Dark Archive

elin o’Hara slavick: Dark Archive

GOCA Downtown

Plaza of the Rockies, Suite 100

121 S. Tejon Street, Colorado Springs, CO 80903

September 2-October 8, 2022

Admission: Free

Review by José Antonio Arellano

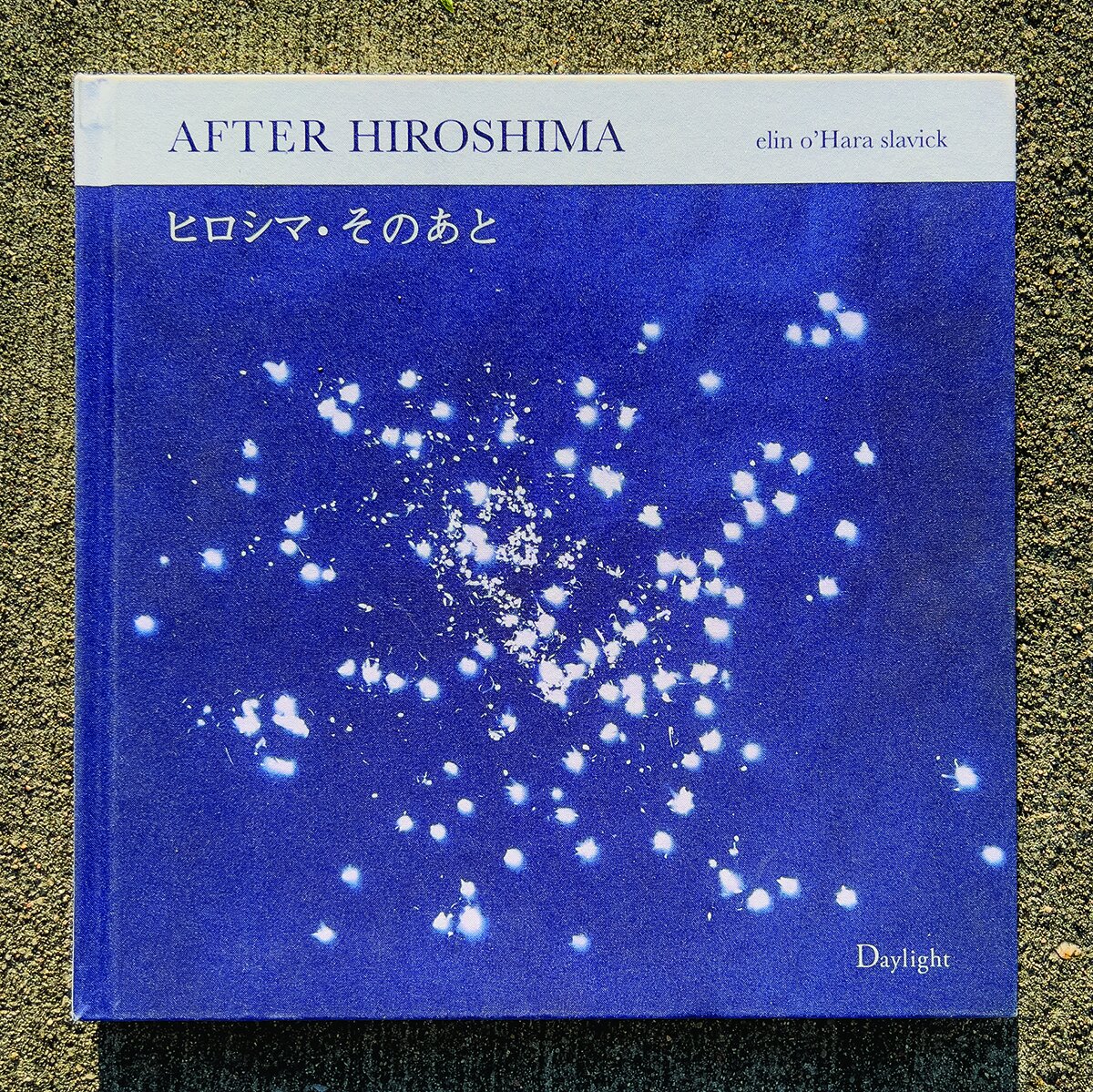

When I learned that elin o’Hara slavick would have a solo exhibition at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs (UCCS) Galleries of Contemporary Art (GOCA) Downtown, I purchased two of her books: Bomb After Bomb: A Violet Cartography (2007) and After Hiroshima (2013). Unprompted, my eight-year-old daughter tells me, “I like this book,” as she points to it and calls it “the pretty blue one.” Of all the books arrayed on our table that day, she had singled out and looked through After Hiroshima, the cover of which reproduces one of slavick’s cyanotypes.

