Washi Transformed

Washi Transformed: New Expressions in Japanese Paper

Longmont Museum

400 Quail Road, Longmont, CO 80501

January 29-May 15, 2022

Curated by Jared Thompson

Review by Maggie Sava

Featuring the work of nine contemporary Japanese artists—Hina Aoyama, Eriko Horiki, Kyoko Ibe, Yoshio Ikezaki, Kakuko Ishii, Yuko Kimura, Yuko Nishimura, Takaaki Tanaka, and Ayomi Yoshida—the exhibition Washi Transformed unifies the artists’ diverse practices through an exploration of their shared use of the ancient medium of washi (和紙), handmade Japanese paper. The result is a show both distinctly focused and wonderfully abundant in unique expressions created through the artists’ contemporary aesthetic interventions.

An installation view of the exhibition Washi Transformed: New Expressions in Japanese Paper at the Longmont Museum. Image courtesy of the Longmont Museum.

Washi Transformed, a traveling exhibit organized by Meher McArthur and toured by International Arts & Artists, Washington, D.C., starts with a deep dive into the history, production, and qualities of washi. The intent is both to educate visitors who may be unfamiliar with the medium and to highlight its important cultural and material significance. [1] With a history spanning more than 1,000 years, washi has become, as the exhibition text describes, “a revered craft of expression, honor, community and a spiritual connection to nature.” [2] In this first section of the show, rhythm underscores the craft of papermaking through an explanation of scooping—the technique of swinging a frame back and forth to leave an even surface of paper solution on a screen to form washi. [3]

Kyoko Ibe, Hanging Sail, 2000, reinforced kozo washi. Image courtesy of the Longmont Museum.

After learning about the creation of washi and the features and attributes of different varieties—including an opportunity to touch each type and become familiar with their surface qualities and textures—the show moves out of the first hallway and into the main area where Kyoko Ibe’s sculpture Hanging Sail (2000) greets the eye. Designed to mimic a ship’s sails, the airy quality of the 19 curving sheets of white washi paper makes it seem like they are floating in midair. The slight abstraction of form and the attention to line and shape give a modern geometric quality to the work, which is balanced by the organic waves of the paper. It’s cleverly set near Ayomi Yoshida’s all-blue installation Blessed Rain (2021) to underscore the marine theme of the work.

Ayomi Yoshida, Blessed Rain, 2021, installation with woodblock-printed ink on indigo-dyed washi paper. Image by Maggie Sava.

Blessed Rain creates a second visual pull, inviting visitors into its large semicircle of hanging indigo washi. Once inside, this installation becomes immersive and environmental, creating a new world within this blue pocket in the middle of the gallery. Using the traditional woodblock techniques of the Edo period to create patterns of rain on the floor-length sheets of paper, Yoshida bridges the past and present to draw attention to the changes in Japan’s relationship to rain due to climate change.

Here, the medium helps tell the story as washi is intrinsically tied to the land and speaks to the sense of harmony with nature that is important in Japanese culture. [4] In her artist’s statement, Yoshida describes how rain has transformed from a life-giving blessing to a cause of natural disaster and distress. Her work asks viewers to “think about what we need to do to ensure a better tomorrow, in which we can again all be lulled to sleep by the peaceful sounds of the falling rain.” [5]

Kakuko Ishii, Japanese Paper Strings Musubu W1, 2007, washi paper and pigment. Image by Maggie Sava.

Play with natural form and environmental imagery continues in Kakuo Ishii’s various series featured in the exhibition. Japanese Paper Strings Musubu W1 (2007), for example, populates the exhibition with lively works that look like fantastical plants sprouting from the shelfs and pedestals of the gallery. The exhibition design accentuates the whimsical nature of the sculptures and creates a visual rhythm both of repetition and movement along the gallery walls. Although appearing as organic, fibrous organisms, the sculptures also maintain a contemporary feel with their abstracted quality, signifying how modern sensibilities need not be set in opposition to a deep connection to nature.

