Sing Our Rivers Red & Merciless Indian Savages

Sing Our Rivers Red

Dairy Arts Center, 2590 Walnut (26th & Walnut) Boulder, Colorado 80302

May 12, 2021-October 30, 2021

Curators: Danielle SeeWalker and JayCee Beyale

Admission: $5 Suggested Donation

Gregg Deal (Pyramid Lake Paiute): Merciless Indian Savages

History Colorado Center, 1200 N. Broadway, Denver, CO 80203

Aug. 14, 2020-July 18, 2021

Admission: Adults: $14, Seniors (65+): $12, Students (16-22 with valid student ID): $10, Children (5-15): $8, Children 4 and under & Members: Free.

Review by Emily Zeek

On Indigenous People’s Day in 2019, a mural by the artist LMNOPI was unveiled on the back of the Dairy Arts Center in Boulder. It depicts a young Shoshone woman: the artist, actor, and dancer Sarah Ortegon. The executive director of the Dairy was so moved by the imagery she wanted to do more to raise awareness of Indigenous experiences within mainstream culture. In 2021, the Dairy is now tackling the difficult issue of colonial settler violence and abuse, specifically against Native women, with Sing Our Rivers Red—an exhibition about Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, #MMIW. [1]

LMNOPI, Uncounted, 2019, mural at the Dairy Arts Center in Boulder of the Arapaho Shoshone artist, actor, and activist Sarah Ortegon with a topographical map of the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming. Image by Emily Zeek.

Due to the heavy subject matter of the exhibition, which addresses the abuse, violence, and suffering of over 5000 missing and murdered Indigenous women, the space feels ceremonial and much like a sanctuary. The curators, Danielle SeeWalker and JayCee Beyale, have facilitated a place for spiritual contemplation. SeeWalker, a citizen of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe in North Dakota, explains, “my family and I have been personally affected by the MMIW epidemic, and that is what drew me to put so much passion and energy into curating this exhibit.” [2]

A portion of the installation Sing Our Rivers Red by Tanaya Winder, Jaycee Beyale, and Danielle SeeWalker, 2015-2021, burlap, yarn, and single earrings donated from 2015 to 2021, 40 x 3 feet. Image by DARIA.

The Sing Our Rivers Red exhibition has been travelling since 2015 when it was launched by Tanaya Winder, who comes from an intertribal lineage of Southern Ute, Pyramid Lake Paiute, and Duckwater Shoshone Nations, where she is an enrolled citizen. [3] It “strives to raise consciousness, unite ideas, and demand action for our Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit relatives who have been taken, tortured, raped, trafficked, assaulted, and murdered.” [4]

Danielle SeeWalker, MMIW, 2019, acrylic on canvas, 24 x 36 inches (left), Iná na chinca, Mother and Child, 2020, acrylic, aerosol, oil pastel on canvas, 24 x 36 inches (right). Image by DARIA.

Several components of the Sing Our Rivers Red exhibition add to the evocative narrative of the trauma and suffering of Native women in distinct ways. The main gallery features an installation of thousands of separated earrings representing each of the missing and murdered Indigenous women. There are also clothes designed by Patricia Michaels and Danielle SeeWalker, sand art by JayCee Beyale, and reflective paintings that give a face to trauma. In addition, there is a spoken audio component by Tanaya Winder titled Extraction and an area where those impacted by this crisis can add their feelings and thoughts to a memorial wall. In the hallway, there are more paintings and a large mural by curator JayCee Beyale depicting an Indigenous woman.

Patricia Michaels, Native Fashion Taking Action, part of Michaels’ MMIW Collection, fabric and various materials. Image by DARIA.

In curating the show, Beyale draws on his Navajo background and the traditional practice of weaving by including a “spirit line” that rises into the ceiling. A string of red yarn orients the viewer through the space, signifying the way the issue of violence transcends borders and impacts Indigenous women across the continent. This spirit line, Beyale explained to me in an interview, is included in Navajo textiles and represents an exit for the spirit which animates artworks and textiles. The ghostly, suspended ribbon skirts in the gallery and the fashion designs by Patricia Michaels—some draped with chains—become visceral images of suffering, not unlike the way depictions of a suffering Christ in Catholic churches add to the holy symbolism of those spaces. Meanwhile, Beyale’s large mural in the hallway of the event space is imposing, conveying a sense of protection.

JayCee Beyale, Matriarch, 2021, acrylic wall painting. Image by DARIA.

