Art Student and Alumni Invitational

Art Student and Alumni Invitational

Colorado Gallery of the Arts, Arapahoe Community College

5900 S. Santa Fe Drive, Littleton, CO 80120

March 23–May 5, 2023

Admission: Free

Review by Vanessa Kauffman Zimmerly

Artmaking is the pursuit of expressing our inner life through metaphorical and material means. [1] At the Arapahoe Community College Art Student and Alumni Invitational, on view now at the Colorado Gallery of the Arts on the Littleton campus, ten artists bring their ideas into being through drawing and painting, installation, metalwork, photography, sculpture, and textiles. The premise that materiality holds meaning is what connects them.

An installation view of the Art Student and Alumni Invitational exhibition at the Colorado Gallery of the Arts at Arapahoe Community College. Image by DARIA.

Anthony Snyder’s Untitled series, 2023, Holga film images printed in the darkroom as a silver gelatin photographic prints. Image by DARIA.

Transposing the dream world to the waking world is the project of Anthony Snyder. He shot his photographic series with a Holga camera and printed it in the dreamscape of the photo realm: the darkroom. In Snyder’s seven square, black-and-white images, the ambience of somnolence merges with recognizable depictions of a forest, bodies of water, land masses, and sky.

Anthony Snyder, Untitled, 2023, Holga film image printed in the darkroom as a silver gelatin photographic print. Image courtesy of Arapahoe Community College’s Colorado Gallery of the Arts.

Visual manipulations of the images that impinge on clarity—such as blur, repetition, and mirroring—offer insight instead of confusion. Snyder uses them to mimic the twists our subconscious mind makes while sleeping, revealing, as he writes, “the secrets that we have kept from ourselves.” [2]

Nicole Hartman’s series Lost: An Evolution of Emotion, 2023, fine art pigment prints. Image by DARIA.

Nicole Hartman also explores emotional veils and the evolution of lifting or exposing them. Her portrait series Lost: An Evolution of Emotion comprises five photographs, each capturing a different stage of the self as it experiences betrayal, depression, dissociation, isolation, and finally, reawakening.

Nicole Hartman, Split, 2023, fine art pigment print. Image by DARIA.

The human face takes center stage in these images and Hartman alternately elucidates or obscures it with the elements of water and light. Combined with these ephemeral, atmospheric materials, the gaze oscillates between direct and avoidant, open and private, showing the real fluidity of emotional states within the perceived solidity of personhood.

Four works from Cindy Young’s Life series, 2023, black and white film photography printed in the darkroom as silver gelatin photographic prints. Image by DARIA.

Turning from a focus on the self, in Cindy Young’s Life series, the artist intimately documents her daughter Ava’s everyday life as a young person with Down syndrome. Utilizing traditional film photography in a monochromatic, black-and-white palette, Young places the visual focus on Ava—who is most often positioned in the middle of the frame—and the emotion present in each moment. By showing Ava in a wide range of activities and bearing a variety of dynamic expressions, Young is resisting assumptions that seek to flatten individuals due to disability.

Sisel Lan, Kal from the series Portraits in Confinement, 2023, installation with photography. Image by DARIA.

Large-scale installations by Jodee Sweet and Sisel Lan are situated on opposite walls of the gallery. Both works utilize sizable swaths of material with which viewers can intervene. Lan’s piece, Portraits in Confinement, shows the spatial discrepancy between the area various animals are given at the zoo versus what they inhabit in nature. The artist displays individual photographs of four animals, taken with a toy camera and self-made telephoto lens, in framed glass boxes scaled to match their confinement size.

Sisel Lan, Portraits in Confinement, 2023, installation with photography. Image by DARIA.

Behind and flowing onto the floor below the frames are lengths of white paper representing the size of the species’ natural habitats. Engaging with the piece requires indelicately traipsing across the makeshift paper wilderness, scuffing and crumpling it and making an audible soundtrack that breaks the gallery’s quiet. It’s impossible not to ask: Is it possible to tread lightly when it comes to zoology and conservation?

