A Thousand Beautiful Lies

A Thousand Beautiful Lies

Center for Creativity

200 Mathews Street, Fort Collins, CO 80524

October 30-November 23, 2024

Admission: free

Review by Paloma Jimenez

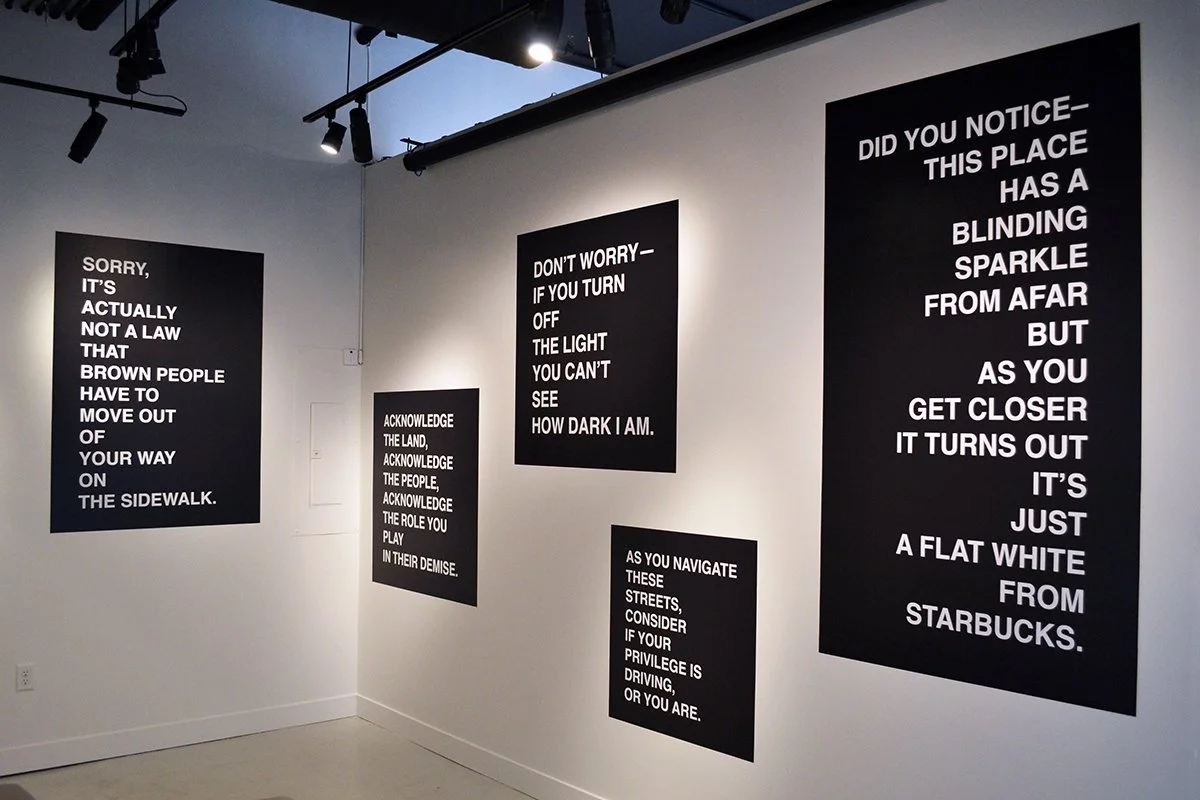

The United States government has proven time and again that it values economic power over human and environmental health. Each passing decade reveals more scorched earth, resources depleted for temporary gains, and tens of thousands of innocent civilians killed in war. Each week another hidden agenda comes to light too late. They enact these histories on a loop—new actors, same destructive decisions. A Thousand Beautiful Lies, organized by The Center for Fine Art Photography at the Center for Creativity, grapples with this reality in the context of the Atomic Age and the nuclear contamination that still continues to plague communities to this day.

The title wall and works in the exhibition A Thousand Beautiful Lies at the Center for Creativity. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

The Atomic Age is often portrayed by mainstream media as a concept of progress—a race to end a war, no matter the lives sacrificed. We know Oppenheimer, Truman, Stalin, and Franklin D. Roosevelt. The Center for Fine Art Photography exhibition switches the focus from political strategy to the lived reality of individuals and their surrounding contaminated environments.

An installation view of A Thousand Beautiful Lies. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Curated by Hamidah Glasgow, the artists Shayla Blatchford, Abbey Hepner, Bootsy Holler, Kei Ito, Patrick Nagatani, and Will Wilson use a variety of historically and emotionally charged materials to express the lasting, devastating impacts of nuclear warfare.

In the center of the exhibition A Thousand Beautiful Lies: Kei Ito, Where the Mountains Glow, 2023, uranium glass, inverted historical archive printed on metal, black light, light stand, and paper scroll. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Upon entering the gallery, a length of paper divides the space. Kei Ito’s decidedly obtrusive installation Where the Mountains Glow lists every known uranium mine on the land of the Navajo Nation. The top of the scroll rests against a platform presenting archival photographs held in place by uranium glass objects.

