Uncommon Collective: Colorado Printmakers

Uncommon Collective: Colorado Printmakers

A.R. Mitchell Museum of Western Art

150 E. Main Street, Trinidad, CO, 81082

March 1-May 31, 2024

Curated by Jennifer Ghormley and Johanna Mueller

Admission: Free

Review by Gina Pugliese

On the second floor of the A.R. Mitchell Museum of Western Art in Trinidad, Colorado, a sign with Art Nouveau typography welcomes you to the Uncommon Collective: Colorado Printmakers exhibition. Art Nouveau artists, such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, created iconic, ornate posters that unified text and images in the early twentieth century.

A view of the Uncommon Collective: Colorado Printmakers exhibition and poster at the A.R. Mitchell Museum in Trinidad, Colorado. Image by Gina Pugliese.

They achieved this by employing printmaking methods such as intaglio (carving a design into copper or zinc plates to create a printable image, as in engraving or etching) and lithography (transferring images, drawn or painted on a stone or metal plate, onto paper). Thus, the Uncommon Collective poster suitably introduces visitors to an exhibit featuring eclectic printmaking methods still utilized by contemporary Western artists.

Amanda Palmer, Eugene on Love’s Razor Edge, linoleum block print, 21 x 27 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Local Trinidad artist Amanda Palmer’s Eugene on Love’s Razor Edge, the first artwork to the poster’s right, also greets you into the gallery. Dressed in a Victorian suit and holding a top hat in his paw, Palmer’s gentlemanly lion appears ready to serve as your host. Additionally, Palmer's use of negative space in this black-and-white print exemplifies a distinctive component of printmaking, highlighting the featured medium of the show.

Standing outside a saloon, Palmer’s lion evokes the Old West, a recurring theme in many of her pieces. Collectively, Palmer's fanciful prints about the lives of wild animals on the Western frontier comment on the museum as a space for Western art.

A view of the horseshoe-shaped mezzanine at the A.R. Mitchell Museum and the Uncommon Collective: Colorado Printmakers exhibition. Image by DARIA.

When I first entered the Museum, it was clear the building contained Western art from the allure of its old-fashioned architecture. Features such as its pressed-tin ceilings and “horseshoe-shaped mezzanine” struck me before my eyes focused on the art itself. [1]

A view of works by Arthur Roy Mitchell on display at the A.R. Mitchell Museum. Image by DARIA.

By “Western Art,” the museum means the cowboy art of Arthur Roy Mitchell, whose distinct, vibrant paintings and illustrations of people living in the plains of Southern Colorado and Northern New Mexico appeared on the covers of early twentieth-century pulp publications (inexpensive books and magazines). The museum holds a permanent collection of his work on the ground floor, leaving ample space for the Kuehl Fine Art Gallery and multiple temporary exhibitions in the rest of the building.

In contrast to Mitchell’s oeuvre, Palmer’s pieces refute the assumption that the Wild West is defined by and made for humans. Her lion challenges traditional narratives of the West, asking who or what is considered Western with questions such as: What characterizes the Western Victorian gentleman? Is it just his clothing and location, or is it also about the body inside the suit?

An installation view of the Uncommon Collective: Colorado Printmakers exhibition. Image by DARIA.

If the Western art in the museum began and ended with Mitchell’s caucasian cowboys and cowgirls, it would be complicit in whitewashing Western art history, allowing these icons to remain unchallenged as the heroes of this imaginary, monolithic West. However, with contemporary displays like the Uncommon Collective, the museum makes space to critique and expand notions of the West, its history, and the future of its artistic production. [2]

Amanda Palmer, Virgil’s Last Waltz, two block linoleum print, 21 x 27 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

In a similar spirit to the museum’s interest in a holistic view of the West, Uncommon Collective pushes viewers to ponder what, if anything, unifies contemporary printmaking in Colorado. Starting with rocky desert landscapes and allusions to Old West history, Palmer launches us into a bygone fantasy filled with well-dressed animals, including a bear in Virgil’s Last Waltz.

Amanda Palmer, I Met Coyote at the Archery Range, linoleum block print, 21 x 27 inches. Image by DARIA.

In other works such as Lily, Guadalupe, and the Jack of Hearts, rabbits munch tumbleweeds in people-less fields, and, in I Met Coyote at the Archery Range, a coyote in a loincloth nocks an arrow into its bow. Perhaps intermixing whimsy for whimsy’s sake, Palmer’s pieces also underscore the maelstrom of themes, contexts, and imagery at play in the exhibition.

