3óóxoneeʼnohoʼóoóyóóʼ /Ho’honáá’e Tsé’amoo’ėse: Art of the Rocky Mountain Homelands of the Hinono’eino’ and Tsétsėhéstȧhese Nations

3óóxoneeʼnohoʼóoóyóóʼ /Ho’honáá’e Tsé’amoo’ėse: Art of the Rocky Mountain Homelands of the Hinono’eino’ and Tsétsėhéstȧhese Nations

Gregory Allicar Museum of Art

1400 Remington Street, Fort Collins, CO 80524

August 29-December 15, 2024

Admission: Free

Review by Laura I. Miller

The story of “Friday” is one marked by betrayal and loss, as is the case for so many Indigenous peoples in the U.S.

A Northern Arapaho leader who lived near the Poudre River in Colorado in the nineteenth century, Friday was separated from his family and taken in by a white fur trapper who renamed him after the day of the week on which he was found. Friday learned English and became a translator. He served this role for the 1851 treaty that promised the Cheyenne and Arapaho people all of the land between the Arkansas and North Platte Rivers. Seven years later, when gold was discovered near Denver, the treaty was broken by the U.S. government, and most of the land was claimed by white settlers.

An installation view of 3óóxoneeʼnohoʼóoóyóóʼ /Ho’honáá’e Tsé’amoo’ėse: Art of the Rocky Mountain Homelands of the Hinono’eino’ and Tsétsėhéstȧhese Nations. Image by Laura I. Miller.

Reunited with his people, Friday and his band wandered his homelands as refugees for nearly a decade before finally being granted space on the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming.

Friday’s story is intertwined with Colorado State University’s history. As a land-grant university, CSU was endowed land in 1870 that resulted in the displacement of Indigenous Nations whose homelands were in the Rocky Mountains.

A view of the exhibition 3óóxoneeʼnohoʼóoóyóóʼ /Ho’honáá’e Tsé’amoo’ėse: Art of the Rocky Mountain Homelands of the Hinono’eino’ and Tsétsėhéstȧhese Nations. Image by Laura I. Miller.

The exhibition at CSU’s Gregory Allicar Museum of Art, 3óóxoneeʼnohoʼóoóyóóʼ /Ho’honáá’e Tsé’amoo’ėse: Art of the Rocky Mountain Homelands of the Hinono’eino’ and Tsétsėhéstȧhese Nations, shares Friday’s story, along with many other Indigenous artists, and asks the viewer to consider the question: “What can we do to return the resources of the land-grant university—knowledge, research, resources, and land—to Indigenous Nations?” [1]

Left: Heather Levi (Southern Cheyenne/Kiowa), Men’s Shirt, 2024, cloth; Middle: Gertrude Tallbull (Southern Cheyenne), Otsévóhto (pair of leggings), 1960, leather, quill, and human hair, from the collection of the Denver Art Museum; Right: Tsitsistas (Cheyenne) Artist (Great Plains), Hoestȯtse (dress), about 1890, beads on animal hide, from the collection of the Denver Art Museum. Image by Laura I. Miller.

“For this exhibition, I wanted to work with artists and art from Nations whose homelands were directly impacted by the land grant of Colorado State University,” said Emily Moore, associate professor of art history at CSU and co-curator of the exhibition, in an email. “These are many, but we decided to start with the Cheyenne and Arapaho because of their longstanding alliance and presence on the Front Range, and their shared treaty history following the 1851 Treaty of Horse Creek (AKA Treaty of Fort Laramie).”

“It was a much bigger project than anything I’d ever done at the museum before, and it really strives to teach more of us about Indigenous art of this land—past and present,” Moore said.

Colleen Friday (Northern Arapaho), Antelope Presence on Saint Lawrence Ridge, 2024, antelope hide, buckskin, glass seed beads, and brass spots. Image courtesy of the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art.

While the exhibition dedicates just one placard to Friday, which includes his portrait and a link to an audio recording recounting his story, his legacy carries on via the artwork of one of his descendants: contemporary artist Colleen Friday, who grew up on the Wind River Reservation. Inspired by the beadwork of her mother and aunts, as well as her own education and work in environmental conservation, Colleen Friday’s mixed-media pieces blend past, present, and future, illustrating the questions this exhibition asks us to consider.

George Curtis Levi, Colorado Before and After Sand Creek, 2014, mixed media on paper. Image by Laura I. Miller.

