A Faint Light

Deborah Dancy: A Faint Light

Robischon Gallery

1740 Wazee Street, Denver, CO 80202

March 31-May 29, 2021

Admission: Free

Review by Emily Zeek

We all have that friend—someone whose speech seems to pollute the atmosphere with self-absorption. We care about them, sure, but how can we gently point out their narcissism? The pseudo-spiritual millennial term for this behavior is “toxic,” referring to both unhealthy people and the relationships we have with them. But what about our relationship with our colonial past—could it be described as “toxic?”

In her current solo exhibition A Faint Light at Robischon Gallery, artist Deborah Dancy depicts a particular form of pastel-laced colonial toxicity through a visual metaphor of abstraction. Using Rococo-period figures, collages, found objects, and a color palette of putrid yellows and smoky charcoal, Dancy delves into toxic friends and our toxic past, gently pointing out both the literal and cultural pollution we create as individuals and collectively.

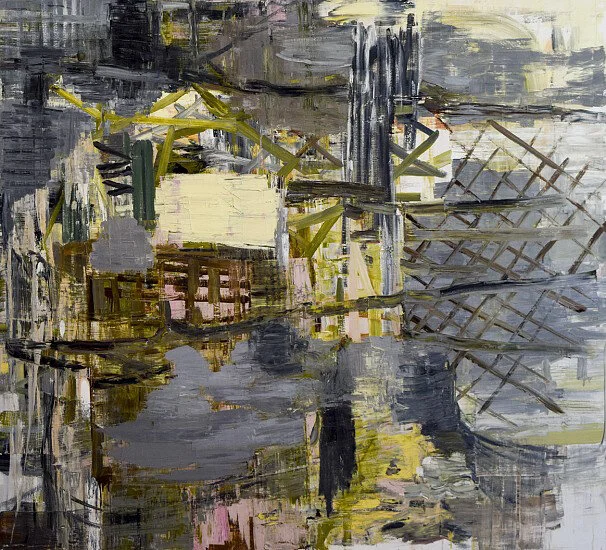

Deborah Dancy, Trade Route, 2019, oil on canvas, 70 x 64 inches. Image courtesy of Robischon Gallery.

Dancy employs multiple media in the thirty-seven works in the exhibition in order to bring together the chaos of abstract expressionism and the decadence of the colonial American version of the Rococo—whose opulence necessitated exploitative practices like slavery—with the soot and pollution of the Anthropocene—the geologic period shaped by human intervention. The artist has referred to her creations and process as “a beautiful mess” and she incorporates a certain ironic and humorous worldview into her works while mining these messy histories. [1]

In Faint Light—a collection of abstract oil paintings on canvas and acrylic on paper—and Oblivion—a mixed media series that includes collages and sculptures from found objects and paint, Dancy pays homage to several different moments in U.S. and European art history. From Jeff Koons’ porcelain sculptures, to Jackson Pollock’s abstract drips [2] and Helen Frankenthaler's watery compositions, to even the surrealists’ play with squiggles and unconscious autonomous movements, the works feel intellectually and historically grounded while still airy, fresh, and contemporary.

Deborah Dancy, Some of This and Some of That, 2018, oil on canvas, 70 x 64 inches. Image courtesy of Robischon Gallery.

The Faint Light series of paintings is the main focus of the exhibition. Dancy’s unique color palette in these works is muted, made up of layers of creams and whites with musty yellows and puke greens alongside sweeter lavenders and pinks. The term “faint” in the title seems like an appropriate double entendre that refers equally to a sense of diminutive subtlety and a general feeling of faintness, nausea, and unease.

Intersecting her queasy pastel reveries is a dark grey charcoal that speaks to a particularly urban, Anthropocene presence. The paintings also have a notable texture of grit due to Dancy’s use of crushed stone on the surface of works like The Weight of a Million Black Stars #5 & #6. Webs and grids evoke tribal organic configurations that are blotted out with what could be interpreted as smoke, pollution, or even cement. The springtime hopefulness and exuberance of the lavenders and pinks are destined for interference by a menacing thunder cloud or smokestack.

Deborah Dancy, The Weight of a Million Black Stars #6, 2019, acrylic and black crushed stone on paper, 50 x 38 inches. Image courtesy of Robischon Gallery.

A close-up image of Deborah Dancy, The Weight of a Million Black Stars #6, 2019, acrylic and black crushed stone on paper, 50 x 38 inches. Image by Emily Zeek.

With the Oblivion series, Dancy juxtaposes the abstracted paintings with overtly political themes. These mixed media collages and sculptures call attention to the toxicity of the American legacy of dehumanization. For Dancy, who was born in Alabama to an African American family and raised in Chicago [3], these critical themes are quite poignant and timely.

Deborah Dancy, Queen in Her Own Mind, figurine with steel wool, cotton balls, and rubber snake, 11. 5 x 9 x 7 inches. Image courtesy of Robischon Gallery.

Deborah Dancy, Monument, hand-painted plaster figure gilded with paint, glitter, decorative ornaments, and rubber mice, 16.5 x 6.5 x 6.5 inches. Image courtesy of Robischon Gallery.

In one of the most iconic and sardonic works of the exhibition, Dancy super glues together pieces of cotton to make a flowing gown for a porcelain figurine. The figure is accompanied by another sculpture of a dandy gentleman on a pedestal of silicon rats. The white porcelain of the figurines contrasts with the cotton residue of slavery and could trigger a white person’s white fragility; in fact, the porcelain is a perfect symbol of the fragile ego of racism.

Deborah Dancy, Just Desserts, oil paint residue and porcelain heads in glass compote dish, 10 x 10 x 6 inches. Image courtesy of Robischon Gallery.

By taking both a historical and environmental Anthropocene approach to society, Dancy’s work is brave and confrontational. In Just Desserts, Dancy piles up paint residue into a glass compote dish. Here the materiality and physicality of paint becomes a metaphor of indulgence and the opulent waste of the privileged class, which also includes artists. But in her grace and artistry Dancy acts as a valuable friend who can shine a light on character deficiencies in an aesthetic and beautiful way.

A passive observer might miss the nuances Dancy illuminates in this exhibition, but that’s part of the delicate balancing act commercial galleries like Robischon must take on when they show this work. With overtly political art Dancy risks insulting the very class of gentry who can afford her work but who may also be the most complicit in our climate of both actual and metaphorical pollution.

Deborah Dancy, Oblivion 15, mixed media collage, 14 x 11 inches. Photo Courtesy of Robischon Gallery.

It’s as if Dancy is creating work for the Marie Antoinette in all of us, putting up a mirror to our privileges and our callous self-absorption that is quite literally destroying our planet. In Oblivion 15, Dancy elegantly collages together a colonial debutante with an abstract plume of charcoal smoke emanating from her mouth. The symbolism could not be more direct—our toxic friend, back at their bullshit.

Emily Zeek is a transmedia and social practice artist from Littleton, Colorado who works with themes of feminism, sustainability, and anti-capitalism. She has a BFA in Transmedia Sculpture from the University of Colorado Denver and a BS in Engineering Physics from the Colorado School of Mines.

[1] https://www.deborahdancy.com/news

[2] Dancy’s work graces the walls of the United States Embassy in Cameroon, linking her to a legacy of American diplomacy that used the vehicle of abstract expressionism— and specifically the work of Jackson Pollock—to propagandize American ingenuity, capitalist freedom, and intellectual domination during the Cold War. See Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom and the Cold War (Chicago: U. of Chicago Press, 1985).