The Everyday and Everyday Objects Recontextualized

The Everyday and Everyday Objects Recontextualized

FooLPRoof Contemporary Art Gallery

3240 Larimer Street, Denver, CO 80205

August 5-November 19, 2022

Admission: Free

Review by Madeleine Boyson

The Everyday and Everyday Objects Recontextualized at fooLPRoof Contemporary Art Gallery is a soft offering that will cushion the discordant shift from summer into fall. Led by gallery owner and artist Laura Phelps Rogers and true to its title, the large group exhibition edifies the commonplace through a medley of color, contour, and craft. Grounded in a loose thematic interpretation of “the everyday” over any single aesthetic, the fooLPRoof show leaves the “recontextualizing” to the viewer and rewards those who stop in to look.

A view of the entry area and title wall of The Everyday and Everyday Objects Recontextualized at fooLPRoof Contemporary Art Gallery. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Rogers is joined by fourteen other artists, all of whom approach the theme from a different quarter. Tracing the aim of The Everyday—which Rogers tells me is to “contemplate the mundane and elevate it to the point… [of] excite[ment]”—through each work is a potent incentive for curiosity and close looking. [1]

Tobias Flores’ installation of light switch covers in cast iron aluminum. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Tobias Flores’ light switch plates are a delightfully dark take on generic household items. Bob Ross figurine heads join a Millennium Falcon®, mandible bone, avocado, wrench, and the Pillsbury Doughboy® with an anvil as a few of the ornaments affixed to these cast iron aluminum covers. Flores displays a tri-tone Madonna on one plate, glorifying the other pop icons in the set as potential religious symbols. Casting the Christ figure and the Iron Giant together on another cover (both of whom sacrifice themselves for humanity in cultural lore), Flores lifts an earthly decorative detail to a metaphysical medium.

Laura Phelps Rogers, Wash and Dry, 2016, light-based mixed media work with digital photography. Image courtesy of FooLPRoof Contemporary Art Gallery.

Rogers also utilizes workaday motifs in her artwork and addresses the routines and crafts in women’s work. One sculpture is a simple, cast pair of folded jeans left un-patinated. Wash and Dry is similarly plain—a repurposed washer/dryer set opens to cloudy blue skies. This whimsical take on household labor suggests that the ordinary becomes magical when placed in the right hands.

Therese (Tess) Jones, Making Crazy series, 2012-2022, acrylic on canvas. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Therese (Tess) Jones equally engages with historically feminine topics in her artistic debut. [2] Her Making Crazy painting series of “crazy quilts” are modeled after a Victorian-era fad of elaborate “fancywork” quilting with industrialized textiles in asymmetrical, embellished patterns. From soup cans to hummingbirds, dog houses to evil eyes, Jones’ heavily decorated canvases adopt a folk art attitude to color, figure-ground relationships, and symbolism. In painting a traditional craft with a touch of surrealism, Jones reroutes the location of a centuries-old design from the home to gallery.

Leslie Aguillard, The Aftermath from the Noir series, 2014, oil on canvas. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

In aesthetic contrasts, Linda Lowry, Louis Recchia, Leslie Aguillard, and Laura Ahola-Young all display distinctive interpretations of the show’s theme. Lowry’s imposing, classical still life waffles between 2- and 3-D in the light from the gallery’s front window, with ponderous vases and ballerina bookends thrust into stark relief. Aguillard likewise uses size to her advantage to cast a noir scene with heavy emphasis on a generic corded telephone. Ahola-Young’s Algae (2021) is much smaller, but addresses the most ubiquitous (if overlooked) of all “everyday” objects: those photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms that produce between 50 and 80% of all atmospheric oxygen. [3]

