Albert Chong

Artist Profile: Albert Chong

The Sound of Trumpets and a Choir

By Gina Pugliese

Albert Chong is perhaps the most acclaimed photography, installation, and sculpture artist in Colorado who you’ve never heard of. His long and illustrious career includes pieces that he hopes, as his artist statement proclaims, “[give] expression to [his] human visual intuition, [operating] at levels inhospitable to verbal or literary expression.” [1]

Albert Chong, Chong with Cigar and Maka Shirt, 1997, digital pigment print, 26 x 20 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

After talking with him, I translated this statement to mean that his art critiques and questions what lies beyond a textual world that codifies bodies with social identities. As a social construction, markers of identity—such as race—are fictions. Yet such historically cemented, often-repeated fictions hold the authority to shape how we see ourselves and others.

Regarding the art world, the language of identity politics establishes a false expectation that all art by artists of color must address these politics while elucidating experiences of social marginalization. Refuting this reckoning, Chong strives to tap into loftier strata of aesthetics, taking us away from denigrated understandings of our existence founded on powerful social hierarchies expressed by and through language.

Albert Chong, Exhaling Ganja Smoke, from the I-Traits series, 1982, gelatin silver print, 39 x 39 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Chong claims his interest in photography began as a fluke. As a high school student in Kingston, Jamaica, he escaped the brutal heat following sports practice in the air-conditioned darkroom maintained by the Photography Club. As soon as he witnessed prints developing, he “heard trumpets and a choir.” Chong reflects, “If I could imagine an image and see it in my head, I could put it on film. I saw how quick it was—this possibility for image-making.”

After completing high school in 1977, he moved to Brooklyn, New York, where he involved himself in the Black Arts Movement—Amiri Baraka’s group of Black artists who, during the 1960s and 1970s, sutured activism and art under a banner of Black pride—as well as other organizations promoting art by people of color.

Albert Chong, Dancing with the Palo, from the I-traits series, 1983, gelatin silver print, 30 x 30 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Reflecting on being an emerging artist in the 1980s, Chong tells me, “Artmaking was seen as the domain of white males. Everyone else was being refused shows and access. We were the group that got our foot in the door.” Questioning who this “we” included, Chong humbly evades my curiosity, revealing only that he attended the School of Visual Arts around the same time as pop artist Keith Haring and the photographers Dawoud Bey and Lorna Simpson.

“Do you have any specific influences?” I probe from a different angle. “It’s impossible to be an artist and not be influenced,” Chong claims. “Artists are like sponges. We learn art similar to the way we learn language. Art has an accent to it.”

While hesitant to name names, Chong expands on an array of recent exhibitions focused on the artistic accent of ethnically diverse art practices at the end of the twentieth century. In October 2022, the Museum of Modern Art in New York exhibited Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, focusing on Linda Goode Bryant’s JAM Gallery (1974-1986) and the pieces exhibited there.

Albert Chong, Joe Beneath Termite Nest, from the Jamaican Portraits series, 1995, gelatin silver print, 56 x 44 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Chong recalls discovering the gallery while wandering through Manhattan. Two artists, David Hammons and Fred Wilson, were “manning the counters,” as Chong approached, inquiring, “How does someone get a show in this joint?” Later, after sending them slides, Chong received a show.

Sharing his portfolio with Black-run galleries like JAM proved more fruitful than sharing it with other galleries. “African American artists were prepared for rejection,” Chong tells me. “I was naive. I took my work to places where I loved their displayed work.”

Concerning one such experience, Chong relates:

“I loved this one photography gallery, and, so, I dropped off my portfolio. When I returned to pick it up, the people in the gallery gushed with enthusiasm. Well, you know how the story goes,” Chong chuckles. “I said that I was the artist, and their mouths dropped to the floor. They wished they could take back what they had said to me!

I had many experiences like that. When someone told me, ‘I’m sorry, we don’t show Black art,’ I would respond, ‘My art isn’t Black, it’s just art!’ Eventually, though, there were so many amazing artists of color that the system had to open up. Their talent couldn’t be denied any longer.”