An installation view of White Bird (Cheyenne and Nez Pierce), Painting, 1894-5, pencil and paint on muslin, from the collection of the Denver Art Museum, gift of Mrs. John R. Livermore, 1958. Image by Laura I. Miller.

The exhibition places contemporary Indigenous artists’ works such as Colleen Friday’s alongside belongings from the late 1800s and early 1900s—a practice that feels especially poignant for Indigenous artists, whose culture we’ve attempted to erase. [2] For example, contemporary artist George Curtis Levi’s works, including Colorado Before and After Sand Creek, depicting illustrations on antique ledger paper, sits beside White Bird’s large-scale painting on muslin, a work commissioned by a U.S. army captain in 1894. Levi and White Bird employ similar styles, such as two-dimensional figures surrounded by ample white space, to reveal the biased histories about Indigenous peoples that were perpetuated by the white settlers and persist to this day.

Tsitsistas (Cheyenne) Artist (Great Plains), Xamaevee’e (tipi), early 1900s, canvas, wood, and beads. Image courtesy of the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art.

In addition to pairing Indigenous artists, past and present, the exhibition also displays many cultural belongings from Cheyenne and Arapaho Nations that were borrowed from the Denver Art Museum and the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. These include a beautifully embroidered xamavee’e (tipi), a he’ohko mestótse (pipe bag), a mámaa’e (war bonnet), and two hóánóhne (shields).

Tsitsistas (Cheyenne) Artist (Great Plains), Hóánóhne (Shield), before 1900, cloth, eagle feathers, rawhide, paint, and human hair, from the collection of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Image by Laura I. Miller.

While most of the works in this exhibition could be described as haunting, the implements of war are an especially powerful reminder of the unspeakable violence perpetrated against Indigenous Nations right here in Colorado, often as the result of unfair treaties that sought to extract them from their lands.

Tsitsistas (Cheyenne) Artist (Great Plains), Dog Soldier Sash/Rope, painted leather, feather, porcupine quills, and maidenhair fern sterns, from the collection of the Denver Art Museum. Image courtesy of the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art.

These cultural belongings of war are worn-in—threadbare and edged with dirt—having clear signs of being used repeatedly by the Cheyenne and Arapaho during battle. One such instrument, a Dog Soldier sash/rope by a Cheyenne artist, was used by the bravest warriors to stake themselves to the ground with an accompanying lance, “pledging to fight to the death unless a fellow Dog Soldier released them.” [3]

Left: Tsitsistas (Cheyenne) Artist (Great Plains), He’ohko (pipe), late 19th century, wood and pipestone, from the collection of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science; Right: Tsitsistas (Cheyenne) Artist (Great Plains), He’ohko mestȯtse (pipe bag), late 19th century, deer hide, beads, quills, horsehair, and tinklers, from the collection of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Image by Laura I. Miller.

The stories of Dog Soldiers, of Friday, of unfair treaties and atrocities won’t be found in most history books. And while some may say we need more legislation and more action to correct these injustices, which is true, this exhibition is a step along that path. It puts a spotlight on stories that have been swept away and humanizes history. For the artists and curators involved, as well as viewers who engage with the works, it reminds us of the rightful stewards of the land on which we stand and moves our hearts and minds toward restitution.