The cover of elin o’Hara slavick’s book After Hiroshima (2013) featuring slavick’s work Hiroshima Flowers, 2008, cyanotype of dead Hiroshima flowers, Hiroshima, Japan. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

In the indigo blue of Japanese work wear, the cover appears to capture sparks of burning iron oxide—the white-hot shimmering stars of a hand-held sparkler. To quote Maggie Nelson quoting Goethe, “We love to contemplate blue, not because it advances to us, but because it draws us after it.” [1] And it does—they do, these cyanotypes, drawing us toward the fields of blue and stark white voids that capture the presence of absence.

A view of elin o’Hara slavick’s exhibition Dark Archive at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs (UCCS) Galleries of Contemporary Art (GOCA) Downtown, with photochemical drawings titled There Have Been 528 Atmospheric Above Ground Nuclear Tests To Date. Image by Tom Kimmell, courtesy of UCCS GOCA.

This invitational impulse constitutes part of slavick’s strategy to create visually arresting work that draws us in while simultaneously pointing to something outside itself. Most of the work in the Dark Archive exhibition is informed by the practice of photography and its irreducible connection to the objects and light that make photographic images possible.

elin o’Hara slavick, Fire Tree, 2008, silver gelatin contact print of a rubbing of a tree that survived the atomic bombing in Hiroshima in 1945. Image courtesy of the artist.

slavick not only uses photographic materials in almost all of the pieces on display, including paper collages made on film holders and photochemical drawings made with film developer on photo paper, the work also references what is called indexicality. Her photographic contact prints of rubbings of atomic-bombed trees are connected to those trees in a one-to-one relationship—they “index” the trees as my footprints index my steps or as smoke indexes fire.

elin o’Hara slavick, top left: Vieques Island, Puerto Rico, U. S., 1941-1999; top right: Hypocenter in Hiroshima, Japan, 1945; lower left: We Are Our Own Enemy, Alamogordo, New Mexico, U.S., 1945; lower right: Johnston Atoll, U.S., 1958-1962, acrylic, graphite, gesso, ink watercolor, gouache, and ink on Arches paper. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Even the displayed colorful drawings, although conceptually representative and not indexical, each correspond to a site bombed by the U.S. [2] What looks like the shimmer of light and life in the image that captured my daughter’s attention is made by the shadows of dead Hiroshima flowers, a simultaneously beautiful but undeniably bleak reminder of the “death shadows” of atomic warfare. [3]

