphasizes its ephemerality.

The investigation of the idea of home builds upon the ongoing theme in Kang’s work of diasporic spaces as places of tension where dichotomous experiences converge and coexist. This examination of home and identity connects with her personal experience, having moved from Korea to the United States as a teenager. [10] Landscape is a rich and complicated subject matter, for it becomes “superimposed and conjoined in the inner life of the individual'' experiencing diaspora, as philosopher Nadia Yala Kisukidi notes, evoking the sense of a duality of inhabitation. [11]

The displacement of those who lost their homes in the Marshall Fire, which greatly altered the local landscape, disrupted a sense of comfort or security around the sense of home and inhabiting, leaving instead a great sense of collective and individual anxiety. Questions of what home means, where home is, and if people can return home, persist for those who continue to recover from devastating losses brought on by the fire, the artist included.

A drawing from Erin Hyunhee Kang’s series My child’s walk home to school, 2022, rubbing, image transfer, and graphite on paper, 18 x 24 inches. Image by Maggie Sava

Kang makes the anxiety caused by the massive destruction of the fire palpable in her series of drawings hung in the corner of the gallery, titled My child’s walk to school. They too depict architectural forms in shambles or decay—glimpses of deterioration that, as the name suggests, mar Kang’s neighborhood with reminders of what was lost. The drawing on the far-right end at first looks like a dark puddle or smoke cloud, but upon closer inspection we see intricate details of crumbling brick and broken pipes. The level of detail and patience suggest a deep meditation on these forms not just as physical but psychological presences in what was once home.

A detail view of a drawing from Erin Hyunhee Kang’s series My child’s walk home to school, 2022, rubbing, image transfer, and graphite on paper, 18 x 24 inches. Image by Maggie Sava.

Kang’s works in A Home In Between are visually stunning and almost surreal, delving into a raw and emotionally challenging event. Through her dream-like imagery, Kang provides a space of ambiguity and openness needed to explore loss and despair. However, Kang also wants this exhibition to be a way to seek hope, making her home, as she describes, a place “where healing, reconciliation, and forgiveness could take place in the midst of anger, sorrow, and loss.” [12] Even the soundtrack of the exhibition echoes this—the hammering and sawing are the actual sounds of her home being rebuilt, suggesting a forthcoming renewal.

Though fully able to stand on their own, BMoCA’s fall exhibitions come together to create an expansive exploration of the material, narrative, and emotional potential of photographs. Moving from woven works to large scale screen print-painting combinations to digital drawing projections, these three exhibits display an impressive range of content and form while remaining in conversation with one another. All four artists successfully turn the notion of the mundane on its head, creating new pathways for engagement with familiar (or defamiliarized) images. Altogether, the full program is truly an impressive accomplishment by the museum’s exhibition team and the contributing artists.

Maggie Sava (she/her) is an art historian and writer based in Denver. She holds a BA in Art History and English, Creative Writing from the University of Denver and an MA in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths, University of London.

[1] Writer Rebecca Morse explains how an awareness of materiality and the physicality of canvases goes back at least to Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock, and iterates that artists have used photographic grids to add “dimension into a traditionally flat medium.” Rebecca Morse, “Photography/Sculpture in Contemporary Art,” American Art 24, no. 1 (2010): 31–34, https://doi.org/10.1086/652741.

[2] C-prints, or chromogenic prints, are chemically sensitive to environmental elements, meaning that they are more susceptible to fading and loss of visual quality. “C-Print,” Tate, accessed September 29, 2022: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/c/c-print.

[3] Kevin Hoth, “Immortal Chromatic,” accessed September 25, 2022: https://www.kevinhoth.com/#/immortal-chromatic/.

[4] Ibid.

[5] From the exhibition text.

[6] Christina Sharpe, “Beauty Is a Method,” e-flux Journal 105 (December 2019): https://www.e-flux.com/journal/105/303916/beauty-is-a-method/.

[7] From the exhibition text.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Nadia Yala Kisukidi, “Geopolitics of the Diaspora,” e-flux Journal 114 (December 2020): https://www.e-flux.com/journal/114/364962/geopolitics-of-the-diaspora/.

[12] From the exhibition text.