A detail view of Jodee Sweet’s Nihilism, 2023, installation, paint, and plastic, 16 x 42 feet. Image by DARIA.

In Sweet’s piece titled Nihilism, the artist has built up a wall with expressive gestures of paint, handwritten text, and many layers of plastic wrap that together build a “spoiled skin,” as the artist calls it. [3] Naming imposter syndrome and self-grief as the impetus for the piece, Sweet invites viewers to interact with the metaphorical body by ripping or pulling through it. As a result, chips of paint and thread-like pieces of plastic pool up on the floor below, literally debased and disembodied. Unlike a skin, however, this piece does not regenerate more of itself. As it transfigures, it more closely resembles the state of our interior—becoming weathered, worn, and indurate through life experience.

Amy Mower, Rotko Neck Piece, 2023, sterling silver, 22-karat chrysoprase, spiny oyster, and enamel. Image courtesy of Arapahoe Community College’s Colorado Gallery of the Arts.

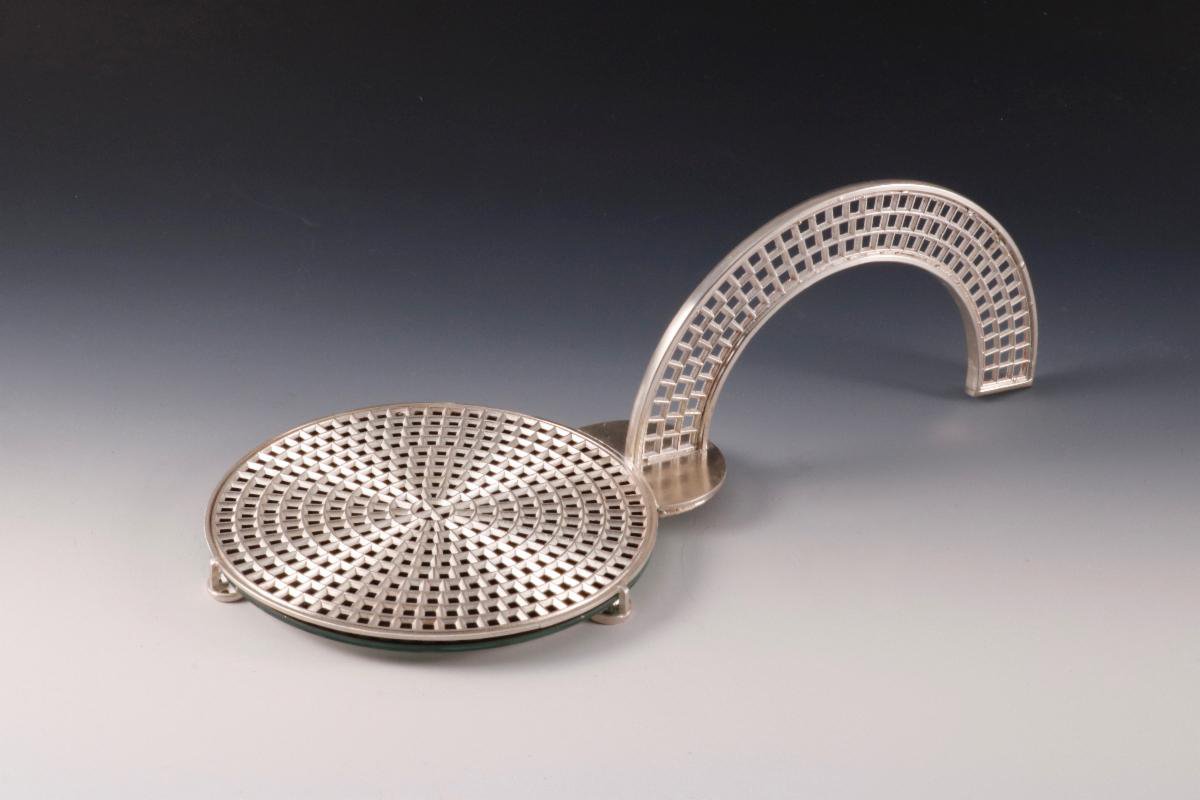

Metalworkers Mary Murphy and Amy Mower attend to what we wear on the skin for purposes of adornment in their jewelry creations and, from Murphy, a set of handheld mirrors. Both artists use fine metals, including sterling silver and 18- and 24-karat gold, in their functional, wearable art. Mower experiments with the ancient global traditions of cloisonné and champlevé. The artist works with inlay and enameling techniques to bring variously colored gems and stones together in pieces that hold delicacy and density at balance.