A detail view of the four 8 x 10 inch metal prints with uranium glass accompanied by a 30 x 310 inch scroll listing every known uranium mine on the Navajo Nation in Kei Ito’s Where the Mountains Glow, 2023. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

An arrowhead, a Native American head, a Peacemaker Revolver, and a butterfly glow with a secret radioactive warning. Ito explains that the work “shines a UV black light onto the invisible, forgotten, and ongoing trauma that still inhabits the land and the people.” [1] Conceptually tight and emotionally affecting in its dramatic scale, the work establishes the tone for the exhibition.

An installation view of works by Shayla Blatchford. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Shayla Blatchford’s intimate portraits of an Indigenous community affected by The Church Rock Uranium Spill of 1979 bring the issue of radioactive waste located within the Navajo Nation to a more intimate scale. Throughout the collection of photographs, pops of artificial colors disrupt the naturally lit surroundings.

Shayla Blatchford, Larry King was working at the uranium mill when United Nuclear Corporations tailings pond in Church Rock breached its dam. 94 million gallons of toxic waste leaked into the Puerco River which runs along his family's property line., archival digital inkjet pigment print, edition 1/1. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

The print titled Larry King was working at the uranium mill when United Nuclear Corporations tailings pond in Church Rock breached its dam. 94 million gallons of toxic waste leaked into the Puerco River which runs along his family’s property line. depicts a man sitting at his kitchen table with a guarded gaze. A hutch painted in a chartreuse hue eerily reminiscent of uranium ore frames his torso, hinting at the waste’s seepage into his daily health.

Will Wilson, Mexican Hat Triptych, photo-tex. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Will Wilson, Ship Rock, photo-tex. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Will Wilson’s photographs of abandoned uranium mines situated on the Navajo Nation’s territory also highlight the modern-day gravity of an environmental catastrophe that many might consider a problem of the past. Although Wilson employs the traditional techniques of landscape photography—misty horizon lines and golden stretches of sunlight—the naturally sublime is interrupted by the harsh geometry of nuclear waste mounds. In Ship Rock, a charcoal polyhedron rises out of the earth like a cursed tombstone. Foreboding dark clouds hover in the upper right corner of the photograph.

An installation view of Abbey Hepner’s Transuranic, 9 x 13 inch uranotype in locked box with 2 Geiger Counters and sound. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Unease permeates the air of the exhibition, as the proximity to radioactive material isn’t just symbolic. After a few moments in the gallery space, you’ll start to notice the unique erratic clicking of a Geiger counter. Abbey Hepner’s work in the exhibition features uranotypes, a photographic printing process that uses uranium, of “photographs captured at every nuclear site in the Western U.S. that transports radioactive waste to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in New Mexico.” [2]

Abbey Hepner, Rocky Flats Wildlife Refuge, Arvada, Colorado, Radioactive waste shipped to Waste Isolation Pilot Plant: 3.978.943 Gallons, uranotype. Image courtesy of the Center for Fine Art Photography.

The beguiling orange tones and soft textures of Rocky Flats Wildlife Refuge, Arvada, Colorado, Radioactive waste shipped to Waste Isolation Pilot Plant: 3,978,943 Gallons contrast with the reality behind the location’s nuclear history. Persistent clicks from the Geiger counter installation remind us that these spaces surround us on a daily basis, still testing positive for radiation, still impacting the health of surrounding communities.

Patrick Nagatani and Andrée Tracey, National Atomic Museum, Kirtland Air Force Base, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1989, Cibachrome print, edition 8/12, courtesy of the Colorado Photographic Arts Center Collection Loan. Image courtesy of the Center for Fine Art Photography.

Patrick Nagatani’s Cibachrome prints lean into a more cinematic style of imagery to bring awareness to the threat of the nuclear industry in the American Southwest. In the print National Atomic Museum, Kirtland Air Force Base, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1989, Japanese people leisurely enjoy sushi, unaware of the impending tragedy of the atomic bomb. The past is present, as nuclear weapons research still contributes to a large part of the New Mexican economy. The image flips pro-war United States propaganda on its head to reveal the true villain shrouded in red smoke.

