Nepantla

Nepantla

Museum of Art Fort Collins

201 S. College Avenue, Fort Collins, CO 80524

October 4, 2024–January 5, 2025

Curator: Tony Ortega

Admission: Adults: $10; Seniors: $8; Educators: 50% off; College Students, Military and Veterans, Museum Members, and Visitors Under Age 18: free

Review by José Antonio Arellano

I knew I would make the pilgrimage to the Museum of Art in Fort Collins when I heard that Tony Ortega had curated an exhibition there. Comprising the work of thirty-six artists from Colorado and New Mexico, the exhibition invites its viewers to consider the continued relevance of the Nahuatl term “Nepantla,” which Gloria Anzaldúa helped circulate in 2002.

A view of the title wall and part of the exhibition Nepantla at the Museum of Art Fort Collins. Image by DARIA.

During the 1980s, Anzaldúa periodized the Mexican American civil rights activism called the Chicano Movement. [1] Although she recognized the importance of Chicano activism, she critiqued its gendered exclusions and instead placed queer women of color at the forefront.

Rather than advancing decolonial images of Mesoamerican iconography, as had many of the previous generation’s Chicano artists, Anzaldúa developed more liminal concepts, including the metaphor of the “borderlands” (in 1987) and “Nepantla” (in 2002). In an essay that serves as her last edited collection’s preface, Anzaldúa writes:

Bridges span liminal (threshold) spaces between worlds, spaces I call nepantla, a Nahuatl word meaning tierra entre medio [in between land]. Transformations occur in this in-between space, an unstable, unpredictable, precarious, always-in-transition space lacking clear boundaries. Nepantla es tierra desconocida [is unknown land], and living in this liminal zone means being in a constant state of displacement—and uncomfortable, even alarming feeling. [2]

An installation view of the exhibition Nepantla at the Museum of Art Fort Collins. Image by DARIA.

Nepantla thus names a more dizzying conceptual space that contrasts with the mythic origin narratives Chicanos had previously advanced. These stories, including that of Aztlán, the mythic homeland of the Aztecs located somewhere in the American southwest, had helped to fortify the Chicano identity. Reclaiming Aztlán could mean the reclamation of the land first stolen by Spanish colonialism and then American imperialism, and it could be understood as a decolonial bulwark against existing caricatures of Mexicans and Mexican Americans.

An installation view of the exhibition Nepantla at the Museum of Art Fort Collins. Image by DARIA.

Nepantla, though, is the space in-between this land-based metaphor, allowing for an identity that is more fluid, more “hybrid” (as it was called in postcolonial theory), or more intersectional (as we tend to say today). [3]

In several works that make up this exhibition, the concept of “identity” feels simultaneously assured and precarious—in the process of becoming. The assuredness is based on the genealogies of ancestry and culture that provide the idioms for one’s self-fashioning. Yet a shaky feeling arises with self-fashioning when the basis of an identity comes under question.

Diego Florez-Arroyo, Neplantacoatl, 2024, concrete and structural mortar, 18 x 9 x 4 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Diego Florez-Arroyo depicts a segmented sculpture of the plumed serpent Quetzalcoatl, “one of the great gods of ancient Mesoamerica.” [4] While seemingly paying homage to the ancient deity, Florez-Arroyo depicts the sculpture as a precariously stacked column capable of being toppled. He deconstructs the sculpture and, with it, the belief system upon which it is built.

The ideological basis of an identity enabled by this belief system would remain available if one were to bolster the sculpture through structural reinforcement. The segmented rectangular forms, though, also appear as stack-and-build blocks with which the beholder could construct something new, rearranging the pieces at will.

Josiah Lee Lopez, Creation Lot 20, 2023, acrylic, marker, and archival ink pen on recycled paper, 48 × 48 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Josiah Lee Lopez’s Creation Lot 20 also provides the sense of the inchoate potential made possible through the deconstruction of Mesoamerican iconography. Reminiscent of paño arte (the “intricate ink or pencil drawings on handkerchiefs created by incarcerated Chicanos”) [5], Creation Lot 20 depicts the Aztec calendar stone “in its early stages of creation,” as Lopez puts it, existing in a state of “discombobulation.” [6]

The image, I want to suggest, portrays something like the dialectic of being and nothingness confronting each other. The “being” of the deconstructed Aztec calendar stone appears in a state of potential, confronting a black void of seeming nothingness. This void, however, contains a universe of stars that materializes into a substance that seeps upward. Or, perhaps, the substance flows down from the deconstructed icons, creating the void itself. This dialectical tension depicts the state of becoming that sublates both possibilities.