As the show progresses, the balance of organic and aestheticized forms in the washi works unifies the variety within the art, which ranges from two-dimensional works to sculptures to the functional household pieces of Eriko Horiki. Horiki’s practice focuses on interior design and the incorporation of washi within architectural spaces. Her works included in Washi Transformed demonstrate how she utilizes the physical qualities of the material to play with light, most prominently in Group of Ishi (Stone) Light Object (2017).

Eriko Horiki, Group of Ishi (Stone) Light Object, 2017, washi paper, resin molds, and steel light fixtures. Image courtesy of the Longmont Museum.

The smooth bodies of the light sculptures mirror large rocks, recalling the use of rocks in Buddhist temple gardens which serve to provide calm. [6] Horiki’s work evokes the sense of a natural environment within a constructed space and expands the purpose of the pieces beyond simple decor. They become devices for pause and visual contemplation, creating a sense of peace alongside their functionality.

Yoshio Ikezaki, The Earth Breathes, 2003, washi paper, sumi ink, and gold pigment. Image by Maggie Sava.

The use of washi as a material for meditation connects several artists’ works in the exhibition. Yoshio Ikezaki, for example, incorporates his ki, or energy, as part of his art-making process. This spiritual element is underscored in The Earth Breathes sculptures (2003), in which he sculpts dyed sheets of washi into the form of books and inscribes them with text from the Mahayana Buddhist text the Heart Sutra.

As the label describes, these pieces are a contemplation of the Heart Sutra concept that “form itself is emptiness.” [7] The energy held within the bodies of the sculptures emphasizes the artist’s hands, even in their absence. Although the forms are distinctive, they are also dark and nearly monochromatic, creating a sense of void. The unresolvable tensions in these sculptures sit with the viewer, causing them to question what exactly the forms entail and what they obscure or leave behind.

