Nature, Flora, Fauna, Earth

Nature, Flora, Fauna, Earth

Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum

200 Violet Street, Suite 140, Golden, CO 80401

January 16–April 15, 2023

Admission: Adults: $8, Seniors: $7, Active Military, Students, and Children 6-12: $4, Children under 6: free

Review by MG Bernard and Maggie Sava

Founded in 1981 to “collect, preserve, exhibit, and educate the public about quilts; honor quiltmaking traditions; and embrace the evolution of the art and craft of quilting,” the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum (RMQM) has become a local hub for dedicated and seasoned quilters as well as those who appreciate the art form. [1] For Nature, Flora, Fauna, Earth, a current exhibition in the Main Gallery, the museum has dug into their own organization’s history.

An installation view of Nature, Flora, Fauna, Earth at Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum in Golden, Colorado. Image by MG Bernard and Maggie Sava.

The exhibition celebrates the upcoming onset of spring by featuring works that visually depict nature—such as flowers, animals, water, and fire—from RMQM’s permanent collection. Shown together are antique quilts from the Sharee and Murray Newman collection as well as art quilts from the Rooted in Tradition collection. [2] While Nature, Flora, Fauna, Earth speaks to enthusiasts of the textile-based art form, it raises questions about the relationship between traditional and art quilting: What do antique and modern quilts have in common? Why place them together in the same exhibition but on opposing walls? What is quilting’s relationship to the art world? And is there a dichotomy between or a multiplicity of traditional and art quilts?

