Resist: Tie Dye Practices Around the World

Resist: Tie Dye Practices Around the World

Avenir Museum of Design and Merchandising

216 E. Lake Street, Fort Collins, CO 80523

February 13–September 7, 2024

Curated by Paula Alaszkiewicz, Megan Osborne, and Brooklyn Benjamin

Admission: Free

Review by Laura I. Miller

Tie dye probably isn’t the first thing that comes to mind when you think of fine art. At least, it wasn’t for me. The exhibition Resist: Tie Dye Practices Around the World at Colorado State University’s Avenir Museum of Design and Merchandising might change your mind. [1]

An installation view of the exhibition Resist: Tie Dye Practices Around the World at the Avenir Museum. Image by DARIA.

Resist centers the artistry of shaped resist dyeing—a technique in which the cloth is manipulated through folding, tying, twisting, and binding—where textiles become canvases for artisans to imprint their movements and memories. The garments on display represent cultures across space and time, from India to Guatemala, starting in the late nineteenth century to present day.

Bandhani textiles from India in the exhibition Resist: Tie Dye Practices Around the World at the Avenir Museum. Image by DARIA.

The magic of the exhibition lies in its ability to evoke reverence for the art of cloth making, especially at a time when machine printing and fast fashion threaten to erase the craft, all while polluting the environment and placing significant strain on our natural resources. [2]

Àdìrẹ cloth created by the Yoruba Peoples using a stitch resist technique or by tying seeds or pebbles into the fabric. Image by DARIA.

Most Americans likely associate tie dye with hippie, youth, and counter-cultural movements of the 1960s and 1970s. However, this technique had been practiced for thousands of years around the world, with evidence of tie-dyed garments dating back as far as 4,000 BCE. [3]

A detail view of Àdìrẹ Alábẹ́rẹ́ and Eléso cloth, 20th century, cotton, Nigeria. Image by DARIA.

Like Cinderella stories, it’s unknown whether the practice evolved independently or through trade networks, such as the Silk Roads connecting China to the Mediterranean. [4] Garments on display at Avenir spotlight eight regional practices from Euro-America, Guatemala, India, Indonesia, Japan, Peru, Uzbekistan, and the Yoruba peoples.

Abr textiles from Uzbekistan in the exhibition Resist: Tie Dye Practices Around the World at the Avenir Museum. Image by DARIA.

A detail view of Abr Yardage, 20th century, silk, Uzbekistan. Image by DARIA.

Some of the most captivating garments on display are wedding clothes, such as the silk and velvet robes from Uzbekistan created using a technique called abr. Velvet abr requires significantly more yarn and highly skilled artisans to produce, making it expensive and rare. These robes were included in wedding dowries, and when the fabric wore out, it was repaired or repurposed instead of thrown away.

Ikat Hinngi, 20th century, cotton sumba, Indonesia. Image by DARIA.

Many of these expensive garments, whether hip cloths from Indonesia or kimonos from Japan, incorporate symbolism taking the form of plants and animals such as peacocks, trees, and roosters. For example, the Ikat Hinngi textiles from Indonesia are populated with designs depicting animals, including snakes. The Sumbanese peoples (from the island of Sumba in eastern Indonesia) believe that “motifs woven into cloth can impart special powers upon the wearer.” [5] In this culture, snakes symbolize rulers and their immortality.

Men’s Kimono, 20th century, silk, Japan. Image by DARIA.

A men’s silk kimono from twentieth century Japan takes the symbolism one step further, incorporating Japanese characters that, according to Chisato Nii Steele, instructor of Japanese at Colorado State University, can be arranged to read “Even if my name is no longer remembered.” [6] These words, combined with the depiction of a pine tree representing eternal youth, suggest the artisan’s intent with the kimono to have a piece of himself live on forever through his creation.