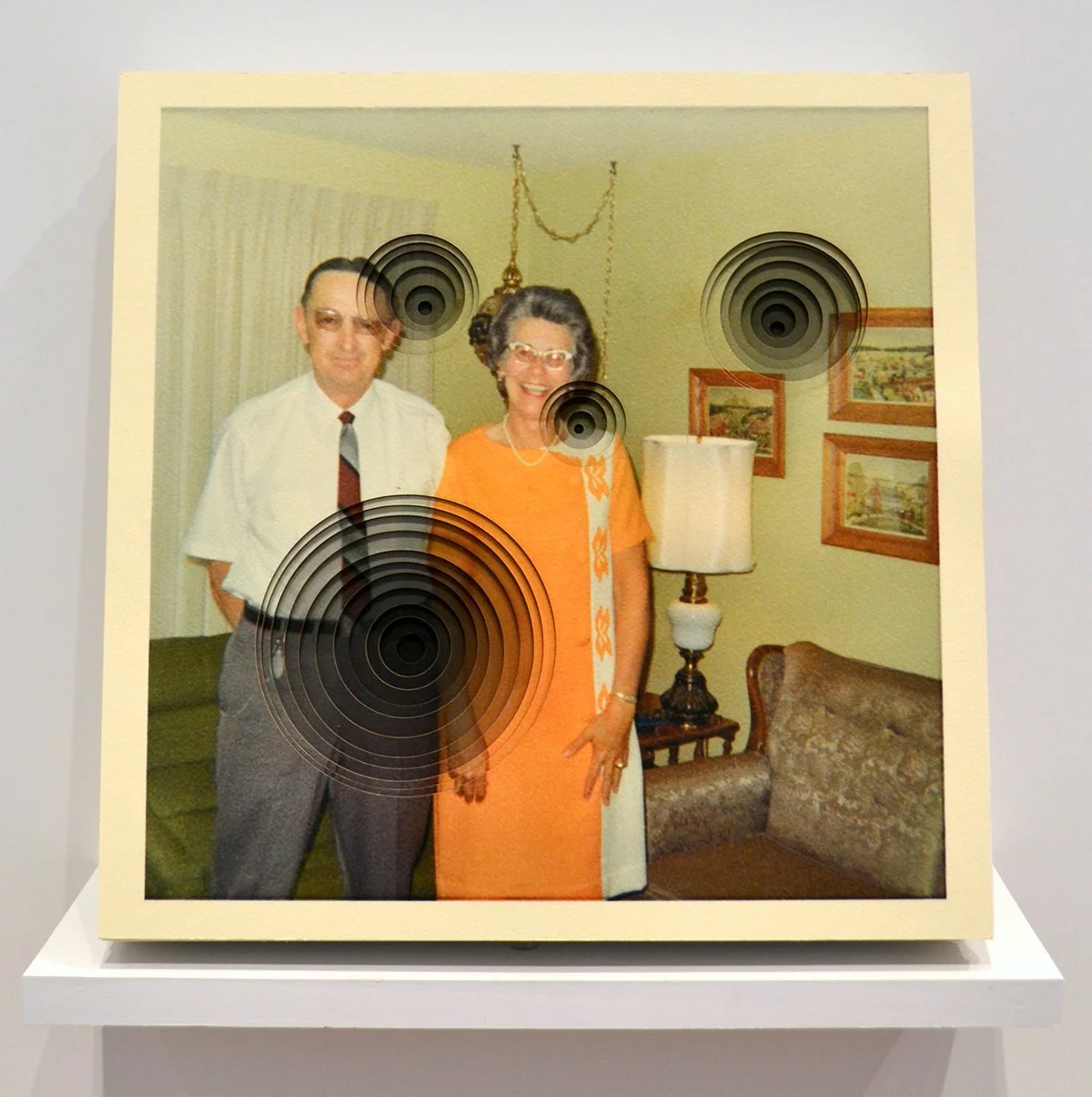

An installation view of works from the Contaminated series by Bootsy Holler. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Bootsy Holler also favors a targeted application of color in a collection of multimedia works from the Contaminated project, which focuses on the lasting impacts of the Hanford Nuclear site. Holler explains, “Contaminated is my experience growing up in this highly charged and secretive town and its impact on the community, people, environment, water, and land. Each unique piece is hand-built from family and friends' stories, pictures, and declassified documents.” [3]

Bootsy Holler, Dusty & Lou - Stomach Cancer, 2023, stacked pigment prints and matboard, unique 1 of 2 + 1AP. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Bootsy Holler, Jack - Classified, 2016-2021, stacked paper, pigment prints, rag paper, button, thread, and red ink stamp, unique 1 of 3 + 1AP. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Photos of smiling individuals from the town turn dystopian once you examine the violent placement of layered incisions into the paper. Dark circles of radiation illness overtake the image of a couple in Dusty & Lou - Stomach Cancer, 2023. The voids in the work threaten to swallow the memory whole. Even more disquieting is the piece Jack - Classified, 2016-2021. Tender-faced, looking off into the distance, the young man’s lips are sewn shut with a single button. His cause of death remains unknown to all but the government.

A view of A Thousand Beautiful Lies. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

From aerial perspectives of nuclear waste scarring the land to human lives cut short by cancer, A Thousand Beautiful Lies isn’t optimistic, and it doesn’t have to be. It’s haunting, informative, and offers space to hold complex feelings. We often turn to art to celebrate life, but also to mourn the loss of it. With this work, we are able to access information censored by the media, to understand the world from another person’s perspective, and to imagine something greater and more beautiful than the current reality.

Paloma Jimenez (she/her) is an artist, writer, and teacher. Her work has been exhibited throughout the United States and has been featured in international publications. She received her BA from Vassar College and her MFA from Parsons School of Design.

[1] Artist’s statement from an exhibition label.

[2] From the artist’s website, describing the Transuranic installation: https://abbey-hepner.com/#/work/transuranic/.

[3] Artist’s statement from an exhibition label.

![]MARGINS[](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5dade78ef3de04278ab5b4e8/1706556791874-RM7RABP1MHJ4GM9S100G/orimo_notes45+%281%29.jpg)