A Wink is Just a Wink

Amber Cobb: A Wink is Just a Wink

Galleri Gallery at Meow Wolf Denver

1338 1st Street, Denver, CO 80204

September 8-November 30, 2022

Admission: Adults: $45, Children ages 4-13, Seniors, and Military: $40

Review by Danielle Cunningham

The grid has an unwavering influence on contemporary art, often becoming the method of organization that underpins visual media and aiding viewers in their ability to absorb visual information. Occasionally, artists have disrupted the grid’s system of intersecting vertical lines and horizontal planes, acknowledging these boundaries only to question and discard them. In Amber Cobb’s new paintings and sculptures on display at Meow Wolf Denver’s Galleri Gallery, the artist uses the grid as a tool of order and chaos, a seemingly conflicted notion that introduces in systems like linguistics and spatial dynamics and encourages viewers to explore spaces beyond boundaries.

A view of Amber Cobb’s exhibition A Wink is Just a Wink in the Galleri Gallery at Meow Wolf Denver. Image by Wes Magyar.

The exhibition A Wink is Just a Wink is made up of six small paintings and two wall-mounted sculptures, all of which allude to the repetition of the grid with their echoing colors, shapes, and textures, creating a sense of harmony. Complicated in their composition, the works’ pastel color palette is a familiar nod to modern femininity, though their harsh and subtly imperfect angles and abrasive surface textures generate an expansive rather than specifically gendered subtext. Beyond that, these works are a combination of visual cues that make them seem simultaneously like relics from a distant history and harbingers of a future civilization—a notion Cobb establishes with her ability to straddle binaries.