Arna Miller, Sorry Cat, screen print, 11 x 17 inches. Image by DARIA.

Arna Miller’s playful screenprints of animals take on a similarly humorous tone. Using language to deliver punchlines, Miller’s marriage of image and text recalls the Art Nouveau poster introducing us to the gallery space. In Sorry Cat, a tabby cat in a cap with a messenger bag holds a cactus in one paw and lifts another, presenting a calling card that proclaims “SORRY”, and the text below continues “FOR PISSING ALL OVER AND RUINING YOUR STUFF”.

Arna Miller, The After Party, screen print, 18 x 24 inches. Image by DARIA.

Another print includes a black rat slurping a puddle of beer from a spilled can, surrounded by cigarette butts. In a different scene of indulgence, a squirrel bites into a donut, unperturbed by encroaching litter. In contrast to Palmer’s animals, depicted as politely imbibing at saloons, Miller’s party animals transport us to today's seedy underbelly, where animals live off the scraps of human hedonism.

Johanna Mueller, A Day Will Come, relief engraving, collage, and mixed media. Image courtesy of the artist.

Johanna Mueller celebrates Western fauna with more reverence than Palmer and Miller. In A Day Will Come, a wolf bust, haloed in stars and draped with a snake, looks proudly into the distance over a unicorn, its torso wrapped by another snake. A dense crowd of plants and other creatures frame this heraldic crest.

Johanna Mueller, Oil Field Ponies, relief engraving on topographic map. Image courtesy of the artist.

Downstairs in the Kuehl Fine Art Gallery, I found more of Mueller’s pieces, including a relief engraving on a topographic map, Oil Field Ponies, featuring the repeated image of a horse embellished with petroglyph-like markings on its hide. Although separate from the Uncommon Collective show, the echo of Mueller’s work in a different museum area underlined my assumption that the works in the space interact and refer back to one another. Moreover, contemporary artworks in the Kuehl Gallery develop the museum’s ever-expanding thesis on what distinguishes Western art. Beckoning us to look beyond the cowboy, Mueller’s Oil Field Ponies attends to the sacredness of the horse and the subtle and overt brutalities of the oil boom.

Theresa Haberkorn, Thalgau, linoleum block, woodcut, mixed media, and monoprint on vintage postcard. Image courtesy of the artist.

While Palmer, Miller, and Mueller’s works lack human protagonists, Theresa Haberkorn reminds us of the 19th-century men who explored and settled in expanding United States territories. Overlaid on a vintage postcard, her mixed-media monoprint Thalgau shows a man with an Edwardian mustache wearing a band-collar shirt standing in front of a red volcano surrounded by vines. The man alludes to settler colonialism's taxonomical and cartographical enterprises, which mapped newly claimed land and scientifically classified plants and wildlife.

Theresa Haberkorn, Hold it Together, linoleum block, woodcut, mixed media, and monoprint on vintage postcard. Image courtesy of the artist.

Haberkorn’s emphasis on flowers and butterflies in her other pieces highlights another recurring motif for Colorado artists: their interest in regional and international flora in addition to the animals of the West.

Three works by Victoria Eubanks in the Uncommon Collective exhibition. Image by DARIA.

Displayed adjacent to Haberkorn, Victoria Eubanks's works, showing the black silhouettes of birds, chairs, and human shadows against backgrounds of leaves in bold, flamboyant colors, pair nicely with Haberkorn’s smaller and more subdued prints.

Judy Gardner, Passage, monoprint with solar plate, linocut, stencils, and colored pencil, 22 x 30 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

On the other side of the room, Judy Gardner’s Passage offers a photographic image of a tree with different floral prints with a floriated mandala in the center. Inspired by Latin America, Gardner’s Peru takes us out of Colorado, weaving petroglyphs or cave paintings around an opium poppy, alluding to Peru’s ancient history and modern emergence into the illegal drug market.

Riannon Alpers, ABACA: Dimensional Broadside/Cryptothele Series (Lichen), 2023, over-beaten fermented abaca, dimensional frame, and monoprint. Image by DARIA.

With focused studies on moss and lichen, Rhiannon Alpers removes the human-centric markers of history, culture, and spirituality by concentrating on the shapes and intricacies of plants themselves.

Jean Gumpper, Unfurling Time, woodcut. Image courtesy of the artist.

Jean Gumpper also showcases decontextualized landscapes in woodcuts such as Unfurling Time, showing a zoomed-in perspective of a medley of leaves and branches.

