To See Inside: Art, Architecture, and Incarceration

To See Inside: Art, Architecture, and Incarceration

Museum of Art Fort Collins

201 S. College Avenue, Fort Collins, CO 80524

January 26–March 17, 2024

Admission: Adults: $10, Seniors 60+: $8, Members, Military, Students under 18, and CSU and Front Range Students: free

Review by Aitor Lajarin-Encina

“All forms of consensus are by necessity based on acts of exclusion.”

Chantal Mouffe [1]

Currently on view at the Museum of Art Fort Collins, To See Inside: Art, Architecture, and Incarceration combines paintings by Colorado-based artist Sarah McKenzie and visual works, a sound art installation, and creative writing by incarcerated artists involved in the University of Denver Prison Arts Initiative (DU PAI). The exhibition provides us with the opportunity to reflect on incarceration culture in the U.S. and the ideological structures that circumscribe it. Through representations in different forms—often created by the inmates themselves—of the prison space, its architecture, and the built environment, we are able to grasp how they impact the minds and bodies of those they “contain.”

An installation view of the exhibition To See Inside: Art, Architecture, and Incarceration at the Museum of Art Fort Collins. Image by Sarah McKenzie.

DU PAI has facilitated a wide range of arts-based programming—both in-person and by correspondence—for people incarcerated throughout Colorado since 2017. Sarah McKenzie has been a teacher and facilitator for the initiative since 2020. When developing this project that engages critically with the prison space, McKenzie prioritized including the work of a variety of incarcerated or formerly incarcerated artists who she met or learned about through her work with DU PAI.

An installation view of To See Inside: Art, Architecture, and Incarceration with Sarah McKenzie’s work. Image by DARIA.

The exhibition gives significant space, visibility, and agency to the work and perspectives of the incarcerated artists—a particularly successful example of a community participatory experience made possible through the arts. [2] It is also the second and expanded iteration of a similar exhibition hosted at the Marion Art Gallery at the State University of New York (SUNY) in Fredonia in the fall of 2022.

Sarah McKenzie, View From the Second Tier (Alcatraz), 2022, oil and acrylic on canvas, 48 x 72 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Mackenzie's paintings are technically astute, precise depictions of different prison exteriors and interiors in Colorado and other states. She focuses on architectural features and interior design, offering us views of meeting areas, corridors, patios, furniture arrangements, façades, security doors, and ultra-narrow windows—all with a great level of detail. View From the Second Tier places the viewer inside Alcatraz prison, in front of a labyrinth of prison bars. From this point of view, we can see the outdoor light, indicating the exterior of the prison, but only through the insurmountable isolation apparatus of the prison architecture.

Sarah McKenzie, Window Blinds (Administrative Segregation Unit, Sterling Correctional), 2022, oil and acrylic on canvas, 36 x 54 inches. Image by DARIA.

Window Blinds depicts the building structures that prevent inmates from having access to any exterior views from their cells while still letting some natural light pass through. This painting points to the fact that when incarcerated, not only do individuals lose the right to free movement but also other privileges like being able to see outside. Isn't this also an architectural feature designed to keep the inmates and the activity inside the facility out of sight from non-incarcerated people?

Sarah McKenzie, Some Days the Sky Is Just a Ceiling (Yard, Sterling Correctional), 2022, oil and acrylic on canvas, 40 x 56 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Some Days the Sky Is Just a Ceiling is a painting of the security door McKenzie used when she was going to work at one of the prisons. This work reminds us that while we may think about incarceration abstractly, its institutional logic is implemented in everyday life's specificity. Doors, bars, cells, security check procedures, access protocols—these devices and rituals are ideated and performed by humans to control other humans (people like you and me).

Sarah McKenzie, Corridor (Closed Facility, San Diego Youth Campus), 2022, oil and acrylic on canvas, 48 x 48 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

On a different note, Corridor echoes another type of institutional critique by showing us a transitional space used to move through the interior of a facility. The interesting fact here is that this corridor seems familiar. We have all walked in a similar space before. This painting points to one of the sub-themes of this show: the aesthetic and structural similarities between the prison space and other institutional spaces like schools, hospitals, churches, and museums.