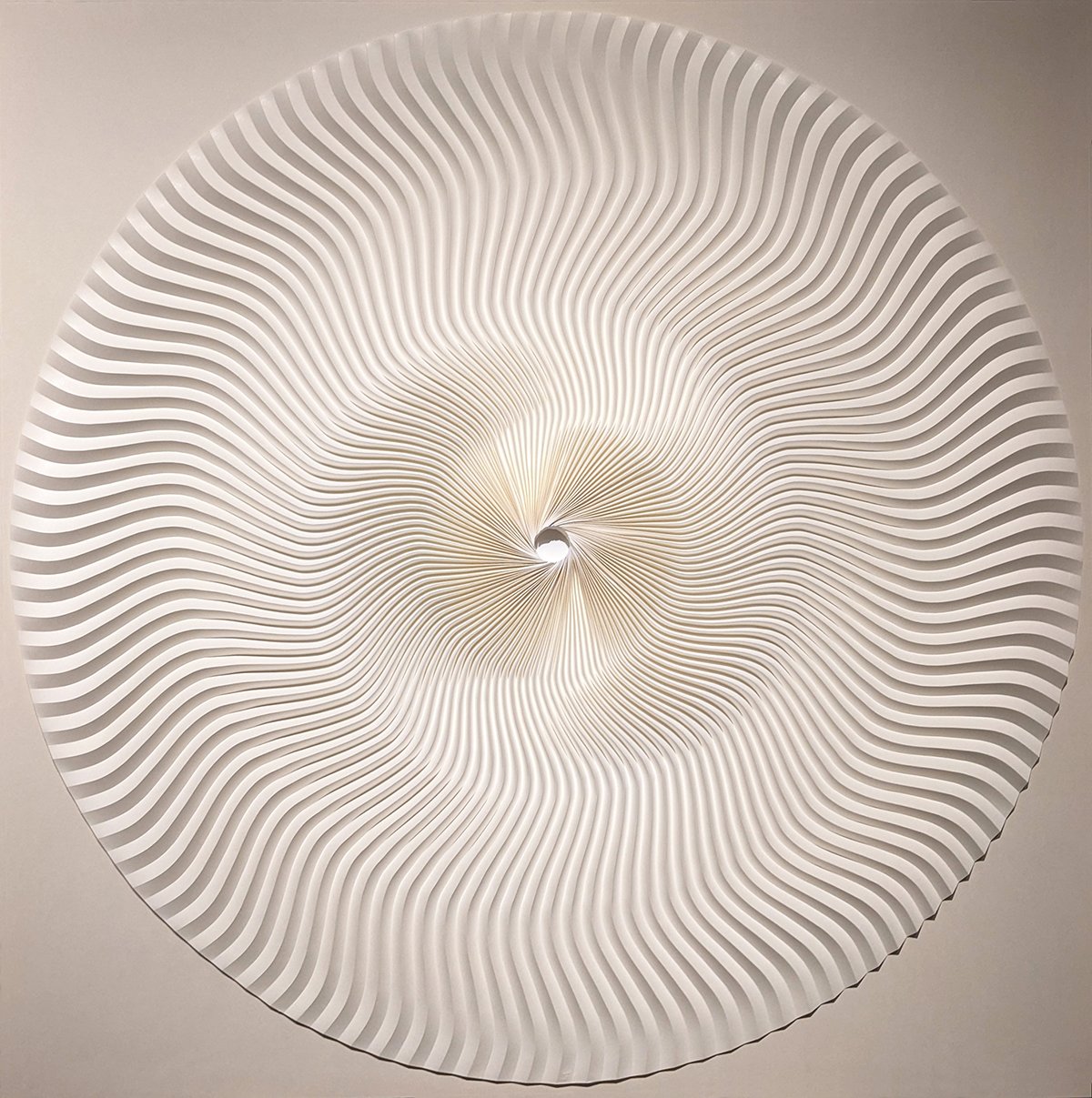

Yuko Nishumura, Line Transformation 03, 2021, kyokushi on wood panel wrapped with washi. Image by Maggie Sava.

In stark contrast to Ikezaki’s ash-colored sculptures and amorphous forms, Yuko Nishumura displays a bright white wall relief titled Line Transformation 03 (2021) made of kyokushi on wood panel and wrapped with washi. [8] However, the mesmerizing complexity of its creation and the undulating lines reveal a meditative construction and demand for visual rumination which connect it to Ikezaki’s work. This geometric study at first appears distinctly contemporary in design, bearing a resemblance to British artist Bridget Riley’s 1964 piece Blaze. [9]

With further consideration, though, it also looks timeless and cosmic, like the gills of a mushroom cap or the fossil of some primordial aquatic creature. The repeated motions of paper folding Nishumura uses to create her work, especially on a scale this large, indicates an almost ritual-like practice suggesting deep meditation through the artistic process. In turn, the movement created through repeated lines and varying dimensions produces an optical illusion that inspires the eye to play along the relief, questioning what we are really seeing in this work.

A detail view of Hina Aoyama, God-Ma, 2016, black origami paper on glass. Image by Maggie Sava.

Perhaps the most impressively precise and concentration-intensive works in the show are those of Hina Aoyama’s. These are made by cutting miniscule details into origami paper. As her artist statement attests, meditation is central to her art practice, evidenced by the unbelievable exactness of her art. In God-Ma (2016), she depicts mirrored horses facing a central form resembling a heart. The negative space and lace-like, delicate linework created through the cut paper demonstrates the artist’s technical mastery.

Because she adheres the paper to glass rather than to a backing, Aoyama also uses shadow as a part of her composition, repeating shapes and lines through the absence of light. The intention of this work is to encourage a man who was unable to walk through the representation of the horses as gods of transportation. This suggests a spiritual and mystical nature released through engagement with the design. [10] However, Aoyama is not always so forthcoming with the purpose of her art and prefers instead for viewers to determine their own interpretations by performing acts of introspection. [11]

The drama of Ibe’s Hanging Sail and Yoshida’s installation Blessed Rain that Washi Transformed opens with is mirrored by Takaaki Tanaka’s sculptures displayed on the other side of the exhibition space. Tanaka deconstructs washi to its fibers to build his intricate architectural and animal-like works.

Takaaki Tanaka, Boat Island, 2018, kozo (mulberry fiber paper), flax, and iron. Image by Maggie Sava.