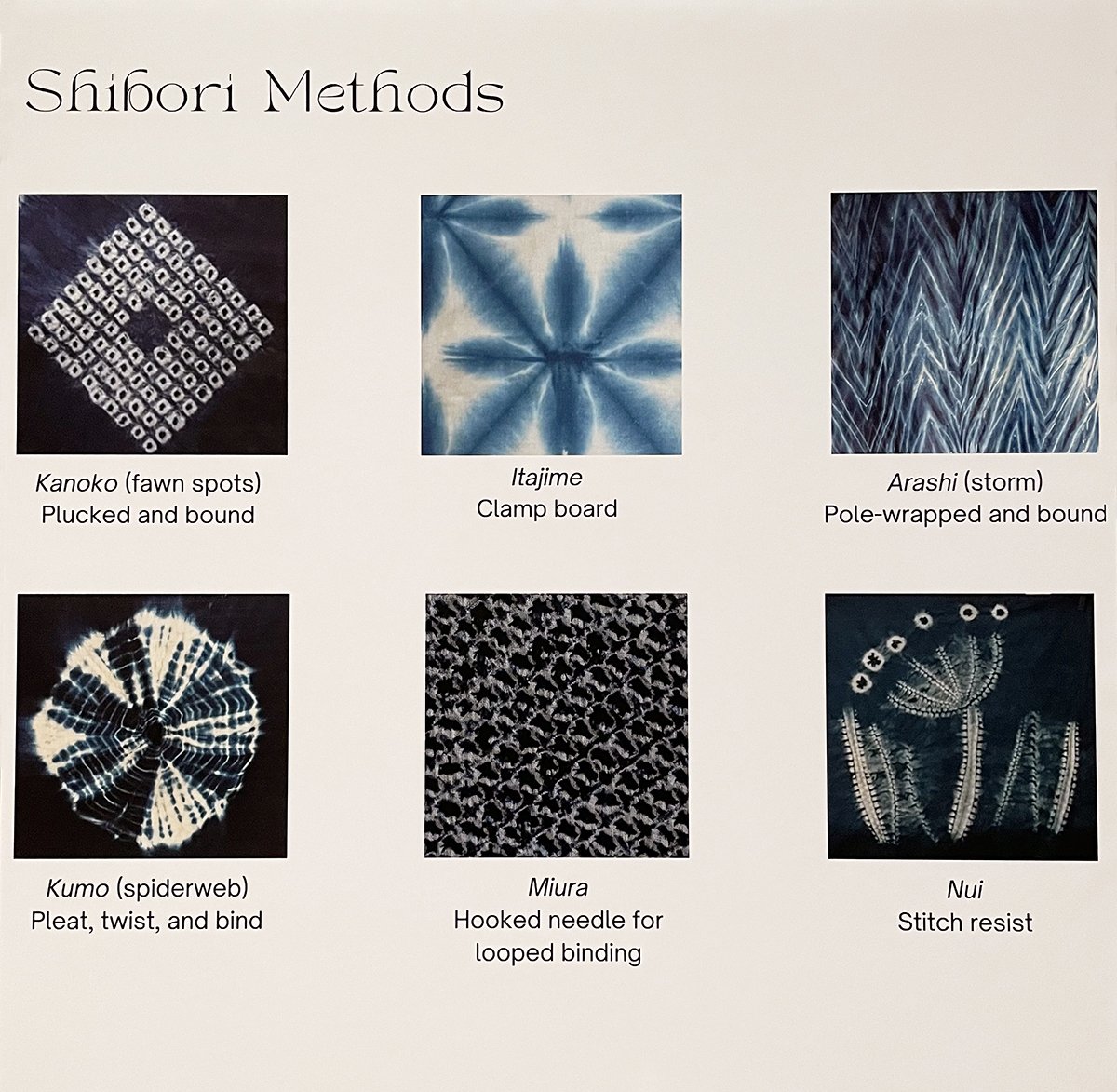

A diagram of shibori methods in the exhibition Resist: Tie Dye Practices Around the World at the Avenir Museum. Image by DARIA.

If you come away from the exhibition with nothing else, you’ll at least have a better understanding of the diversity of techniques used to create the garments’ intricate patterns. Resist’s curators do a great job of educating the viewer on the methods behind the geometry.

Bandhani textile length, 20th century, cotton, India. Image by DARIA.

I was surprised to learn that in addition to folding, rolling, knotting, twisting, and looping the cloth, artisans also used everything from rods to wax to seeds and pebbles to create a variety of designs. This results in natural flaws that, in contrast to printed patterns, capture unique traces of the artisan’s hands.

Hoodie and Shorts by Nike, 2023, cotton, U.S.A. Image courtesy of the Avenir Museum.

Compared with the deep cultural and even spiritual significance of the textiles on display from across the globe, the mass-produced tie-dyed garments we have in American stores—some also on display—seem appropriative at best and soulless at worst, lacking meaning and intent.

Jaspe textiles from Guatemala in the exhibition Resist: Tie Dye Practices Around the World at the Avenir Museum. Image by DARIA.

Overall, the exhibition paints a portrait of resilience and tradition, where textile production becomes a vessel for preserving heritage and identity, with meaning imbued in every thread. It calls attention to the dangers of industrialization and the dire need for a return to artistry, quality, and intentionality in an industry that has become corrupted by the all-consuming desire for low-cost alternatives and instant gratification.

Laura I. Miller (she/her) is a Denver-based writer and editor. Her articles, reviews, and short stories appear widely. She received an MFA in creative writing from the University of Arizona.

[1] From www.chhs.colostate.edu/avenir/about-us/.

[2] For more information, see psci.princeton.edu/tips/2020/7/20/the-impact-of-fast-fashion-on-the-environment.

[3] From www.chhs.colostate.edu/avenir/spring-galleries-2024/resist-tie-dye-practices-from-around-the-world/.

[4] See www.npr.org/2015/03/13/392358854/a-girl-a-shoe-a-prince-the-endlessly-evolving-cinderella.

[5] From www.chhs.colostate.edu/avenir/spring-galleries-2024/resist-tie-dye-practices-from-around-the-world/.

[6] Ibid.