Juan Fuentes, Home Won’t Know Me, 2021, inkjet photographic prints, 36 x 24 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

In the self-portrait titled Home Won’t Know Me, Juan Fuentes blurs his face by moving it faster than the camera’s shutter can capture. Fuentes’s identity appears in flux; his blurred face disrupts the recognition that his surrounding society may never have granted him. Yet, he holds another photograph that shows his grandfather as a younger man.

This photograph might serve as a facial substitute, a potential basis for Fuentes’s sense of self. He holds on, as we tend to say, for dear life. An embroidered handkerchief (a pañuelo) hung behind Fuentes’s blurred face functions as a framing anchor. This handkerchief reappears in the adjacent photograph titled Deteniendo Los Años (my translation is Holding the Years), in which his grandmother wears it around her neck.

Juan Fuentes, Deteniendo Los Años and Home Won’t Know Me, 2021, inkjet photographic prints and scarf, photographs: 36 x 24 inches each. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

His grandfather also reappears in this photograph, standing upright and resolute, yet time is now visible on his face as it had not been in the photograph Fuentes holds. Both of Fuentes’s photographs thus capture moments that signal the absence that awaits us all—the ensuing pain which might only be redeemed through the memory of the love we have received.

As if desiring to hold on to what time will inevitably take, Fuentes hangs the actual handkerchief onto the upper left-hand side of the photograph’s frame. The handkerchief appears as an emblem of a desire to make present what a photograph can only make visible.