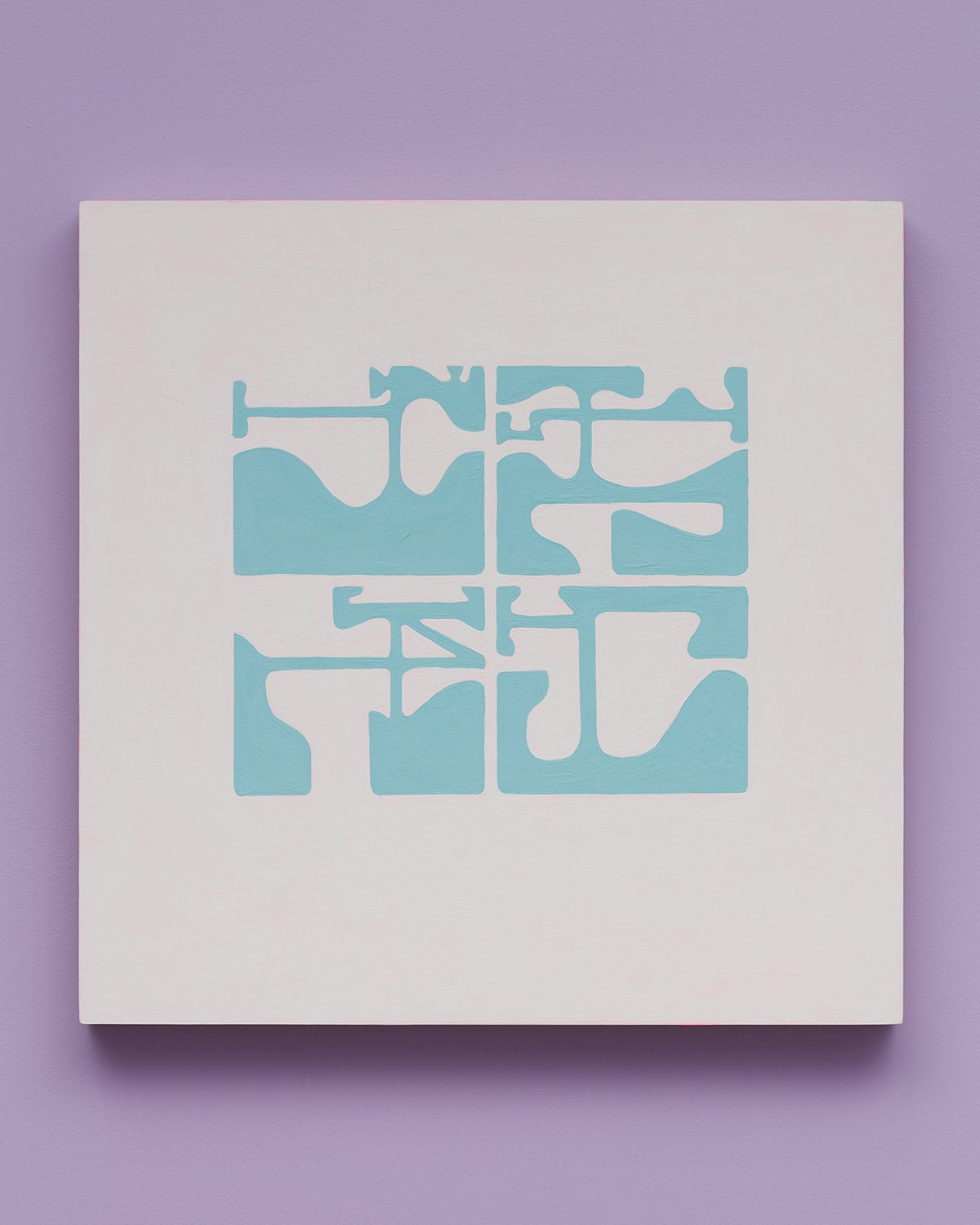

Amber Cobb, Connotative Layers, 2022, gouache on wood panel, 20 x 20 inches. Image by Wes Magyar.

Cobb’s paintings feature multiple rows of small, many-limbed characters that are evenly spaced and perfectly placed on invisible lines, calling to mind the textual serif characters of a forgotten or perhaps extraterrestrial language. Using the invisible grid like a handwriting ledger to contain and define each tightly spaced character, the artist holds their rough, rectangular bodies captive amid an atmosphere of white space. The white space functions as more than background though, as its bumpy and unrestrained surface mimics the surface seen in the foregrounded characters, generating spatial tension between artwork and viewer.

Four works by Amber Cobb, on the left wall: Pink Wink, 2022, gouache on wood panel, 20 x 20 inches, and Linger, 2022, gouache on wood panel, 20 x 20 inches; on the right wall: To a Certain Degree, 2022, wood, plaster, paper pulp, and enamel paint, 35 x 19 x 9 inches, and To a Certain Extent, 2022, wood, plaster, paper pulp, and enamel paint, 34 x 16 x 11 inches. Image by Wes Magyar

The thickly painted texture is visceral, demanding to be touched, and yet, that impossible desire is suppressed by the knowledge that these are elevated art objects, effectively untouchable. Also, the artist’s hand is noticeable as there are curves and other hand-painted marks, maintaining a subtle boundary between the characters and the background despite their congruous textures.