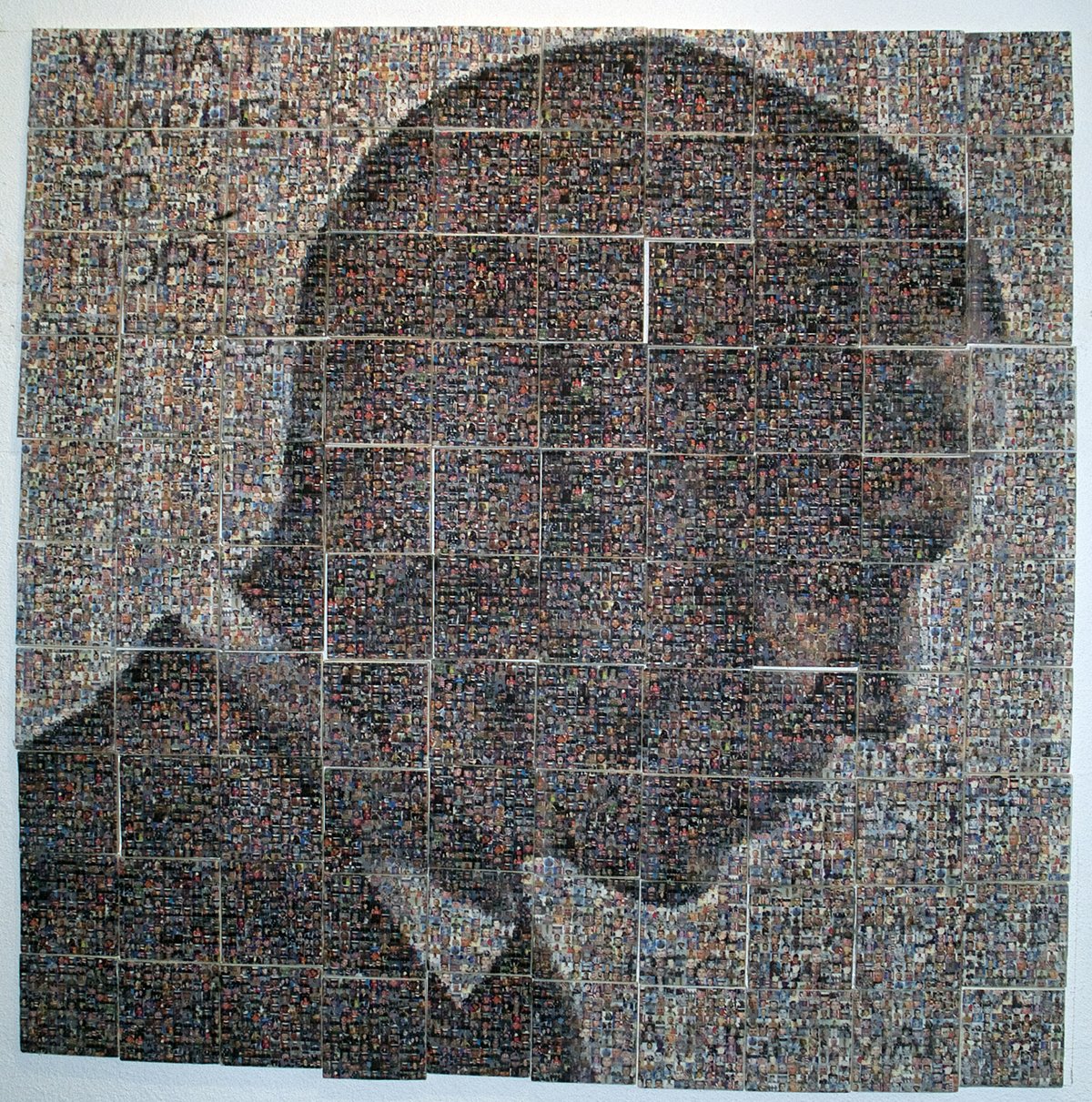

Albert Chong, Self Portrait as Victim of Colonial Mentality, from the Photomosaics series, 2010 (original image made in 1980), image transfer on 144, 4-inch tiles. Image courtesy of the artist.

In this moment of increased interest in Black and Asian diaspora artists, Chong counts himself “lucky because of his hybridity.” Yet, when I ask him about his ethnic background and its importance to his work, he suppresses a sigh, admitting, “I get that question a lot.”

His understandable fatigue reveals itself in the lengthy historical background he supplies: “I came of age knowing that I am this version of these two great cultures, African and Chinese, that ended up marooned on the small island of Jamaica. How these cultures come together is part of the story of the Caribbean.”