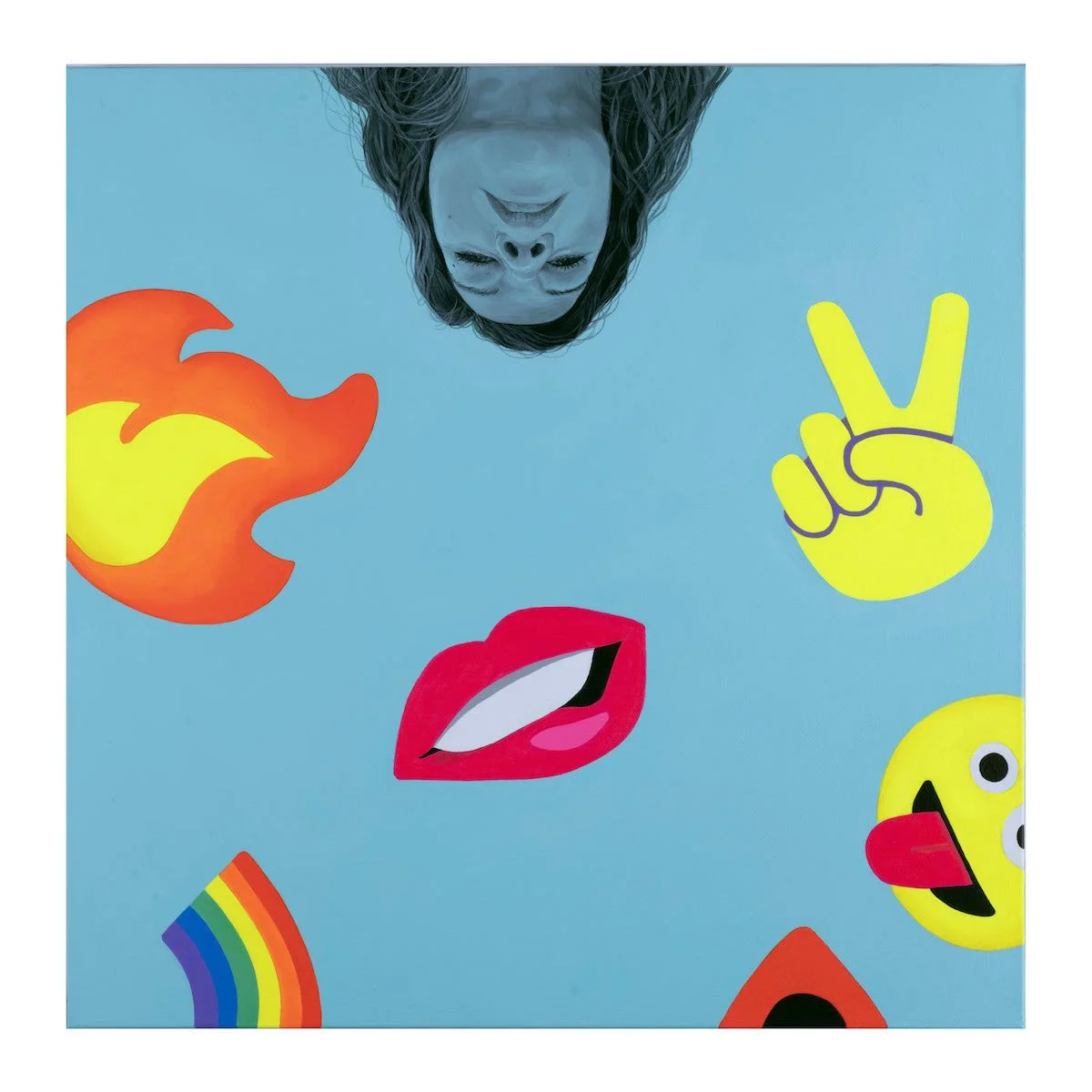

Verónica Herrera, I Feel Seen, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 25.5 x 25.5 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Verónica Herrera’s diptych I Feel Seen captures the dynamic of self-regard that betrays a desire for social recognition. The emojis capture the simultaneously meaning-laden and substantively bereft communicative mode of our era.

“Icons” are defined broadly by Scott McCloud as “any image used to represent a person, place, thing, or idea.” [7] Icons are mimetically contagious, epidemically circulating through the virality of memes, because they so efficiently embody a world of emotions. Yet they are also substitutes that mask a more dire reality. (“LOL,” I type with a stone serious face.)

An installation view of the exhibition Nepantla at the Museum of Art Fort Collins. Image by DARIA.

The diptych captures the dynamic of an aesthetic experience between the work of art that judgmentally knows more than the beholder (whose interpretations will always fall short), and the beholder looking up at the work of art with great expectations. Is an experience of interpretive plenitude possible, or are we always caught in the maelstrom of signs that conceal more than they purportedly express? What role, then, can art play in our age?

While profoundly serious, this examination of self-identity is also irreverently playful, a sense of play visible in the artist Alfredo Cardenas’s self-description as “un-Americano.” Using English and Spanish simultaneously, Cardenas adds the gender suffix “o” to the noun “American” and a hyphen between “un” and “Americano.” [8] In English, the prefix “un” modifies a word's meaning negatively, but in Spanish, the word “un” is the indefinite article meaning “a” or “an.” Some may perceive Cardenas as “un-American,” not fitting a false, mainstream conception, yet he remains an American. He is, in his words, “Chicano.” [9]

Alfredo Cardenas, Cruzin’ La Grande Jatte in My Classic Chevrolet, 2023, mixed acrylic on Masonite and found art, 20 x 37 x 3.5 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Cardenas’s Cruzin’ La Grande Jatte in My Classic Chevrolet continues this playful hybridity in visual, art historical terms. The shaped Masonite support reminds me of Frank Stella’s experimentation in his Damascus Gate variations from the 1970s. Yet, in Cardenas’s hands, this experimentation with shape is transformed into the window of a “ranfla,” slang for car. [10]

The painting’s conceit situates the car and its driver (dressed in the characteristic garb of the cholo) within the post-impressionistic world of Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884-86). [11] Cardenas demonstrates his comfort within Seurat’s visual language, but he insists on using it in on his own terms.

If Seurat’s method of placing complementary dabs of paint colors alongside each other enables the viewers’ eyes to blend the hues visually, Cardenas’s use of point/counterpoint is instead a metaphor for the juxtaposition of the styles on display. The flannelled arm casually slung out of the car’s window exceeds the painting’s framing effect, as if Cardenas refuses to allow his figure to be contained by the space of art, or by art history itself.