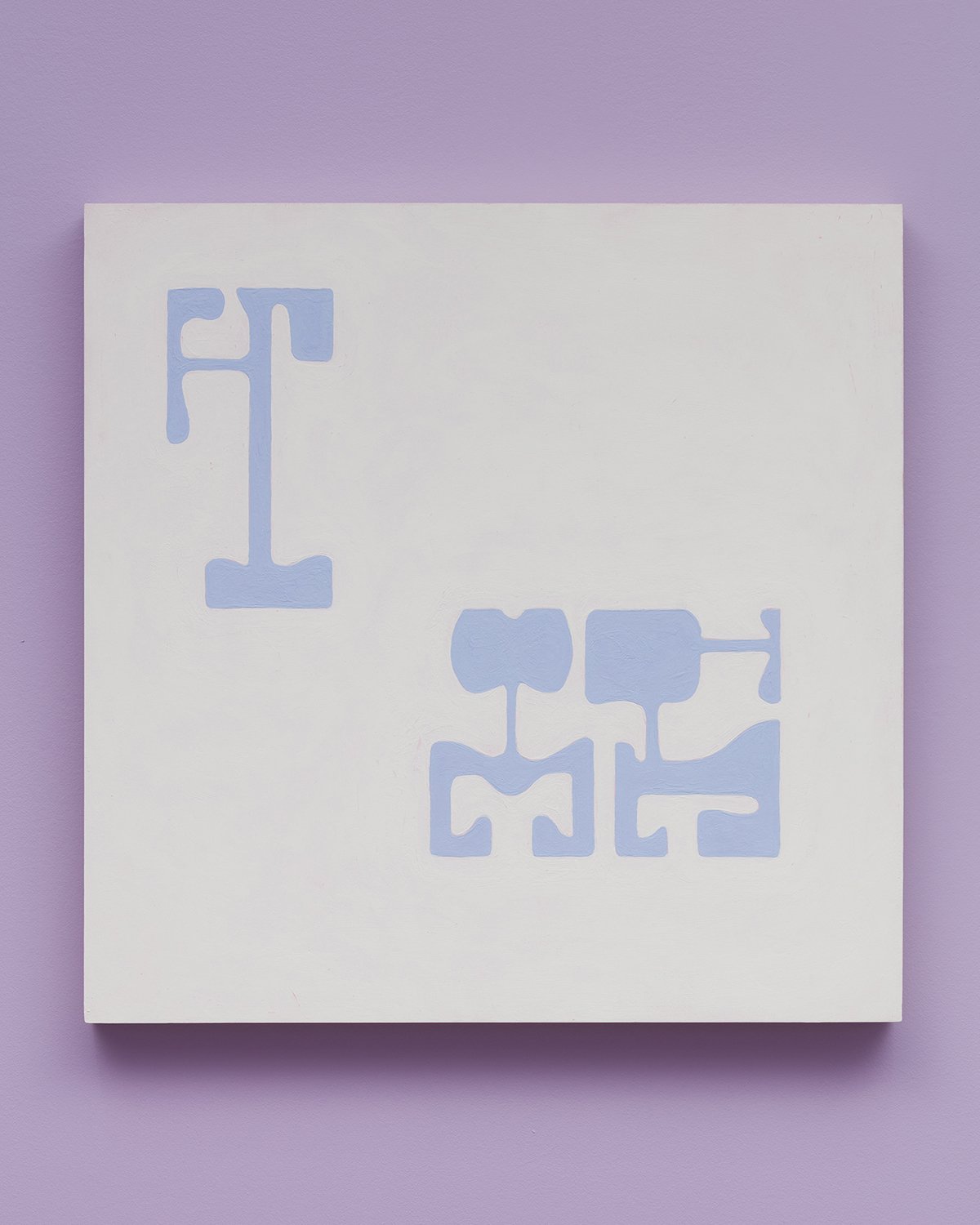

Amber Cobb, Trinity, 2022, gouache on wood panel, 20 x 20 inches. Image by Wes Magyar.

Though Cobb’s paintings are similar, each one differs in the number of characters, rows, and columns. Their message is as interchangeable as their aesthetic, except for the periwinkle-colored Trinity. As its title suggests, it features only three characters, a sparsity that sets it apart from the other busy, painted works. Unlike the other paintings, Trinity features a rare abundance of white space, relinquishing tension and emphasizing the meditative quality of the artist’s hand as she noticeably paints simple, tight brushstrokes that outline the characters.