Boat Island (2018) is a grouping of sculptures resembling insects floating across the gallery. They are cheerfully vibrant in color, donning bright green exoskeletons of iron mesh, washi paper, and flax fibers, interrupted by spiny yellow protrusions. The hexagonal mesh creates a beehive-like pattern in the body of the boats. Appearing as though they are mid migration, the boats stand out from the other softer colors of the show while also bridging the beginning and end as the school of boats meanders back towards the blue waters of Blessed Rain.

As a whole, Washi Transformed welcomes visitors in, inviting those who may already have a knowledge of the medium and those who do not. The show informs in a way that reflects the reverence of washi so that visitors can walk away within an enriched knowledge of the material and its myriad meanings and purposes. Although a traveling show, The Longmont Museum intends Washi Transformed to contribute to the museum’s overarching work of interconnecting local stories with larger international movements.

An installation view of Washi Transformed: New Expressions in Japanese Paper at the Longmont Museum with Eriko Horiki’s Group of Ishi (Stone) Light Object in the foreground. Image courtesy of the Longmont Museum.

For this particular show, the museum team is incorporating a series of programs to explore Japanese film, visual arts, and Japanese American experiences. [12] Through a discussion in their Voices of Change Series and a painting session at Longmont’s Kanemoto park, among other events, they also delve into the histories of Japanese Americans in Longmont specifically. [13] The result is several educational opportunities for visitors to expand on their experience with the exhibition and on their understanding of the stories, legacies, and traditions that shape their relationship to the show and its content.

Maggie Sava is a writer based in Denver, Colorado. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Art History and English, Creative Writing from the University of Denver and a master’s degree in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths, University of London. Writing is her main artistic engagement, which she pursues through research, art writing, and poetry.

[1] Coming from the Allentown Art Museum in Pennsylvania, Washi Transformed will be at the Longmont Museum until May 15th, 2022, after which it will be going to the D'Amour Museum of Fine Arts, part of the Springfield Museums in Springfield, MA. For a full schedule of the show, visit https://www.artsandartists.org/exhibitions/washi-transformed/#tour-schedule.

[2] Wall text, Washi Transformed: New Expressions in Japanese Paper, Longmont Museum, Longmont, CO.

[3] The label and wall text in the exhibition is available in English and Spanish.

[4] Wall text, Washi Transformed.

[5] Ayomi Yoshida, artist’s statement, Washi Transformed: New Expressions in Japanese Paper, Longmont Museum, Longmont, CO.

[6] Object label, Washi Transformed: New Expressions in Japanese Paper, Longmont Museum, Longmont, CO.

[7] Object label, Washi Transformed.

[8] Handmade paper. “Yuko Nishumura,” Esh Gallery, accessed February 1, 2022, https://www.eshgallery.com/en/artist/yuko-nishimura/.

[9] “Bridget Riley, Blaze, 1964,” Tate, accessed February 1, 2022, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/riley-blaze-p05083.

[10] Object label, Washi Transformed.

[11] Hina Ayoama, artist’s statement, Washi Transformed: New Expressions in Japanese Paper, Longmont Museum, Longmont, CO.

[12] One of the focuses of the programming, as director Kim Manajek states in the museum’s winter 2022 guide, is a reflection on the fact that 2022 is the 80th anniversary of the executive order authorizing the internment of Japanese Americans. In Granada, Colorado, Japanese Americans were incarcerated at the Amache camp from 1942 to 1945. Reflection on the local connections to this dark history and recognition of the injustices carried out within the state are critical in acknowledging the truth of what occurred and the lasting impacts it has had. Amache.org, accessed February 2, 2022, https://amache.org/.

[13] The Kanemoto family donated Kanemoto Park to the City of Longmont in 1966. A seven-acre park, it is located on the family’s former farmland, established by Goroku Kanemoto who immigrated from Japan in 1910. Within the park is the Tower of Compassion, built like a traditional Japanese temple. “Kanemoto Neighborhood Park,” Longmont Colorado City Facility Directory, accessed February 2, 2022, https://www.longmontcolorado.gov/Home/Components/FacilityDirectory/FacilityDirectory/36/710.