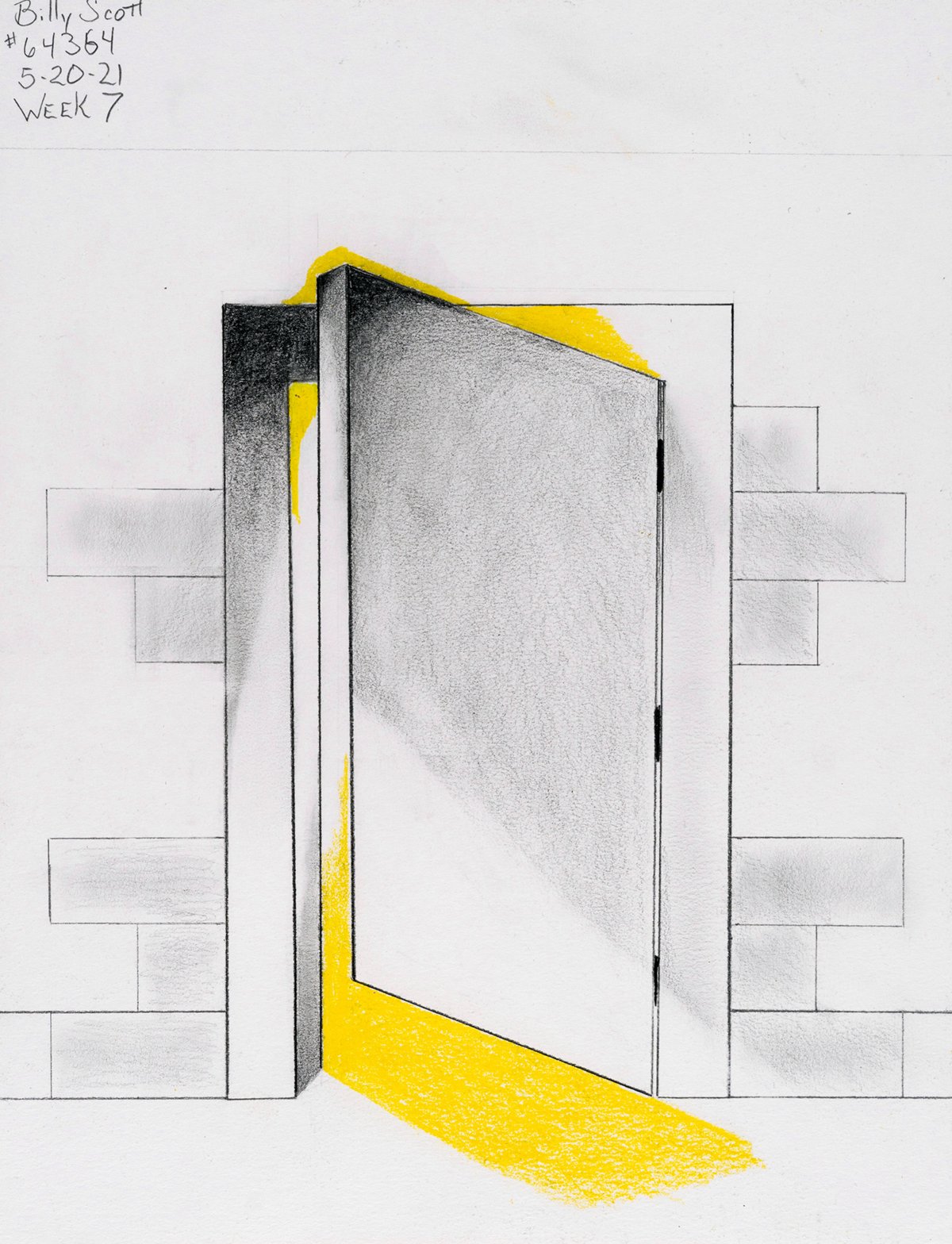

Billy Scott, Can I Come Into the Out Now? (Impossible Door), 2021, graphite and colored pencil on paper, 11 x 8.5 inches. Image by Nico Toutenhoofd.