One of the primary weapons of colonial violence enacted on communally-oriented Native American tribes in the past was the act of separation. This includes the disturbing history of boarding schools that separated children from their parents. [5] In Colorado in particular, the U.S. government also attempted to disrupt tribal communal land ownership in the 1890’s by offering individuals in the Ute tribe parcels of land to try to “domesticate” Natives through farming. [6] These violent acts of separation continue on into the present and are represented most poignantly in the exhibition by the individual earrings missing from their other halves. These earrings become a metaphor for the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women who have been separated from families due to domestic violence, abuse, sex trafficking, or drug use.

One of the works in Patricia Michaels’ series Native Fashion Taking Action, part of her MMIW Collection, made of fabric and various materials, with the letter “I” referring to missing and murdered Indigenous women. Image by DARIA.

And the statistics are quite startling. More than four in five American Indian women have experienced violence. One in three Native American women will be raped in their lifetimes, and 86% of missing and murdered cases involving Indigenous people are unsolved. [7] The FBI is tasked with investigating these crimes. Within the bureaucracy of the FBI, they mark these files with a red letter “I” to indicate “Indian” cases. In the exhibition, the artist Patricia Michaels incorporates this imagery of a red letter “I” into one of her works—a dress of a woman carrying a pile of moccasins, each representing a missing woman, into a spiritual dimension.

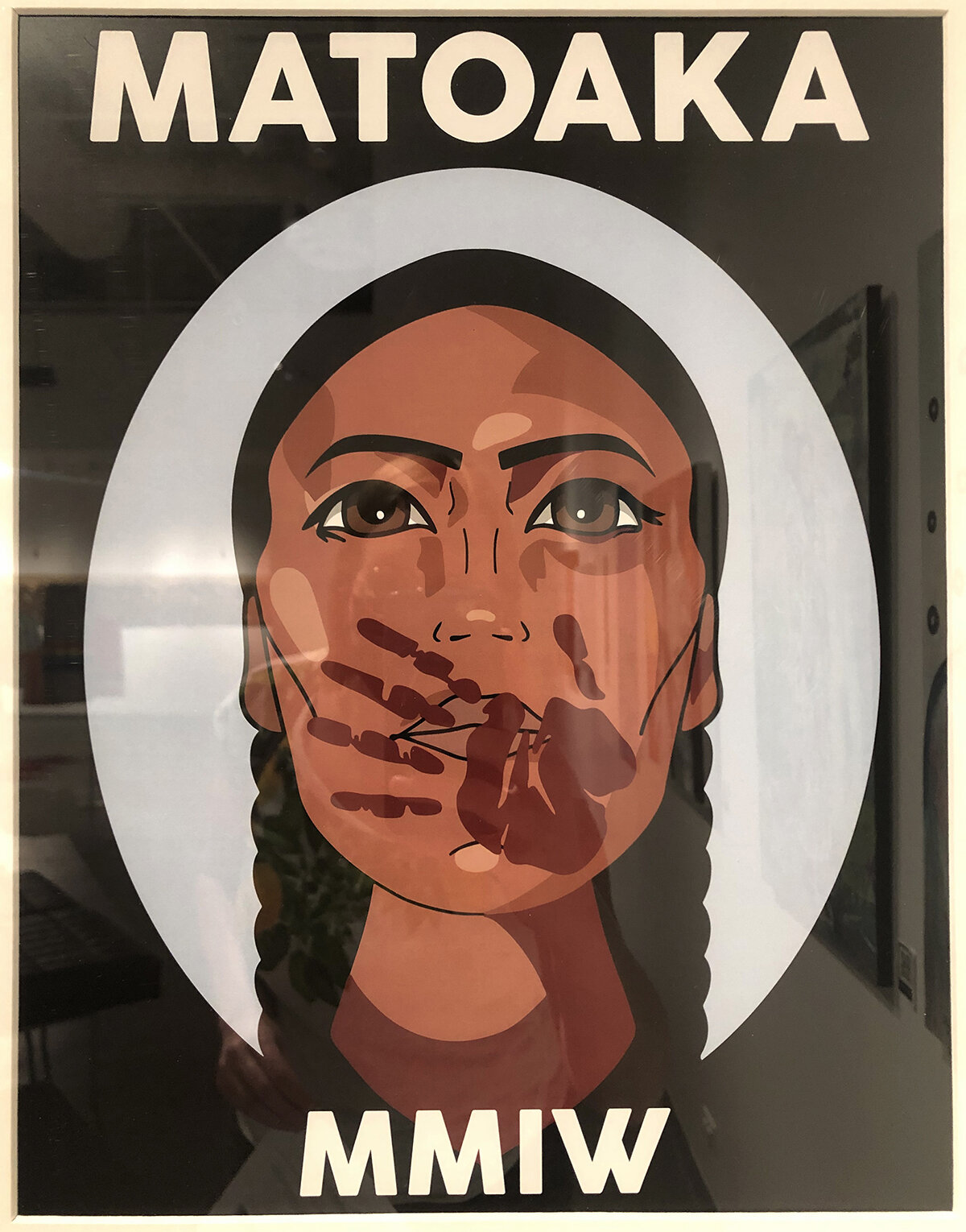

Olivia Montoya, Matoaka, digital illustration. Image by DARIA.