Sylvia Montero, Danza de La Nepantla, 2024, acrylic and collage on panel, 44 x 36 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Art history is also in play in Sylvia Montero’s Danza de La Nepantla, which references Matisse’s iconic cut-out Icarus. Matisse started to develop his “cut-out” technique while working on stage sets and costumes for Serge Diaghilev’s ballet company Ballets Russes. His Icarus, like Montero’s Nepantla, appears to be dancing—not falling. Whereas “drawing with scissors—cutting directly into colored planes” allowed Matisse to resolve what he perceived as a “conflict between drawing and painting,” Montero instead maintains the “conflict” of media depicted as content. [12]

Montero uses collage on a background of acrylic brushstrokes and depicts her figure with a Mesoamerican glyph on its chest instead of a red heart (as had Matisse). To my eyes, this glyph appears to name the powerful Mayan goddess Chak Chel. [13] The Aztec water goddess Chalchiuhtlicue (“she of the jade skirt”) also appears in Danza in the form of the colossal sculpture found in Teotihuacan, Mexico. Whereas Icarus is surrounded by yellow stars, Montero overlays yellow stars onto her figure as if to situate the source of celestial power within the dancer herself.

Tony Ortega, Nepantla, 2024, woodcut, 35 x 49 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Tony Ortega also invokes Mesoamerican iconography with his woodcut Nepantla, referencing the clay stamps developed in ancient Mexico, studied by the Mexican illustrator Jorge Enciso. In 1947, Enciso published an influential book Sellos del antiguo México in which he reproduced the designs made from ancient clay stamps. The “stamping process was frequently used to decorate pottery, “writes Enciso, “applied to the surface of the vessel when the clay was still pliable.” [14] Inked stamps were also used on “cloth or paper.” [15]

The process of producing Nepantla also echoes the Mayan sculptural creation of the glyphs (included behind the “cholo” figure) and the glyphs’ archeological recording. The act of carving and inscribing was uniquely significant in the Mayan world and visible on public-facing stone stelae and panels. [16] The process of “rubbing” these inscriptions became a method for archeologists to record the Mayan glyphs. [17]

Ortega introduces more contemporary icons into the Mesoamerican vocabulary, including an image of a lowrider and two central figures depicting a Mexican “soldadera” and a Chicano “cholo.” The term “cholo” invokes a complicated history, encompassing 20th century Mexican American counterculture and a derogatory Spanish caste designation (see endnote 11).

An installation view of the exhibition Nepantla at the Museum of Art Fort Collins. Image by DARIA.

In the race-obsessed Spanish caste paintings, called “castas,” “cholo” refers to the child of a “mestizo” (a person of half Spanish and half Indigenous descent) and an Indigenous person. The term may have originated from the name of a hairless dog species native to Mexico, the Xoloitzcuintli (“Xolo” for short), often invoked in Aztec mythology. In Nepanlta, however, the Cholo stands proud alongside the “soldadera,” a woman who fought during the Mexican Revolution identified by the bandoliers worn across her chest. Ortega superimposes the image of the Soldadera onto that of the Virgen de Guadalupe, itself a complicated hybrid of Indigenous and Spanish religious iconography.

This temporal superimposition of Mayan and Aztec iconography, Mexican revolutionary symbols, and contemporary Chicano symbols (including a lowrider “ranfla”), implies a postmodern historicism in which the past appears alongside the present. Such ahistorical historicism (simultaneously in history and transcending it) has been characteristic of Chicana/o scholarship that establishes a long legacy going back centuries. [18]

Emanuel Martinez, Nepantla, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 30 x 40 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

This centuries-long legacy is visible in the symbolic symmetry of Emanuel Martinez’s painting Nepantla, which signifies the unity of multiple dualities: male and female, European and Indigenous, and lighter and darker skin. The painting’s center depicts the process of fertilization that opens to a dual vitalism in embryonic form. Two hands hold spheres, alluding to what reproductive biologists call the “gonadal regions” that can become testicles or ovaries, here represented in stasis before their development. This binarism, though, merges to create a tri-faced figure representative of the Chicana/o identity. A pinkish-violet color connects the sexual organs to the tri-faced figure, visually making available the potential for queering binaries.

The complex symbolism rests on the back of a life-sustaining turtle, a significant symbol in Mayan iconography. A green feathered serpent encircles the two human figures, almost creating an Ouroboros-like cyclicality, yet the reference here is distinctly Mesoamerican: the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl.

Although there are similar double-faced figurines in ancient Tlatilco, Mexico, the first instance of the tri-faced symbol I recall studying appears on Emanuel Martinez’s Farm Workers’ Altar (1967) that he made for Cesar Chávez. The altar was used when Chávez broke his hunger strike, which was meant to draw attention to labor conditions in California. The symbol became a repeated motif, visible in well-known Chicano art, and used by other artists included in this exhibition.