Albert Chong, Throne for the Justice, 1991, gelatin silver print, 30 x 40 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

For Chong, that story starts when the Chinese side of his family came to Jamaica in the 1840s, after the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. Following this liberation, formerly enslaved Africans refused to return to the sugar and cotton plantations as poorly paid laborers. England thus mined its colonies for the workers it needed to keep its empire profitable, including people from parts of southern China and India. These people were indentured to toil in Jamaican fields without a salary in order to repay their housing and overseas passage.

“My father who owned a shop like many Chinese people in Jamaica spoke Cantonese, but I never picked it up,” Chong imparts. “I was more immersed in Black culture, language, music, dance, and spirituality. I didn’t have the opportunity to engage the Chinese side of my family in the same way as the African-based side.”

Albert Chong, The Buddha, 1998, digital pigment print on canvas, 30 x 40 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Beyond celebrating the Chinese New Year and eating his father’s home-cooked Cantonese dishes, Chong’s identity, as he puts it, “was formed by the language and culture of the island of Jamaica.” Coming of age at the start of the country’s independent nation-building, Chong was exposed to a revival of the Marcus Garvey-inspired “Back to Africa Movement,” enthusiastically taken up by the Rastafarians. Swept up in the fervor of Black nationalism, Chong’s fellow Jamaicans joked that half of him would go back to Africa while the other half would go back to China.

“I am a hybrid of both cultures to some degree, but I am neither from Africa nor China,” Chong states. “If anything, I am just a hybrid, a mutt, a mongrel—hopefully embodying the best of both cultures.”

Albert Chong, Hope Deferred, from the Photomosaics series, 2011, mixed media and acrylic gelatin medium transfer on marble tiles, 60 x 60 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

The expectation that Chong’s work will reflect his mixed ancestry and Jamaican identity also feeds the assumption that politics imbue his aesthetics. Many of his pieces are indeed overtly political, particularly his Photomosaics series. In one mosaic, he collages a large portrait of Barack Obama from photos of soldiers killed during the U.S. invasions into Iraq and Afghanistan. The words “WHAT HAPPENS TO A HOPE DEFERRED” appear in the top left corner, referencing the Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes’ poem, “Harlem,” as well as the Obama presidential campaign’s “Hope” slogan.

“During Obama’s first term, I saw him as a moderate Republican in terms of his policies and his contributions to the misery in Iraq and Afghanistan started by George W. Bush,” Chong asserts, adding that, due to the social-political weight of this moment, he “couldn’t help but make these works.”

“Dwight D. Eisenhower coined the term ‘military-industrial complex’,” Chong says, expanding on the politics fueling his creativity. “He said we should be wary of it and how hungry it is for bodies and blood. Every dollar is red that isn’t going to the mouths of the people, and we are complicit in these murders with our tax-payer dollars. Considering these circumstances, the only power I have is to make art.”

Albert Chong, Abu Ghraib, from the Photomosaics series, 2010, acrylic gelatin medium transfer on stone tiles, 24 x 28 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Chong’s Photomosaics also include a collage of the grotesquely iconic photograph of Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh, who was tortured at Abu Ghraib, a portrait of Donald Trump, titled American Hitler (2017), and a portrait of Benjamin F. Stapleton overlaid with a letter penned by the Ku Klux Klan, drawing attention to the former Denver Mayor’s promotion of white supremacy.

Our conversation also veers to the recent death of Henry Kissinger, the former U. S. Secretary of State, who Chong deems “an angel of death” for his role in the destabilization and overthrow of foreign governments. Additionally, Kissinger’s policies amounted to egregious human rights violations and the deaths of thousands of people in Argentina, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Chile, East Timor, and more.

Albert Chong, Winged Evocations, 2000, in Havana, Cuba, installation. Image courtesy of the artist.

Kissinger was on my mind as I reflected on the 1960s and 70s presence of the CIA across the Caribbean islands, which Chong references in his installation piece, Winged Evocations (2000). When he showed this piece in the 2000 Havana Biennial, he used paper boats made from Phillip Agee’s book Inside the Company (1975), about the CIA, to hide Cuban artists’ responses to Chong’s questions concerning the Cuban state. He displayed their responses, hidden by the boats, in the center of a feathered Coptic cross.