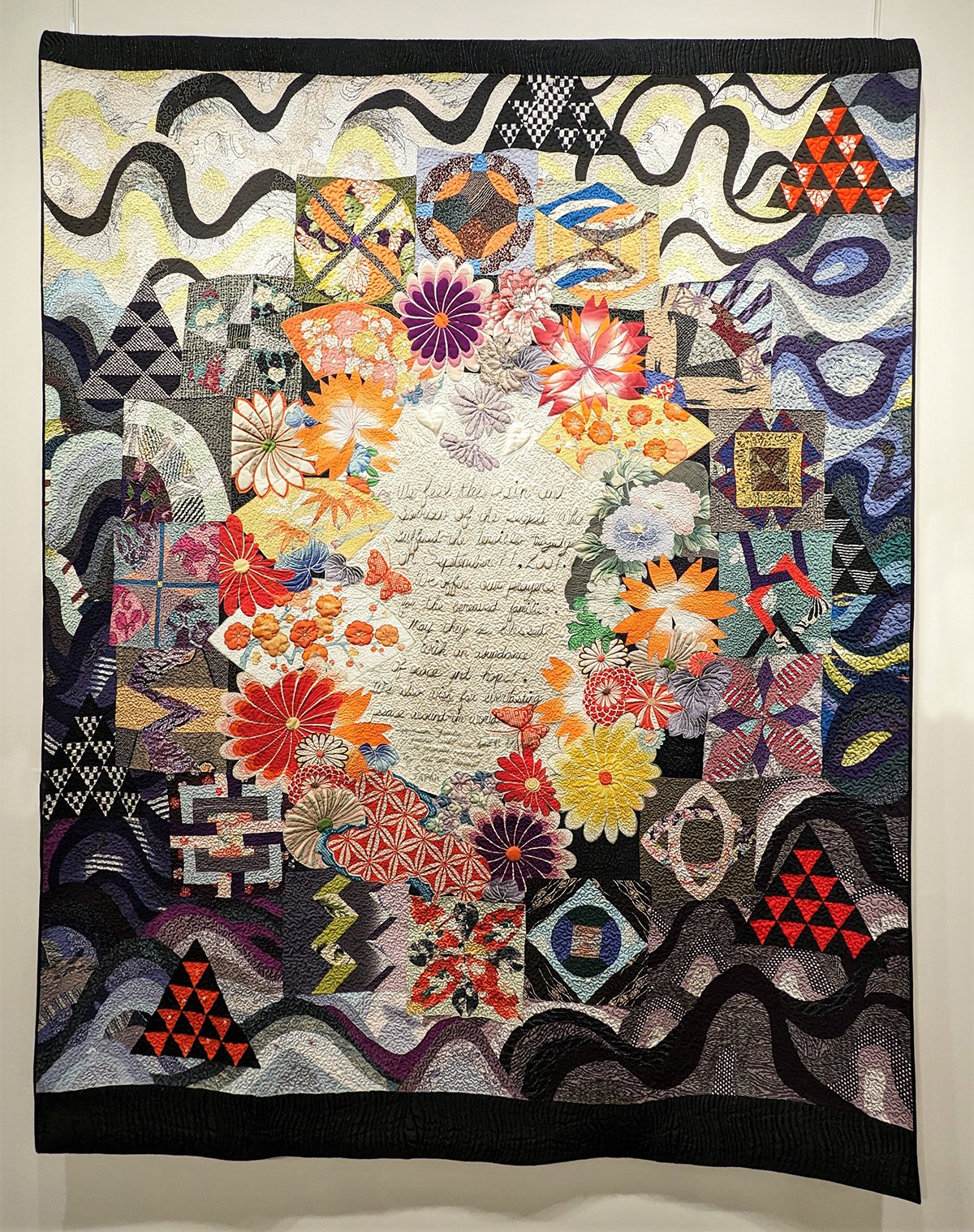

Yasuko Saitoh & Students of Japan, Freedom Quilt, 2001-2002, cotton and silk, machine and hand pieced, hand applique, machine quilted, 75 x 86.5 inches. Courtesy of the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum, Golden, Colorado. Image by MG Bernard and Maggie Sava.

Quilting has always been an integral component of American visual and material culture, embodying both the nation's complicated history and its collective imagination. Before the Industrial Revolution, the expense of cotton and the absence of sewing machines meant the intricate and time-intensive craft of quilting was primarily available to upper-class women. [3] The proliferation of cotton produced by the labor of enslaved people on plantations made fabric more accessible to middle and working-class women and made the craft a more ubiquitous feminine domestic practice. [4] Styles and approaches from this era shaped what is often described as “traditional quilts,” referring to quilts made as functional objects intended to be used in domestic contexts, with similar symmetrical geometric patterns and structures.

An installation view of the traditional quilts in Nature, Flora, Fauna, Earth at the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum in Golden, Colorado. Image by MG Bernard and Maggie Sava.

When viewers enter the Main Gallery at RMQM, they face a long wall filled with examples of large, traditional-styled, 1930s quilts that are instantly recognizable as blankets, each one constructed of two symmetrical, repeating blocks of piecework and fabric appliqués. The quilts’ bold colors, elaborate patterns, and fabrics look soft to the touch and evoke memories of grandma wrapping us up in warm blankets to ready ourselves for sleep. They are each bold and artistic examples that blur the boundaries between private and public. As audience members get closer, they are greeted with intricate, hand-stitched designs of cross hatching, feathered medallions, flowers, and scallop patterning.

Mary Jane “Minnie” Lang Morgan, Dogwood, ca. 1930s, hand and cabled stitched cotton, 77 x 83.5 inches. Courtesy of the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum, Golden, Colorado. Image by MG Bernard and Maggie Sava.

A detail view of Mary Jane “Minnie” Lang Morgan’s Dogwood. Courtesy of the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum, Golden, Colorado. Image by MG Bernard and Maggie Sava.

Towards the back of the gallery on the same wall is Minnie Morgan’s quilt, Dogwood (c. 1930). Unlike several others, Dogwood does not feature individual blocks of fabric, but rather multiple hand-stitched designs across the entire quilt itself. Lying over the hand-stitched designs is a vine or wreath of pink dogwood flowers and leaves individually stitched to the underlying fabric. The flowers are made of needle-turned appliqué with yellow French knots embroidered in the center. [5] Rather than highlighting their conception as artworks, the exhibition celebrates the time-consuming labor and care that went into each quilt’s construction, emphasized by the meticulous technical descriptions on the labels.

On the opposite wall of the gallery, RMQM’s volunteer installation team has created a display of art quilts. As quilt historian Robert Shaw notes, the counterculture of the 1960s, which turned its back on materialism and embraced lifestyles that were in touch with nature, craft, and simplicity, inspired a renewed interest in quilting. [6] The United States Bicentennial coincided with the second-wave feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s also turned attention to the domestic craft of quilting as a source of feminine pride, ingenuity, and skill and, “for the first time, quilts were read as social documents, embodying the history and values of their otherwise silent makers.” [7]

It was during this period that the rise of what would later be called “art quilts” began, sparking a new designation in quilting between traditional practices and aestheticized works incorporating formalized conventions of “fine art.” Despite trained artists working in the quilting medium since the 1930s and galleries and museums displaying quilts in the following decades, many view the 1971 show Abstract Design in American Quilts at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York as the watershed moment for quilts to be appreciated as art objects by the art world at large. [8] The term “art quilt” solidified in the 1980s art vernacular, and artists like Faith Ringgold, who advanced the medium while creating innovative work, gained growing attention and renown.

Nancy Erickson, Hand Shadows, 1995, cotton canvas, commercial fabrics, acrylic paints, machine pieced, and machine quilted, 59 x 61.5 inches. Courtesy of the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum, Golden, Colorado. Image by MG Bernard and Maggie Sava.