Sean Trujillo, The Sacred Unity, 2024, pigments from Colorado and New Mexico, pine wood, marble dust, rabbit skin glue, and gesso, 24 x 14 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Sean Trujillo for example, includes the symbol in the retablo The Sacred Unity. The tradition of this type of devotional painting dates to the eighteenth-century New Mexican religious folk art made by “santeros.” Thomas J. Steele provides a useful, descriptive definition of the “retablo,” defined as “a painting made on a pine panel, sawed at top and bottom, the rest split or sawed or hand-adzed and the front smoothed, covered with gesso (a mixture of gypsum and animal glue) and painted with water colors, many of them homemade from carbons, earth oxide, and organic substances, some made from dyes imported into the colony.” [19]

Trujillo maintains this tradition, including its Christian symbolism. Yet, whereas the New Mexican santero tradition valued the imitation of Christian personages—“a painting was judged holy if it repeated the previous paintings of the same subject in its tradition”—Trujillo instead introduces Chicano iconography into the Christian trinity symbolism. Chicanos, here, are a sacred people.

Lizeth Guadalupe, La Conciencia De Una Mestiza, 2024, textiles, each apron 38 x 25 x 1 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Lizeth Guadalupe provides a more conceptual take on the three-faceted symbolism with aprons representative of gender norms of domesticity and propriety. The subtle color shift symbolizes the merging of two worlds, a tanner color to the left and a lighter white to the right, meeting in the central apron, representing the merged “mestiza” consciousness.

Carlos Frésquez, Nepantla, 2024, acrylic on unstretched canvas 9 x 6 feet. Image courtesy of the artist.

Carlos Frésquez depicts the merger of Spanish and Indigenous peoples as embodied in the figures of Hernan Cortez and La Malinche. [20] Frésquez offers a layered approach to this common theme, depicting the legacy of Spanish colonialism and Indigenous symbolism through the accumulation of paint that creates the outlines of meaning.

I am reminded of Walter Benjamin’s description of the “storm” of so-called “progress,” wherein the violence of history accumulates, piling wreckage upon wreckage. In this painting, history appears stenciled on top of itself while the deathly grin of a calavera serves to clothe the mestizo child who personifies the birth of the Mexican people.

Armando Silva, Mito, 2024, acrylic and aerosol painting on canvas, 5 x 4 feet. Image courtesy of the artist.

Armando Silva also takes a layered approach in Mito, combining vibrant aerosol paint sprayed onto acrylic to represent a man in the middle of putting on or taking off a mask. An explosion of color surrounds the figure, at points coalescing to suggest various flora, including cacti and prickly pears. Whatever the relationship between the man and mask might be, he appears connected to it via the cactus spines that grow out of his arm and mask. This detail reminded me of the Spanish expression, “Tienes el nopal en la frente” (“you have the cactus on your forehead”), referring to someone who unsuccessfully pretends not to be “Mexican” (however defined). [21]

Emilio Lobato, Charco (Puddle, Ripple Effect), 2024, oil and collage on panel, 36 x 36 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Emilio Lobato offers a decolonial intervention into the cartographic drive that aids colonization and exploitation. In Charco (Puddle, Ripple Effect), black voids create ripples as if indicating the potential effects of what could have been, the unknown intervening into the topographical imagination that seeks to map and thereby potentially know and control every part of the world. Just as maps enable discovery and conquest, these voids suggest both constructive potential and insidious destruction—the extractive effects of human intervention.

This duality of construction and de(con)struction, of enabling an identity and exposing its foundations, animate so many of the works of art included in this exhibition. The works could function as the precarious, shifting basis on which a collective identity can see itself as itself. This is the circular logic of this kind of art: a people coming to recognize themselves as a people via the development of art that reflects their identity by creating it.

An installation view of the exhibition Nepantla at the Museum of Art Fort Collins. Image by DARIA.

The tautology could reify an essentialism that should give us pause. For, after all, what makes these works of art part of my story more than any other work of art? And yet, when my family and I moved to Colorado Springs in 2019, Tony Ortega’s painting Aztlán (1992) appeared to welcome me at the Colorado Springs Fine Art Center. That same day, Emanuel Martinez’s mural Arte Mestiza (1986) also seemed to speak to me.