Mary Murphy, Art Deco Silver Mirror, 2023, sterling silver, mirror, cast, and fabricated. Image courtesy of Arapahoe Community College’s Colorado Gallery of the Arts.

Murphy uses the Korean technique of Keum Boo, where a thin sheet of gold is fused to silver. This Klimt-inspired stacking of mixed metal squares adds nuance, and a trace of texture, to her spare and geometric earrings and pendants.

Andrea Gordon, Becoming Dimensional, 2023, wallpaper, ceramic, and papier-mâché. Image by DARIA.

Andrea Gordon, Pockets (in green), Loopy (in peach, yellow, and orange), Dot (in pink and red), Brainy (in red), and New Language #2 (in black, yellow, and orange), 2023, ceramic and papier-mâché. Image by DARIA.

Using craft in a less precise and precious way, Andrea Gordon has created a mixed-media installation called Becoming Dimensional. Amorphous forms emerge into the third dimension from a wall-sized digital collage. Brightly colored ceramic sculptures, with names like Gingerly, Loopy, and Brains, toe the line between formal precarity and certainty, with many serving as vessels for fabrics that are variously stuffed into or spilling out of their ceramic enclosures.

Amber Seegmiller, Bad Hands #4, 2023, print of watercolor and ink on paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

Amber Seegmiller, Requiem, 2023, ceramic. Image by DARIA.

On the adjacent wall, Amber Seegmiller renders a cosmography of interconnectedness. Her exacting and highly illustrative sculptures and works on paper feature overlapping hands and an oozing bust covered in eyeballs.

A view of Zoe Handler's works in the Art Student and Alumni Invitational exhibition. Image by DARIA.

Zoe Handler addresses ancestral connections through slow, contemplative crafts like weaving and quilting. Her series of five individually titled works is bookended by hands on both sides: on the left is a wall-mounted piece of palm bark that resembles two open hands, while on the right is a pair of cyanotypes that photographically depict the same.

Zoe Handler, These Golden Threads [I], 2023, cyanotype on cotton sateen, cotton linen backing, and metallic thread, 10 x 8 inches. Image by DARIA.

In the latter image, the hands hold something small up to the light, offered as though in prayer. Though the installation incorporates material culture and traditional crafts (one piece is mounted to a loom), Handler employs a subtle poetry of incompletion that leaves gaps in the weave for personal reflection on sentiment and grief.

An installation view of the Art Student and Alumni Invitational exhibition. Image by DARIA.

Arapahoe Community College gallery director Trish Sangelo explains that the ten artists chosen for the invitational were selected because they are in the process of establishing or completing a comprehensive body of work. [4] In most cases, the exhibited work was made with the show in mind—and, at times, created specifically for the gallery space. As a whole, the exhibition is a diverse tapestry with vibrant individual threads that can, and hopefully will, carry on in a multitude of directions.

Vanessa Kauffman Zimmerly (she/her/hers) is a writer and editor. She writes about contemporary art, architecture, design, material culture, and poetics for a variety of publications. She is a regular contributor to Modern In Denver magazine and served as an editorial member of the experimental poetry publisher Kelsey Street Press in Berkeley, California, for several years. Originally from the West Coast, she now lives in Denver with her partner and daughter.

[1] I would argue that to make art is to make the landscape of the mind apparent in the physical world (we describe how art is made with the word “medium,” the same term we use for a spiritual go-between).

[2] Anthony Snyder, artist statement.

[3] Jodee Sweet, artist statement.

[4] From a conversation with Trish Sangelo, Arapahoe Community College Art Gallery, March 24, 2023.