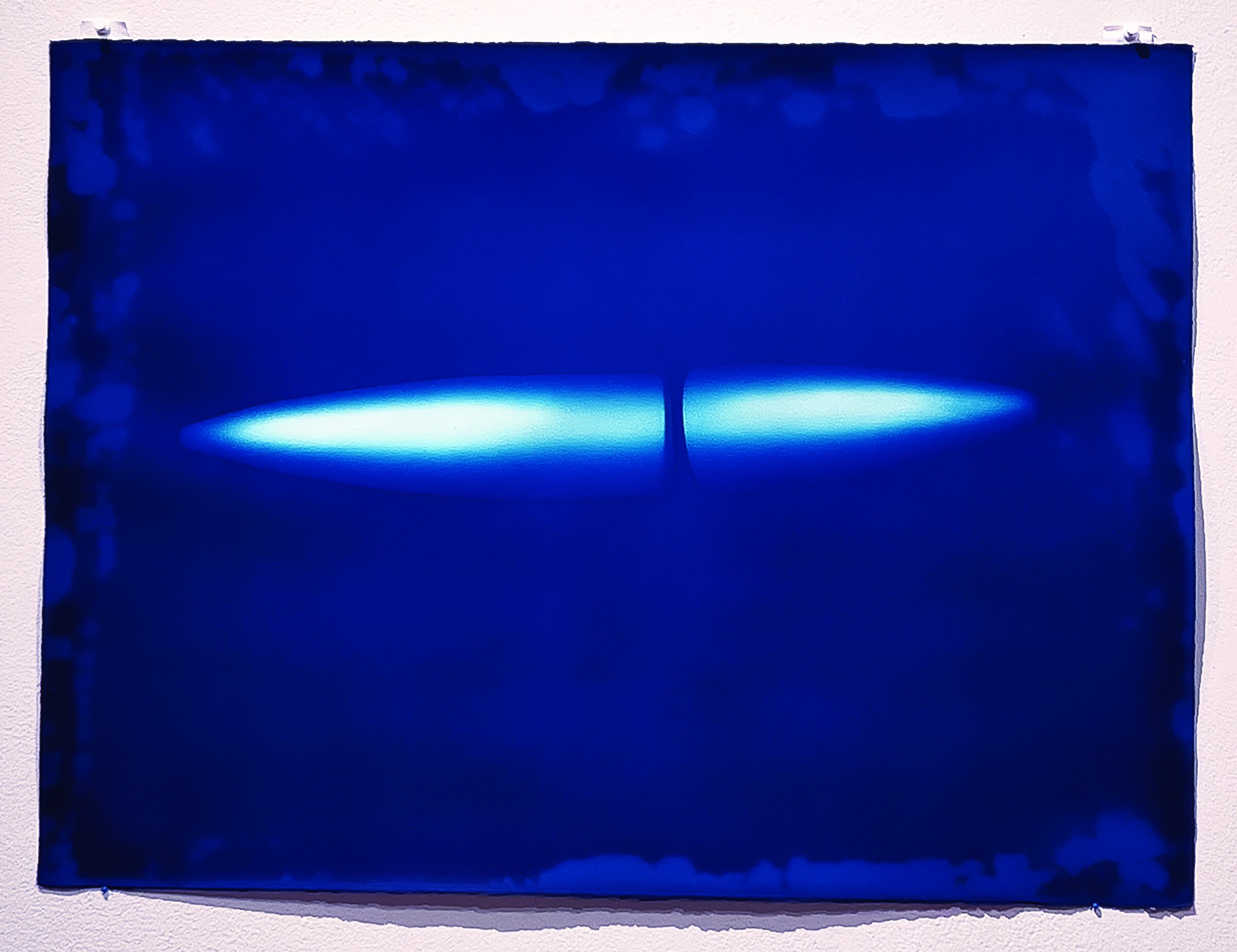

elin o’Hara slavick, Hibakusha (A-Bombed) Tree, Hiroshima, 1 and 2, 2018, framed solarized silver gelatin prints. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Through slavick’s work, I learned that photography and the discovery of uranium’s radioactivity share a history in the work of physicist Henri Becquerel. Becquerel detected radiation via the accidental exposure of a photographic plate by a piece of uranium. [4] The current exhibition explores this relationship in two solarizations of two of the 60 trees that survived the bombing of Hiroshima. A bright flash of light is required to make this type of image, a process that, in slavick’s hands, reminds us of the blinding flash of the August 6, 1945 Hiroshima bomb.

elin o’Hara slavick, far left top and far right bottom: Molecular Model I and II, 2022, cyanotypes of archival materials in the Caltech Archives, 11 x 14 inches each; far left bottom and far right top: Carl Anderson's Geiger Counter parts (used in 1930s in his 7 inch cloud chamber) I and 11, 2022, cyanotypes of archival materials in the Caltech Archives, 11 x 14 inches each; left and right of center: Rocket Missile Heads I and II, cyanotypes of archival materials in the Caltech Archives, 2022, 24 x 32 inches each; center: Drosophila Illustrations by Edith Wallace, 2022, cyanotype of transparencies of illustrations in the Caltech Archives, 24 x 32 inches. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

The cyanotypes in After Hiroshima, a selection of which are on display at GOCA, are made by the shadows of a few of the radiated objects that were hit by the atomic blast—objects now preserved in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. More recent cyanotypes of missile heads— some of the million produced at Caltech during World War II—are displayed alongside cyanotypes of Caltech plastic molecular models and Edith M. Wallace’s drosophila drawings of mutated insects exposed to radiation.

elin o’Hara slavick, Sky Atlas Collage (Robert Oppenheimer), collage created using only materials from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) on an archival Sky Atlas photograph from the Caltech Palomar Observatory, 14 x 14 inches. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

slavick just completed an artist residency at Caltech (the California Institute of Technology) where she had access to abandoned darkrooms. She found boxes containing forgotten pictures, including some featuring Albert Einstein on a beach holding a marionette of himself, Robert Oppenheimer posing with developing atomic technology, and Sky Atlas photographs from the Caltech Palomar Observatory. “It felt like the whole world was in those boxes,” she said during an exhibition walk-through. As an institution that was crucial for the development of atomic technology, Caltech is a microcosm of our post-1945 universe.

elin o’Hara slavick’s Sky Atlas Collages on display at GOCA Downtown. Image by Tom Kimmell, courtesy of UCCS GOCA.