In contrast, the works by the other artists in the show present a very freestyle, experiential, and sentimental approach that's sophisticated in its own way. Billy Scott's Can I Come Into the Out Now is a simple pencil line drawing depicting a half-open metal prison door. A bright yellow light emanates from the other side of the door, indicating the presence of a magical warmth outside behind the security door. Is the door opening or closing in front of us?

Shawna Hockaday, Locked Out, 2023, graphite and colored pencil on paper, 14 x 17 inches. Image by Nico Toutenhoofd.

Shawna Hockaday's Locked Out drawing shows a figure in a geometric cage that contrasts with an organic green landscape, making us think of the longing for nature and green spaces prisoners must feel while trapped in a concrete and metal incarceration complex.

Mario Rios, To Live With Death, 2022, acrylic on canvas board, 24 x 18 inches. Image by Nico Toutenhoofd.

Mario Rios, A Fish Tank For My Fish, 2023, acrylic on canvas board, 20 x 24 inches. Image by Nico Toutenhoofd.

Mario Rios's painting To Live With Death represents prison architecture in the shape of a skull and A Fish Tank For My Fish turns Rio's cell into an aquarium with Rios as a fish. The artist uses dark humor and poetic, playful analogies to reflect on the experiential aspects of incarceration.

Hector Castillo, Growing Up in My Cell, 2021, acrylic on canvas board, 16 x 20 inches. Image by Nico Toutenhoofd.