Viewers of the art quilts in Nature, Flora, Fauna, Earth are immediately drawn to Nancy Erickson’s Hand Shadows (1995), which looks like a figurative canvas from across the room. As the label describes, Erickson was experimenting with the materiality of her work at the time she made this quilt and approached her pieces less like strict textiles and more like paintings. Audience members can trace the application of acrylic paint on the fabric, Erickson’s painterly strokes underscoring the human and ursine forms. Getting closer, viewers can see how she uses stitching to add dimension and line, as if she is also painting with thread, and incorporates blocks of fabric to designate highlights, expertly combining the two disciplines in her playful composition.

Erickson’s imagery itself is contradictory—the playful nature of making shadow puppets and the relaxed, goofy position of the smaller bear on its back with its paws in the air do not match the impending danger of the landscape on fire, shown outside the window. Is this a warning about the environmental catastrophe of climate change and the loss of habitat? Or could it be a questioning of our connection with the natural world, as the figures sit in an interior scene unaware of the events occurring outside?

Wendy Hill, Falling Into Liquid, 2003, cotton batiks, machine pieced, machine quilted with rayon, metallic, and monofilament threads, 41.5” x 41”. Courtesy of the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum, Golden, Colorado. Image by MG Bernard and Maggie Sava.

Another focal point of the art quilt section is Wendy Hill’s Falling Into Liquid (2003). The large blue circle, like a bullseye, draws the eye and reminds viewers of geometric paintings of modern conceptualist artists like Victor Vasarely. [9] The suggested plainness of the central circle against a square background is disrupted by the intricate and interwoven colors and fabrics. The stitching adds rich texture and movement. Inspired by a story she heard on the radio about surfing, Hills sought to create a visual experience that imitated the experience of falling into water, resulting in a meditative work. Following the circling patterns and stitches can be a contemplative pathway bringing the viewer further into their interior self.

A sewing machine and various irons in Nature, Flora, Fauna, Earth at Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum in Golden, Colorado. Image by MG Bernard and Maggie Sava.

Although some viewers may find a sense of comfort in the traditional quilts and others in the art quilts, the exhibition presents a discontinuity between the two styles. Exhibitions and viewers should not fall into the habit of historicizing “old” art or “craft” while reaffirming a conceptual familiarity and universality of “modern” or “fine art.” Using a feminist lens, many writers have critiqued and broken down distinctions between craft—often a feminized field defined by technique and material—and modern art, which has historically been constructed as a masculine field valued for its conceptual nature.

How can we continue to recontextualize the discourse around quilting to position traditional and art quilts in conversation with one another, both capturing the profoundly personal and public experience of our shared material culture? All in all, RMQM misses the opportunity to place traditional-style and art quilts into conversation with each other and acknowledge the progress made in conversations around craft versus fine art, traditional versus modern, and technique versus concept.

Mary Grace Bernard (MG, she/her) is a transmedia and performance artist, educator, advocate, and crip witch. Her practice finds itself at the intersection of performance art, transmedia installation art, art scholarship, art writing, curation, and activism.

Maggie Sava is a writer based in Denver, Colorado. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Art History and English, Creative Writing from the University of Denver and a master’s degree in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths, University of London. Writing is her main artistic engagement, which she pursues through research, art writing, and poetry.

[1] Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum, “History of the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum,” https://www.rmqm.org/history-of-the-rmqm.htm, accessed January 22, 2023.

[2] The Cambridge Dictionary defines a quilt as “a covering for a bed, made of two layers of cloth with a layer of soft filling between them, and stitched in lines or patterns through all the layers,” https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/quilt, accessed January 22, 2023.

[3] Robert Shaw, “Discovering the roots of the art quilt,” A brief history of the art quilt, reprinted from SAQA Journal (Winter 2014), https://www.saqa.com/sites/default/files/files/SAQA-ShawFeatures.pdf, accessed January 22, 2023.

[4] Melanie Anne Pauls, “Piecing together creativity: feminist aesthetics and the crafting of quilts,” (Dissertation, DePaul University, 2014), 10, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/232966364.pdf, accessed January 22, 2023.

[5] According to Quiltepida, “Needle turn applique is an applique technique in which the raw edges of applique pieces are turned under as the piece is being appliqued [or applied] to the fabric base,” https://thequiltshow.com/quiltipedia/what-is-needle-turn-applique, accessed January 23, 2023.

[6] Robert Shaw, "A History of the Art Quilt," excerpt from The Art Quilt (Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, Fairfield, CT: 1997), http://artofthequilt.com/history%20aq.html, accessed January 23, 2023.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] As Shaw explains, “a number of the colorful and often optically challenging geometric patterns of block-style pieced quilts intersected with later abstract paintings by artists such as Josef Albers, Ellsworth Kelly, Piet Mondrian and Victor Vasarely, and the striking similarities between them were not lost on students of modern art.” Shaw, "A History of the Art Quilt," http://artofthequilt.com/history%20aq.html, accessed January 23, 2023.