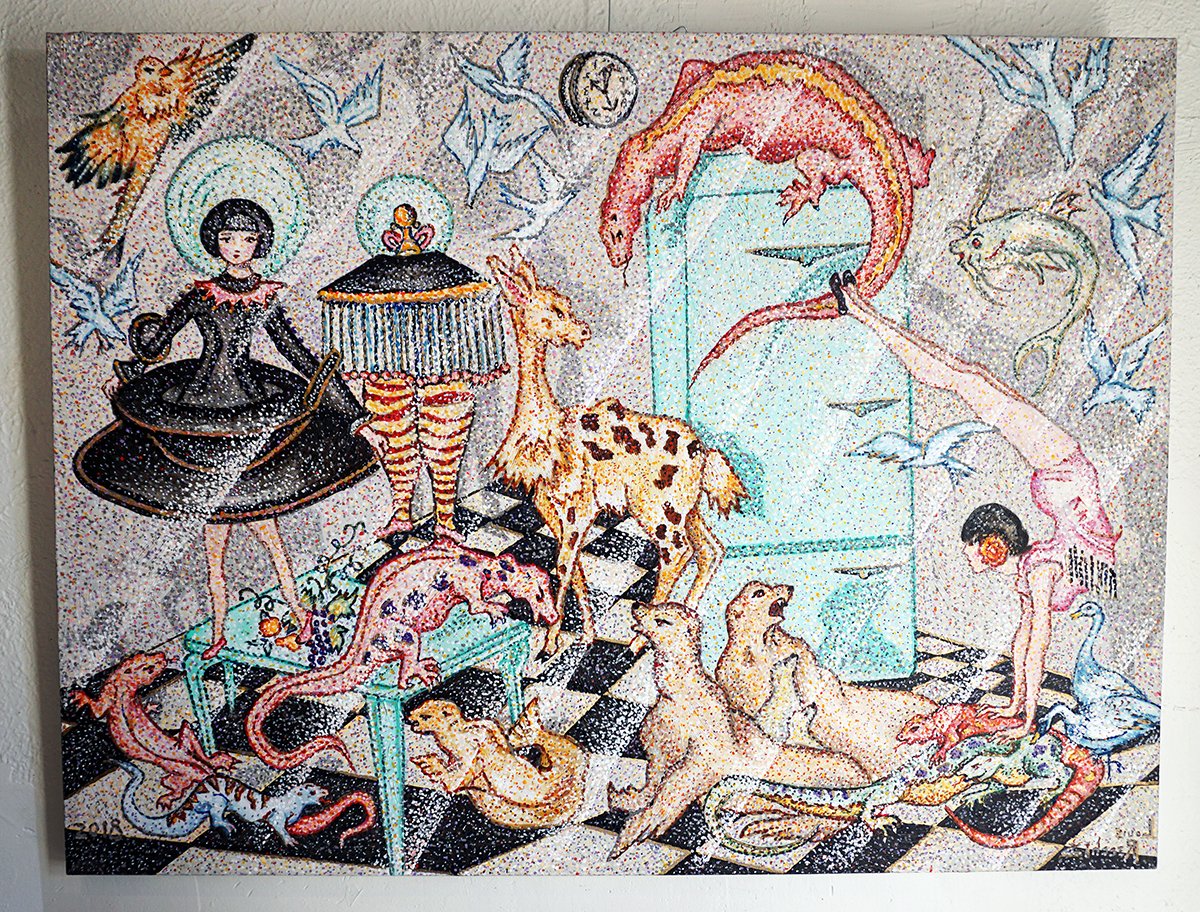

Louis Recchia, Dada Ballerinas, 2018, oil on canvas, 36 x 48 inches. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Like Jones, Louis Recchia also draws from art history. Among his several works in the show, Dada Ballerinas stands out for its surrealist and pointillist elevation of everyday items. A pool-colored refrigerator on a checkered tile floor is the backdrop for ballerinas, birds, lizards, seals, a giraffe-alpaca-hybrid, and a two-legged fringe lamp. Nearby, a hetero-chromic gray cat looms over a park scene in Luncheon on the Grass where the ordinary feels ever so slightly…odd.

From top to bottom: Sandy Lane, Our Room; The Tearoom; A Domesticated Room; Private Room; Your Room, all 2007, C-print photographs, 13 x 20 inches each. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Oddity is a defining factor in The Everyday, an intentional facet of the exhibition designed to elicit new feelings, according to Rogers. And nowhere is the odd more evident than in Nic Berumann and Sandy Lane’s surrealist photographs.