What I heard that day was a saying that Chicanos, Chicanas, and Chicanxs have collectively declared for decades: However you want to say it, whatever this means today, we know this to be true, tu y yo somos Chicanos. Many of the works in this collection extend such an invitation. It remains up to the viewers to decide whether they will accept it.

José Antonio Arellano (he/his) is an Associate Professor of English and fine arts at the United States Air Force Academy. He holds a Ph.D. in English language and literature from the University of Chicago. He is currently working on two manuscripts titled Race Class: Reading Mexican American Literature in the Era of Neoliberalism, 1981-1984 and Life in Search of Form: 20th Century Mexican American Literature and the Problem of Art.

[1] “What you could say is that in the sixties and the early seventies the Chicanos were at the controls,” she described in an interview, “They were the ones who were visible, the Chicano leaders. Then in the eighties and nineties, the women have become visible... names like Cherríe Moraga, Gloria Anzaldúa and other Chicana authors... So it—the Chicano Movement—has shifted into the Movimiento Macha.” Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 1987), 229.

[2] Gloria Anzaldúa “(Un)natural bridges, (Un)safe spaces,” This Bridge We Call Home: Radical Visions for Transformation. (Routledge, 2021), 1.

[3] See José F. Aranda, When We Arrive: A New Literary History of Mexican America (University of Arizona Press, 2003), 34-36.

[4] Mary Ellen Miller and Karl A. Taube, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya (Thames and Hudson, 1997), 141.

[5] Álvaro Ibarra, “The Private Life of Paño Arte,” Hyperallergic, 23 Feb. 2024, hyperallergic.com/869813/the-private-life-of-pano-arte/.

[6] Exhibition catalog, 21.

[7] Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (Harper Perennial, 1994), 27.

[8] Exhibition catalog, 4.

[9] Ibid.

[10] According to Rubén Cobos a “ranfla” refers to a “Rambler (American Rambler)” and is slang for “auto, car.” “Ranfla,” Ruben Cobos, A Dictionary of New Mexico & Southern Colorado Spanish (Museum of New Mexico Press, 2003), 195.

[11] According to Rafaela G. Castro, “cholos” are “Young Chicano males… who are distinguished by the clothes they wear, their speech, gestures, and a defiant street style…. Although the attire of cholos varies from barrio to barrio, many wear baggy khaki pants, white tee shirts, and plaid Pendleton shirts…” “Cholos,” Rafaela Castro, Dictionary of Chicano Folklore (ABC-CLIO, 2000), 61.

[12] The first quotation is by Matisse, the second is by Katrin Wiethege, both found in Katrin Wiethege, “Matisse: The Paper Cut-Outs,” Jazz (Prestel, 2001), 10.

[13] See Michael D. Coe and Mark Van Stone, Reading the Maya Glyphs (Thames & Hudson, 2001), 117.

[14] Jorge Enciso, Design Motifs of Ancient Mexico (Dover Publications, 1993), v.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Although Mayans considered writing and painting as “virtually identical,” they did “distinguish between the scribe who used the brush pen and the scribe who carved or incised texts and scenes.” Coe and Van Stone, 13-14.

[17] Merle Green Robertson employed various processes of rubbing to record the Mayan glyphs. See her essay "Classic Maya Rubbings," Expedition Magazine 9, no. 1 (September, 1966), https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/classic-maya-rubbings/.

[18] Responding to the question who are the soldaderas, Elizabeth Salas writes, “they were both Mexican army women and Chicanas living in the United States,” also adding a history of “soldaderas in Mesoamerican warrior societies and their mythification in religion as war goddesses,” Elizabeth Salas, Soldaderas in the Mexican Military: Myth and History (University of Texas Press, 1990), ix.

[19] Thomas J. Steele, Santos and Saints: The Religious Folk Art of Hispanic New Mexico (Ancient City Press, 1994), 26.

[20] As the folks who visited the exhibition Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche at the Denver Art Museum were able to see, there are dozens of such depictions, https://www.denverartmuseum.org/en/exhibitions/malinche.

[21] In the exhibition catalog, Silva describes being influenced by his father, who is involved in the ceremonial dances performed in the town of Sombrerete in Zacatecas, Mexico. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SJnlZrLpC7E. I am not familiar with this particular mask, but it resembles the attributes of the god Tlaloc. If you click on this link https://www.amazon.com/Ancient-Mexican-Costume-W-Solier/dp/B000INXBJ6], scroll to the second image for a depiction of a similar Tlaloc mask by W. Du Solier.