Katherine McGuinness, Temple Wall, monotype, 40 x 39 inches. Image by DARIA.

Additionally, the petal- and leaf-like forms in Katherine McGuinness’s monotypes abstractly reference nature in a muted green, yellow, gray, and black palette punctuated with blocks of azure.

Tony Holmquist, Bowing Patterns, intaglio, 42 x 30 inches. Image by Gina Pugliese.

The prevalence of abstract artworks in the exhibition also spotlights the printmakers’ interests in non-representational expression. Tony Holmquist demonstrates this preoccupation in his large, 42-by-30-inch intaglio Bowing Patterns. The overlapping, bowed lines result in a composition that, at first glance, looks like a messy scribble even as he presents an orderly pattern.

Tony Holmquist, Currents, intaglio collage, 30 x 42 inches. Image by DARIA.

Another intaglio, Holmquist’s Currents, repeats these curved, thin black lines resembling a crude drawing of a bus among vertically running powerlines.

Mark Lunning, Confluence #2, polymer plate etchings with chine collé, 29 x 20 inches. Image by DARIA.

Mark Lunning’s polymer plate etchings echo the geometric shapes, interlocking planes, collages, and earth tones found in the cubist works of Albert Gleizes and Marcel Duchamp.

Joshua Butler, Elemental: Earth Meets Fire in a Field of Boundless Capacity, relief print and collagraph with encaustic, 24 x 36 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

On the other hand, Joshua Butler’s prints more closely align with abstract painting. Some of Butler's prints, including Elemental: Earth Meets Fire in a Field of Boundless Capacity, recall the transparent colors achieved through a painter’s light brush strokes, as in works by Agnes Martin, paired with the intentional splatter design made famous by Jackson Pollock.

Melanie Yazzie, Watching, monotype, 6 x 6 inches. Image by DARIA.

Another pair of artists in the show reflect on more intimate and emotional scenes. Melanie Yazzie’s monotypes collectively tell a story about a solitary house and a human figure under the watchful gaze of animals peeping around the structure. These works blend comfort with discomfort as Yazzie refrains from clearly establishing this vigilance as invited or invasive.