Beyale and other artists in the exhibit are also quick to point out the connections between the abuse of women and the abuse of the land. In fact, it was the exploitative mining practices that European conquistadors brought to the Americas in the 1500s that included enslaving Indigenous people as laborers in mines and in sex trafficking, beginning a tradition of Indigenous exploitation and abuse that continues to this day. [8] Most recently in places like the Standing Rock Reservation in North and South Dakota, where contractors settle into a region to construct pipelines or extract natural resources, Beyale asserts, they enter into Native communities disrespectfully, often exploiting and abusing the women there. [9] As Olivia Montoya notes in her artist’s statement, the historic Native woman Matoaka—known in U.S. popular culture as Pocahontas—was herself a missing Indigenous woman who was captured and enslaved as a young teenager by colonial settlers at Jamestown. [10]

Recently, many socially-conscious, non-Native communities have begun introducing land acknowledgments into their public meetings and events, starting proceedings with a statement about which specific tribes were displaced from the land they occupy. The land occupied by the cities in the Front Range of Colorado is Ute, Arapaho, and Cheyenne land. Beyale, who is Navajo, explained to me in my interview that while the land acknowledgments are a nice “gesture” from settler colonial communities, they can come across as an “empty sorry”—something that doesn’t disrupt the status quo but rather enables it and plays into white guilt.

Suspended in the McMahon Gallery at the Dairy Arts Center: Danielle SeeWalker, Donna ChrisJohn, and Akalei Brown, Ribbon Skirts, 2021, cotton materials and ribbon on skirts of various sizes for women and girls. On the floor: Jaycee Beyale, Untitled, 2021, sand painting. Image by DARIA.

What is required, he pointed out, are steps beyond merely acknowledging the traumas and abuse that Native people have experienced for the benefit of the white supremacist, patriarchal power structure, but reparations for harm done. That is why the Dairy Arts Center is creating a permanent community space for Indigenous people. While the space is small in comparison to the amount of land that has been stolen from Indigenous communities in Colorado and throughout this nation’s history, Beyale hopes that it will continue to give a platform to those like himself who are shedding light on the Indigenous experience within settler societies.

In addition, Beyale notes that decolonizing our perspectives from the predominantly white male narratives that have been violently imposed upon Americans for centuries helps to “separate the signal from the noise” regarding the Indigenous experience. At the History Colorado Center in Denver, Beyale’s friend and colleague Gregg Deal, a contemporary artist and member of the Pyramid Lake Paiute tribe, picks up on this theme in his exhibit Merciless Indian Savages. In the wall text for this provocative exhibition, Deal poses the question, “What does it mean to communicate an Indigenous message when to do so effectively means speaking through filters of capitalism, nationalism, and mainstream American culture?”

A view of Gregg Deal’s solo exhibition Merciless Indian Savages on display at the History Colorado Center. Image by Katie Bush of History Colorado.

With the exhibition title, Deal is drawing attention to a passage in the U.S. Declaration of Independence that refers to Indigenous people as “merciless Indian savages” (perhaps a projection considering the brutal, genocidal campaign of dehumanization embarked upon by colonial settlers). Deal contrasts stereotypical images of Native people in cartoons with punk lyrics, drawing parallels between power struggles that also transcend cultural boundaries and borders.

While some romanticize the founding fathers as rebels, Deal has a more sobering take on these icons. “They were mass murderers,” he explained in a phone interview regarding his work. “George Washington was one of the biggest slave owners in Virginia. I think that the idea of fighting for freedom works if you're actually fighting for freedom. They were not fighting for freedom.” Deal went on to describe the disturbing actions taken by George Washington and those under his command when they burned the winter reserves of the Seneca people of upstate New York and skinned Natives from the waist down, then took those skins to a bootmaker to make them into boots. [11]

Gregg Deal, The Hearts of the Children, acrylic on wood panel. Image by Katie Bush of History Colorado.

In Colorado, disturbing settler colonial history and Indigenous trauma is often overlooked by predominantly white communities. One such instance of brutality is the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, when as many as 500 Indigenous people, including women, children, and elders, were slain by a cavalry of 700 soldiers in order to make room for settlers, ranchers, and gold miners. [12]

Deal’s work is contemporary—a departure from the traditional aesthetics of many Indigenous artists, which Deal states is a conscious choice on his part. He is frustrated with the commodification of his culture, asserting that “Native art tends to be controlled by a western market…I want to be able to express myself in a contemporary language and I see that aesthetic as sort of low hanging fruit, something that appeals to the settler colonizer marketplace.”