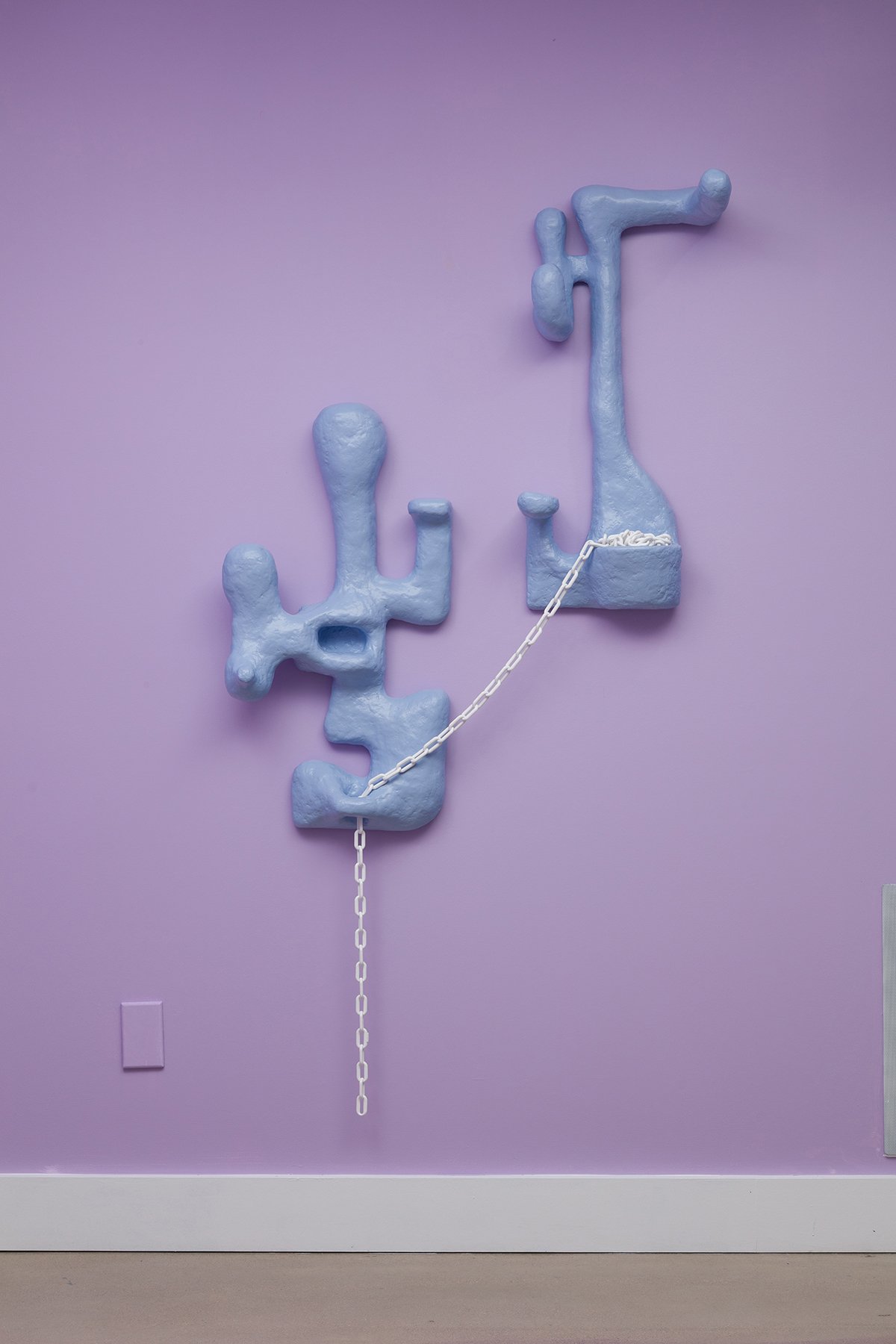

On the left: Amber Cobb, To a Certain Degree, 2022, wood, plaster, paper pulp, and enamel paint, 35 x 19 x 9 inches; on the right: Amber Cobb, To a Certain Extent, 2022, wood, plaster, paper pulp, and enamel paint, 34 x 16 x 11 inches. Image by Wes Magyar.

Cobb’s sculptures, though there are only two, keep the exhibition from appearing too uniform and bleed her imagined world into the viewer’s realm. The artist also uses her sculptures as an extension of her paintings, with their color, shape, and texture mimicking the flat, painted world she has created. They emphasize the message of boundary crossing and questioning of the grid with their similarity to a written language. Positioned close together, the sculptures even seem in conversation, echoing the communication of the closely positioned characters in Cobb’s paintings and bleeding into the viewers’ space. This conversation was at one time accentuated by a chain connecting the sculptures, though the chain was stolen early in the exhibition due to it being in a public and unguarded exhibition space. [1]

Three works by Amber Cobb, from left to right: To a Certain Degree, 2022, wood, plaster, paper pulp, and enamel paint, 35 x 19 x 9 inches; To a Certain Extent, 2022, wood, plaster, paper pulp, and enamel paint, 34 x 16 x 11 inches; and Solo Ride, 2022, gouache on wood panel, 20 x 20 inches. Image by Wes Magyar.

Cobb’s work is pleasurably meddlesome, toying with the restrictions of the grid while situating itself within the grid’s systematic order and easing viewers’ ability to ingest visual information. She presents irregularly shaped characters alongside complex ideas about systems, highlighting the role of art in making plain difficult ideas while remaining pleasing. Her understanding of these ideas establishes her as not just an artist but a teacher, one who can dissect even the most complicated ideas into discernable bites of relevant, enjoyable art.

Danielle Cunningham (she/her) is an artist, scholar, and independent curator. She writes about science fiction, gender, sexuality, and disability, with an emphasis on mental illness. The co-founder of chant cooperative, an artist co-op, she holds a master’s degree in Art History and Museum Studies from the University of Denver.

[1] From my conversation with the artist on September 24, 2022.