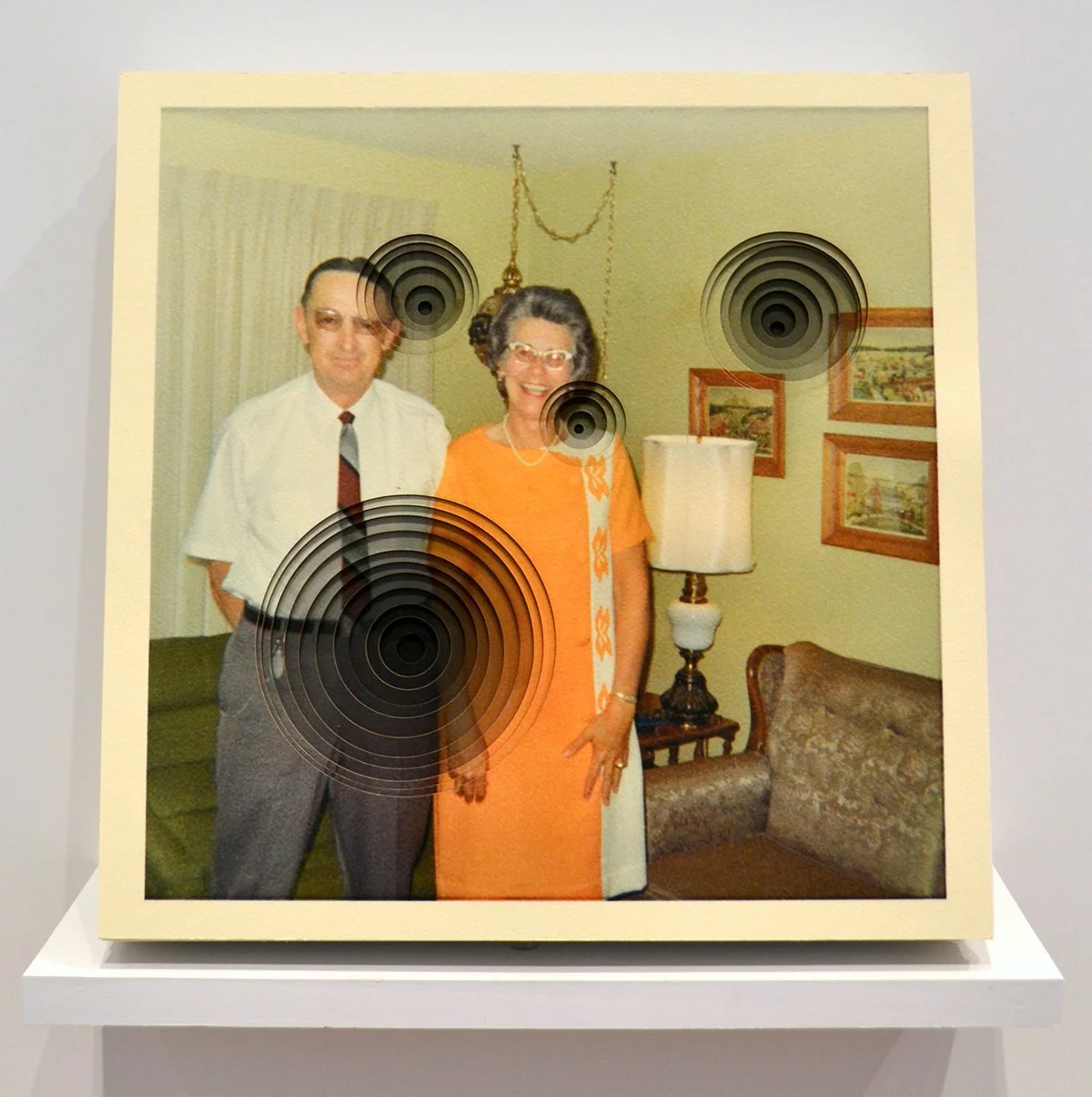

A display of works in 3óóxoneeʼnohoʼóoóyóóʼ /Ho’honáá’e Tsé’amoo’ėse: Art of the Rocky Mountain Homelands of the Hinono’eino’ and Tsétsėhéstȧhese Nations. Image courtesy of the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art.

“I think all of us were kind of shocked to study the impacts of the land grant system on Indigenous Nations,” Moore said of her CSU students who helped curate this exhibition. “...[I]t’s really heartening to see the next generation of museum professionals—and the next generation of these humans in general—who have such high ethical standards and who actively want to do better by Indigenous communities than we have in the past.”

Laura I. Miller (she/her) is a Denver-based writer and editor. Her articles, reviews, and short stories appear widely. She received an MFA in creative writing from the University of Arizona.

[1] From a plaque displayed in the exhibition. The exhibition was curated by Bruce A. Cook III (Haida/Northern Arapaho descent) from the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, George Curtis Levi (Southern Cheyenne/Arapaho) of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, and Emily Moore, Associate Curator of North American Art at GAMA. Students enrolled in Moore’s Fall 2023 art history seminar also aided in exhibition development, with the guidance of the co-curators and Tribal Historic Preservation Offices of the Northern Arapaho Tribe, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe, and Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma.

[2] The contemporary Indigenous artists included in this exhibition are: Max Bear (Southern Cheyenne), Bruce A. Cook III (Haida/Northern Arapaho descent), Aloysius Hubbard (Northern Arapaho/Navajo), Colleen Friday (Northern Arapaho), George Curtis Levi (Southern Cheyenne/Arapaho, Lakota), Halcyon Grace Levi (Southern Cheyenne/Arapaho/Kiowa), Eugene Ridgley, Jr. (Northern Arapaho), and Heather Levi (Southern Cheyenne/Kiowa).

[3] From the placard describing the sash.