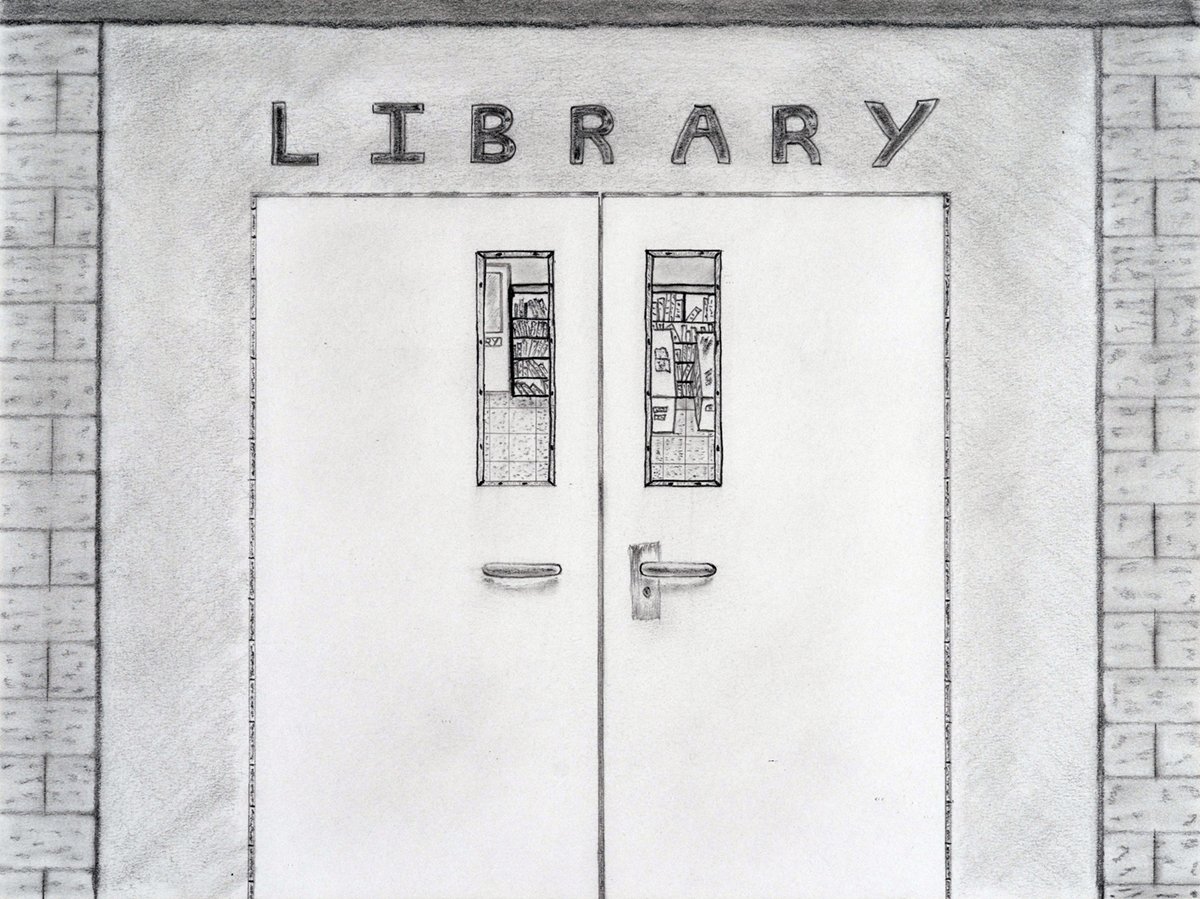

JR Gilbertson, The Learning Tree, 2022, graphite on paper, 9 x 12 inches. Image by Nico Toutenhoofd.

On a different note, Hector Castillo's Growing Up in My Cell depicts a peaceful quotidian scene typical of historic genre paintings. It shows Castillo in his cell, drawing, surrounded by his possessions (books, sneakers, coffee maker, and video games.). JR Gilbertson’s The Learning Tree focuses on the library door inside a facility. Both works bring brighter, warmer notes to the project by looking at moments of leisure, play, learning, or self-care, which we assume are also part of life in incarceration. They evoke ideas of resilience against adversity and hope for a better life and future.

A view of works in To See Inside: Art, Architecture, and Incarceration. Image by DARIA.

To See Inside: Art, Architecture, and Incarceration combines different dimensions of art practice. It brings together community activism and participation within the form of an art exhibition. It is an example of how art can have a direct, positive impact on someone's life conditions and the viewer's social awakening. At the same time, it brings into the public sphere agonistic perspectives that put accepted narratives into question, contributing to cultural enhancement and democratic debate.

An installation view of To See Inside: Art, Architecture, and Incarceration at the Museum of Art Fort Collins. Image by DARIA.

Sarah McKenzie and the rest of the folks responsible for To See Inside prove to us that art can be a progressive cultural device when it addresses issues of public culture with openness, thoughtfulness, responsibility, and care—reaching beyond trends and agendas. This project exemplifies how art can be a humble but key catalyzer of real democracy in times when it is very much needed.

Aitor Lajarin-Encina (he/him) is an artist, educator, and organizer born in Vitoria-Gasteiz, Basque Country, Spain, in 1977, the year of punk. He is currently living with his partner and children, working, playing soccer, and cooking paella in Fort Collins, Colorado. He received his BFA in painting from the University of Basque Country, Bilbao, and his MFA in visual arts from the University of California, San Diego. He is an assistant professor of painting in the Department of Art and Art History at Colorado State University, where he teaches painting, drawing, and socially-engaged art practice courses.

[1] Chantal Mouffe, The Democratic Paradox (London: Verso, 2009), 93.

[2] The artists included in the exhibition are Hector Castillo, Anthony Cole, Cayla Cushman, William Daniels, Ryan Flint, JR Gilbertson, Victor Gonzales, Luther Hampson, Lynell Hill, Shawna Hockaday, Matthew, LaBonte, Raul Luevano, Monique Lynch, Angelica Macias Williams, Sean Marshall, Joseph Taylor McGill, Justin Moore, Noir O’Dormin, Alejandro Ornelas, Mario Rios, Mike, Severson, Billy Scott, and Anonymous.