Gregg Deal, Protect Our Elders, posters, on display at History Colorado Center. Image by Katie Bush of History Colorado.

Instead, Deal appropriates some of the imagery he detests—the stereotypical images of caricatured Native Americans in popular culture and photographs of Indigenous people taken by the ethnographer Edward Curtis. He adds a semiotic touch by inserting statements like “Existence as Protest” into the imagery. Deal also exposes contradictions inherent in a so-called democratic nation founded by slave owners and genocidal leaders by collapsing narratives in one particularly interesting work regarding COVID and protecting elders. Deal explains,

“If you look at the way history is taught between the Plains Indian wars in the mid-1800s all the way up until you can say Standing Rock, there has almost been no question as to what Native people are. Everybody believes that this is what they look like, this is what they sound like, this is what color their skin is, this is how they dress, this is how they talk. You know, all of those things are sort of part of that stereotype and backing up against those things seems to shock this generational idea of Indigenous existence and oftentimes even challenges…their perception…even challenges whether or not…we're alive or not. I think any contemporary Native artist is contesting that and is struggling with that in some way, whether you're going with it or you're going against it.”

The biographical panel and other works in Gregg Deal’s solo exhibition Merciless Indian Savages on display at the History Colorado Center. Image by Katie Bush of History Colorado.

The burden of having to prove your existence—through art or any means—is a heavy one to bear and one that non-Native artists and communities could do better to share, whether that is through land acknowledgments, reparations of space, or in other ways. However, often settler colonial culture covers up or ignores Indigenous history to comfort white egos, which tend to create a segment of the population and artists who are out of touch with contemporary dialogues of justice, power, and oppression.

Suffering and spirituality can be intrinsically linked and when generations of people have suffered for white comfort, it's Indigenous artists that bear the burden of colonial trauma whose work has the spiritual upper hand. Despite this, it is not uncommon to see white artists within settler colonial cultures describe their process in spiritual and downright holy terms, even referring to their work and process as healers. But creating art as white people within settler colonial cultures is a fraught endeavor when the land carries a history of genocide.

The power in Deal’s work and the Sing Our Rivers Red exhibition is the beauty of solidarity with those who have suffered. Through these works of art, viewers gain a pathway to understanding the troubling issues that undermine the spiritual foundation of this region. “One thing that America has a really difficult time doing is reconciling their own actions.” Deal points out, “They expect everybody to fall in line with the ideal but they themselves do not take accountability for their actions.”

Emily Zeek is a transmedia and social practice artist from Littleton, Colorado who works with themes of feminism, sustainability, and anti-capitalism. She has a BFA in Transmedia Sculpture from the University of Colorado Denver and a BS in Engineering Physics from the Colorado School of Mines.

[1] The artists included in the exhibition are JayCee Beyale, Akalei Brown, Donna Chrisjohn, Gregg Deal, Crystal Dugi, Patricia Michaels, Olivia Montoya, Jonathan Nelson, Mary Jane Oatman, Sarah Ortegon, Lakota Sage, Danielle SeeWalker, Nathalie Standingcloud, and Chad Yellowjohn. The hashtag #MMIW is used on social media to raise awareness of the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women and as part of the movement to combat the violence against Native women and to find those who are missing. For more information, see https://www.nativewomenswilderness.org/mmiw.

[2] From the Sing Our Rivers Red exhibition informational pamphlet.

[3] Ibid.

[4] From the exhibition wall text.

[5] For more information on the history of boarding schools that Native American children were forced to attend see https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=16516865.

[6] To learn more about this shameful chapter of Colorado history, see the exhibition Written on the Land: Ute Voices, Ute History at the History Colorado Center, 1200 N. Broadway, Denver, CO 80203.

[7] From the statistical information displayed on a screen outside of the main gallery where the Sing Our Rivers Red exhibition is on display.

[8] See UnPacked: History Talks from History Colorado, https://www.historycolorado.org/unpacked-history-talks-history-colorado, and Andrés Reséndez: The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (New York: Mariner Books, 2016).

[9] From my interview with JayCee Beyale.

[10] From the Sing Our Rivers Red exhibition informational pamphlet.

[11] See https://www.onondaganation.org/history/us-presidents-hanadagayas/ for the Onondaga tribe’s account of Washington’s violence.

[12] A video recounting this terrible event titled Fort Collins Before: Native Americans, with historian Ron Sladek and Fort Collins Museum Educational Curator Treloar Tredennick, from April 28, 2016, is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dQYZ4Sbvlgo.