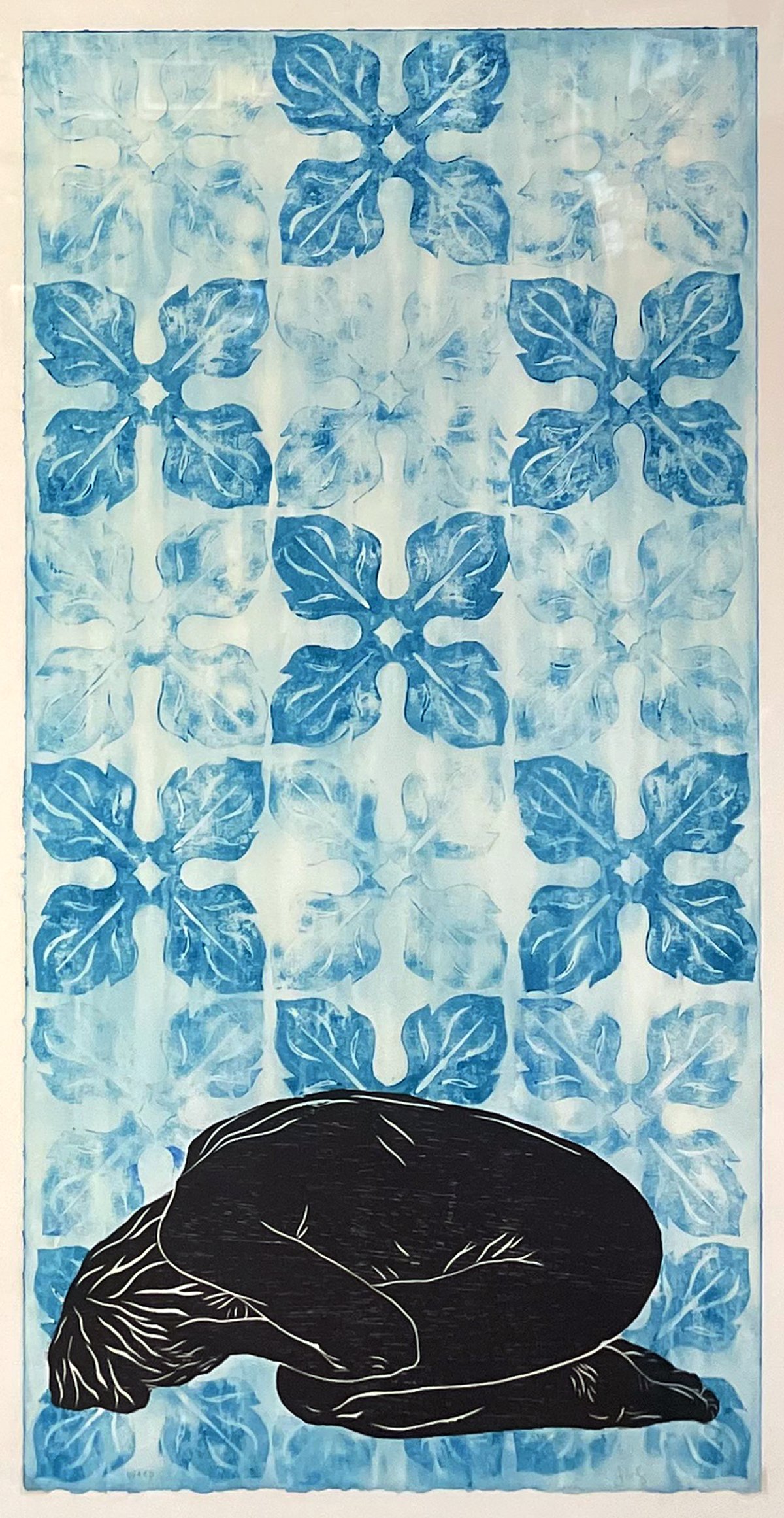

Jennifer Ghormley, Weep, shaped woodblock print and linoleum block print on Rives BFK paper, 18 x 36 inches. Image by DARIA.

Similarly, Jennifer Ghormley’s collapsed and weeping bodies against pastel backdrops evoke a mix of emotions as her uplifting colors and designs brutally contrast with the state of the figures.

A view of the Corn Mothers exhibition on display at the A.R. Mitchell Museum. Image by DARIA.

Even though I came for the printmaking show, I stayed for everything the A.R. Mitchell Museum had to offer. In a different exhibit, I learned about the Penitentes, a Catholic order of men in Spanish missions throughout the Southwest known for their self-flagellating rituals. Then, I delved into the Pueblo idea of the “corn mother” in another display featuring photographs of present-day women “who embody the spirit of the Southwest.” [3] These references to the region’s intermixed indigenous and Spanish colonial histories, impacting how we imagine the West today, demonstrate the museum’s sincere interest in providing a nuanced account of Western art that includes but does not privilege Mitchell.

A view of works by Arna Miller and Amanda Palmer in the Uncommon Collective: Colorado Printmakers exhibition. Image by DARIA.

The Uncommon Collective adds to these complexities surrounding notions of Western art while carving out a space for the medium of printmaking in the conversation. By the end of my self-guided tour, I determined that Colorado printmakers are, like most artists, united by their capacity to be inspired by manifold things, including but not limited to the Western landscape around them. Their interests in the abstract and more privately emotional aspects of life also place these artists under a larger umbrella of art, which spans the globe and centuries of art-making impulses and practices.

Gina Pugliese (she/her) was born in New Mexico but raised in Wyoming. After an academic tenure in New England, she cut hair in Denver for five years. Although transient and seeking equilibrium between Wyoming summers and New Mexico winters, she frequents Denver to write about its superlative art scene.

[1] On its website, the A.R. Mitchell Museum describes its own mezzanine using these words. See https://armitchellmuseum.com/.

[2] Part of this critique targets Mitchell, who inevitably references without outrightly crediting the vaqueros—skilled horsemen and cattle herders from Mexico whose attire, including wide-brim hats, chaps, and bandanas, emblematize the cowboy as we still recognize him today. The absence of people like the vaqueros in narratives about the West and its art ironically characterizes Western art itself. Even when Mexicans and Native Americans were portrayed in the early twentieth-century canon Mitchell participates in, their portraits were often drawn, painted, or sculpted by men of European descent who distorted their subjects through the lens of U.S. imperialism and Western expansion, whether they intended to do so or not. Learn more about the vaqueros from the Library of Congress’s “Buckaroos in Paradise: Ranching Culture in Northern Nevada, 1945 to 1982” collection and Jonathan Haeber’s 2003 article, “Vaqueros: The First Cowboys of the Open Range,” for National Geographic.