Albert Chong, Feathered Crucifixes from the exhibition Winged Provocations in Havana, Cuba in 2000, feathers and paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

The U. S. also worked to destabilize Jamaican politics in the seventies, around the time the social democrat Michael Manley ran for Prime Minister. Like many Jamaicans, Chong considers Manley one of the country’s greatest leaders. Manley also became Chong’s friend and an admirer of his work. “I was glad when they put Manley and not Bob Marley on Jamaica’s one-thousand-dollar bill because then I could say I know someone on money,” Chong jests.

Albert Chong, Portrait of Carrie Mae Weems, 1994, gelatin silver print. Image courtesy of the artist.

Even though Chong knows the man on Jamaican currency, few people in Colorado seem familiar with Chong’s art. Indeed, while Chong has exhibited in New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Brooklyn Museum, he has yet to display his art in any major Colorado art museum. The only time his work appeared within the walls of the Denver Art Museum was at the entrance to the gallery for the show Modern Women/Modern Vision: Works from the Bank of America Collection (2022), for which they used his portrait of the artist Carrie Mae Weems in a collage of portraits of the artists featured in the exhibition.

In part, Chong thinks his invisibility in Colorado correlates with his lack of “schmoozing,” remarking that, because he doesn’t go to many art openings, “I set the paradigm to be ignored.”

Following the death of George Floyd and the rejuvenation of the Black Lives Matter movement, he admits that a few Colorado art museums featured him on their social media accounts, and a few curators contacted him, too. However, he confesses, “I want to be appreciated without it being contingent on being a part of an oppressed minority. I long for the day when artists of color don’t have to make ‘victim art’ or art about struggle or race.”

Albert Chong, Blessing the Throne, 1993, gelatin silver print. Image courtesy of the artist.

For these reasons, he prefers to inflect his work with “aesthetic beauty” over comments about xenophobic ideologies, attempting to make “work that transcends into a spiritual realm or is inspired by mysticism.” These preferred symbologies come out in Chong’s self-portraits in his I-traits series as well as in his Thrones series, in which he adorns a chair to signify Yoruba gods, his ancestors, or undisclosed entities. In such pieces, Chong uses idiosyncratic references to West African religions and Palo Monte—a Santería-like belief system. “It is not good to use these religions as artwork,” Chong admonishes, underlining his own oblique references to religion in his art.

Albert Chong, Some of the Bamboo Community, from the Jamaican Portraits series, 1994, digital pigment print, 20 x 26 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

We also discuss his often-overlooked Jamaican portraits, taken in the mid-nineties in Bamboo—a community on the northern coast of the island—with a large format, four by five view camera. He used type 55 negative/positive film, developing the negatives on the spot and giving the pictures to his subjects. “Ultimately these portraits look like documentary-type photographs because my subjects are rural Jamaicans with no embellishment,” he says. However, Chong also reveals that he wanted to present these people “in a dignified way.”

Albert Chong, Cindy, from the Jamaican Portraits series. 1995, digital pigment print, 30 x 40 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

“A lot of these people didn’t have images of themselves,” Chong explains, “And when I took their photographs, I told them, ‘I want you to think about how you want to be seen in the future.’”

A view of the construction of Chong’s rooftop gazebo at his “Carew Castle” in rural Jamaica, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

For his own future, Chong wants more time to work on his family’s remote Jamaican farm, acquired in 1968. Chong fondly recalls visiting the place as a child, getting out of hectic Kingston to raise pigs and tend crops that would later be sold in the city. After his father’s death in 1989, the family neglected the land until 2013, at which point Chong returned every summer to renovate and build on it.

Albert Chong, Chong in the Clouds, 1994, gelatin silver print. Image courtesy of the artist.

“It’s difficult for artists to retire,” Chong laments. “My continuing exhibition schedule prevents me from living in Jamaica full-time.” Hence, for the time being, Chong stays put in Colorado for most of the year, where he remains overlooked. Yet, hopefully, he finds some consolation in his assured position in the annals of art history.

Gina Pugliese (she/her) was born in New Mexico but raised in Wyoming. After an academic tenure in New England, she cut hair in Denver for five years. Although transient and seeking equilibrium between Wyoming summers and New Mexico winters, she frequents Denver to write about its superlative art scene.

[1] See https://www.albertchong.com/about.