The abandoned darkrooms thus become the titular “Dark Archive,” wherein we might catch what Jacques Derrida calls “archive fever”—the unending desire, aided by developing technology, to return to the origin of it all. [5] To view the fragments of such an archive, in the form of 14 x 14-inch contact print photographs made from abandoned glass plates, is to intuit a sense of profound connectivity. In slavick’s collages, pictures of stars and planets become experiments in formal abstraction that highlight a relationship among forms.

A view of works representing nuclear tests in the year 1958 from elin o’Hara slavick’s series There Have Been 528 Atmospheric Above Ground Nuclear Tests To Date, 2022, developer and fixer (photo chemical) drawings on outdated/fogged silver gelatin paper left at Caltech in the Sky Atlas processing room, variable dimensions from 8 x 10 inches to 20 x 24 inches. Image by Tom Kimmell, courtesy of UCCS GOCA.

If the exhibition is itself a kind of archive, it is indeed a dark one. GOCA displays 528 photochemical drawings made using abandoned, fogged photographic paper which slavick found in the Caltech darkrooms. Each of the drawings represents each of the 528 above-ground detonations of atomic bombs tested throughout the world since the 1940s. Arranged chronologically, the photochemical drawings collectively offer an affecting visualization of what can only be the disastrous health effects of unleashed radiation. I imagine the emission of each blast radiating out, connecting us all, as I look for the images grouped together showing detonations from the year of my birth.

elin o’Hara slavick speaking at the opening reception for her exhibition Dark Archive at GOCA Downtown on September 2, 2022. Image by Tom Kimmell, courtesy of UCCS GOCA.

When my daughter looked through After Hiroshima, did she see the reproduced stills of Akira Iwasaki’s film Hiroshima-Nagasaki, August 1945? Did she see the pictures of a Japanese child’s hand, the same size as her own, that had been burned so violently it fused into a single mass? These images are included in the book by the art historian James Elkins to demonstrate the crucial distinction between art and presentation—between representation and re-presentation. Such images of the child’s hand, Elkins tells us, “are unavailable for, or as, art.” [6]

elin o’Hara slavick, Leaf from a Second Generation A-Bombed Chinese Parasol Tree, 2009, silver gelatin contact print from a rubbing of the leaf, Hiroshima, Japan. Image courtesy of the artist.

Those of us who experience these images “tend to forget they are representations.” Elkins’ use of the word “representation” here is misleading because his point is that a photograph of a mutilated body is not a representation of it as a painting, by necessity, would be. “What counts as art, here, is work that can be seen as representation.” [7] Elkins’ deictic “here” points to slavick’s work, which exists as art even as it re-presents via indexicality. Her use of indexicality connects us to our world, but as art her photographs gesture to a world without war. She is not simply documenting; she is prompting us to imagine.

elin o’Hara slavick, Rocket Missile Heads II, cyanotypes of archival materials in the Caltech Archives, 2022, 24 x 32 inches. Image by José Antonio Arellano.

Perhaps some might claim that slavick comfortably aestheticizes the pain of others for her own gain. We might even misquote Theodor Adorno, who at one point argued that “poetry” after Auschwitz “was barbaric.” [8] Such criticism of art existing after unspeakable, criminal tragedy risks misunderstanding the role of the artist in the world and the work of art as art. If everything is indeed connected, we could find the violent in the beautiful and the beautiful in the violent. To find beauty in the violent is not to negate its reality, but to allow an opportunity to become attuned to its nature. In slavick’s work, we might recognize our own capacity to enact violence as well as our ability to refrain from it.

José Antonio Arellano is an Assistant Professor of English and Fine Arts at the United States Air Force Academy. He holds a Ph.D. in English Language and Literature from the University of Chicago. He is working on two manuscripts titled Race Class: Reading Mexican American Literature in the Era of Neoliberalism, 1981-1984 and Life in Search of Form: 20th Century Mexican American Literature and the Problem of Art.

[1] Maggie Nelson, Bluets (Seattle: Wave Books, 2019), 4.

[2] See elin o’Hara slavick, Bomb after Bomb, a Violent Cartography (New York: Charta, 2007), with a foreword by Howard Zinn.

[3] “Death shadows” refers to the imprints of persons, etched into stone, caused by the atomic blast.

[4] See elin o’Hara slavick, After Hiroshima (Durham, NC: Daylight Books, 2013), 28.

[5] Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

[6] James Elkins, “On an Image of a Bottle,” After Hiroshima, 12.

[7] Elkins, 13.

[8] Theodore Adorno’s quotation, which I often misremembered as “To write a poem after Auschwitz is impossible,” is actually “To write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric.” https://www.marcuse.org/herbert/people/adorno/AdornoPoetryAuschwitzQuote.htm.