Berumann’s psychological works can be found in the back hallway where they are visible to and appreciated by patrons of a neighboring bar called Partners in Crime. Grisly scenes are perpetrated by vintage toys in sinister Christmas parties and on abandoned diner floors. Barbie® lays bloodied in a mousetrap; one doll is hanged by another; vivid racial stereotypes scorch the lens. Each macabre scene displays a masterfully-lit vignette using ordinary objects that speak to the artist’s experiences with bipolar, obsessive compulsive, and schizoaffective disorders. [4]

Sandy Lane, Sunroom, 2007, C-print photograph, 29 x 42 inches. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Less gruesome but no less detailed are Sandy Lane’s still lifes with fruit. These intimate photographs depict miniature domestic scenes set inside hollowed-out pumpkins, squashes, and watermelons. Tiny couches, beds, sinks, and chairs join the occasional bouquet or stray sheep behind rind doors or sewn and safety-pinned windows. Lane’s voyeuristic mise-en-scènes require a variety of materials and careful planning (fruit will decompose quickly)—a combination that is reminiscent of the popular late-1990s I Spy book series.

A view of Laura Phelps Rogers' The Art in the Everyday Community Quilt Project featuring over 800 submissions, ongoing, mixed media on wooden discs. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

But The Everyday is really built around Rogers’ The Art in the Everyday Community Quilt Project. [5] The massive, 37-foot-long “social engagement” installation in the front gallery is visible from the street and composed of nearly 900 wooden discs decorated in ephemera by over 860 artists. The Everyday is the quilt’s second appearance in Denver, where it hangs on white ribbons from the ceiling and waves in the breeze when visitors walk past.

A detail view of Laura Phelps Rogers' The Art in the Everyday Community Quilt Project featuring over 800 submissions, ongoing, mixed media on wooden discs. In the foreground, the discs include U.S. dollars and a design using cardboard. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

The “quilt” isn’t so much a blanket as it is the largest set of doorway beads known to humankind. Discs sport packaging materials, dollar bills, scribbles, ocean trash, magazine collages, masks, bra pad inserts, plastic foliage, postcards, crushed La Croix® cans, glasses (of all types), spilled paint bottles, nests, seashells, and a host of other curiosa that, in traditional gestalt fashion, amount to more than the sum of their parts. The resulting installation invites close looking on the part of the viewer who will never take in every disc but will nonetheless be rewarded for their curiosity.

A detail view of Laura Phelps Rogers' The Art in the Everyday Community Quilt Project featuring over 800 submissions, ongoing, mixed media on wooden discs. In the foreground, the discs include plastic debris, seed beads, an empty paint tube, and a paint brush. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

The beauty of this quilt, Rogers says, is that it is ultimately out of her hands. She’s asked participants to provide something from “the everyday,” but aesthetic, craft, materials, and palette are at the artists’ discretion. In fact, The Everyday and Everyday Objects Recontextualized as a whole is predicated on leaving interpretations to others.

By accommodating variations on “the everyday,” Rogers assembles an eclectic exhibition full of experimental works that may or may not have been accepted by more conventional galleries. “You can’t make decisions based on what will sell or not,” she says. Instead, Rogers and fooLPRoof re-contextualize the everyday art gallery, providing a welcoming space for artists and viewers to explore.

Madeleine Boyson (she/her) is an Editorial Coordinator at DARIA and a Denver-based writer, artist, lecturer, and curator who concentrates on American modernism, poetry, photography, and (dis)ability studies. She holds a B.A. in Art History and History from the University of Denver and volunteers as development director for the arts platform Femme Salée.

[1] This and subsequent quotes by Rogers are from the author’s visit to fooLPRoof gallery on September 3, 2022.

[2] Dr. Therese (Tess) Jones is currently the Associate Director of the Center for Bioethics and Humanities and Director of the Arts and Humanities in Healthcare Program at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

[3] From the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) website: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/ocean-oxygen.html.

[4] According to the artist’s website: https://nicholasberumann-manifestations.blogspot.com/.

[5] The Art in the Everyday Community Quilt Project was started by Rogers at an artist residency in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. The project then traveled to the University of Hawaii where it hung in an atrium and gathered more discs. The project slowly grew over COVID and continues to accumulate more discs to this day.