Dirty South

Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse

Museum of Contemporary Art Denver

1585 Delgany Street

Denver, CO 80202

September 16, 2022-February 5, 2023

Curated by Valerie Cassel Oliver

Admission: Adults: $10, College Students, Teachers, Seniors, and Military: $7, Members and Children 18 and under: free

Review by Emily Zeek

Growing up in Eufaula, Oklahoma, my friend John Hill remembers taking manners classes in school. [1] He was taught how to treat people with respect and how to keep the focus on the parents when their kids were misbehaving. Hill is an “OG” Southerner, part of the Mvskokee tribe that is from the area of what is now Alabama. But his ancestors were pushed northwest to reservations in Oklahoma by the Trail of Tears. A sister city in Alabama shares the same name as his hometown Eufaula. [2]

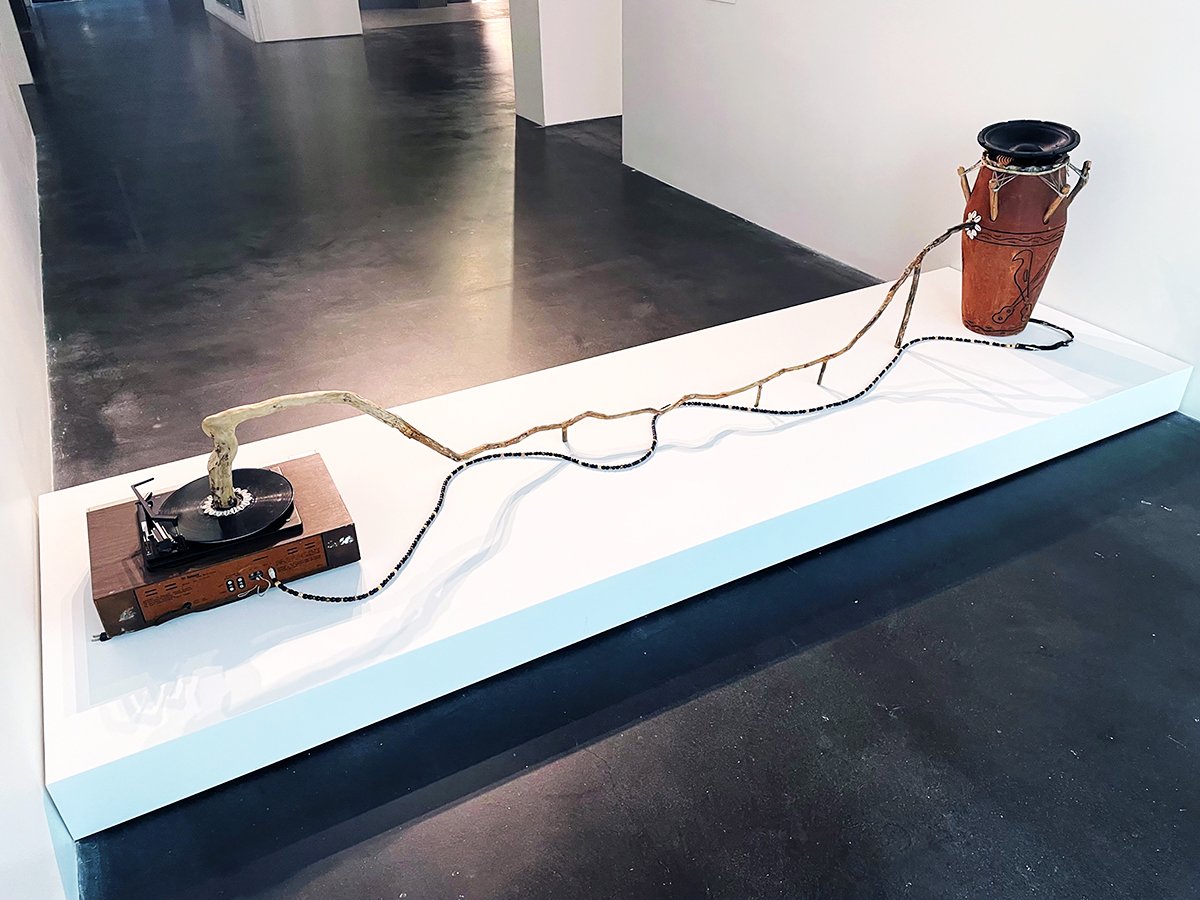

A view of works on display in Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. On the left: Kevin Sipp, Take It to the Bridge, 2009, found wood, turntable, vessel, and mixed media. On the right: RaMell Ross, Caspera, 2019, inkjet print mounted on dibond. Image by Wes Magyar.

Because of its geographic proximity, culture in Oklahoma is shaped by Texas’s enormous influence and Southern dispositions. Particularly, Hill grew up listening to the Houston-based hip-hop pioneer DJ Screw as a teenager and connected with the message of struggle that was beginning to express itself through hip hop music in the South.

DJ Screw took the innovative step of chopping and slowing down cassettes to create a distinctive sound that still influences hip-hop and pop musicians to this day. [3] “Counter to what people think, his music was about peace and bringing people together,” Hill explains, “that’s what DJ Screw was trying to do.” [4]

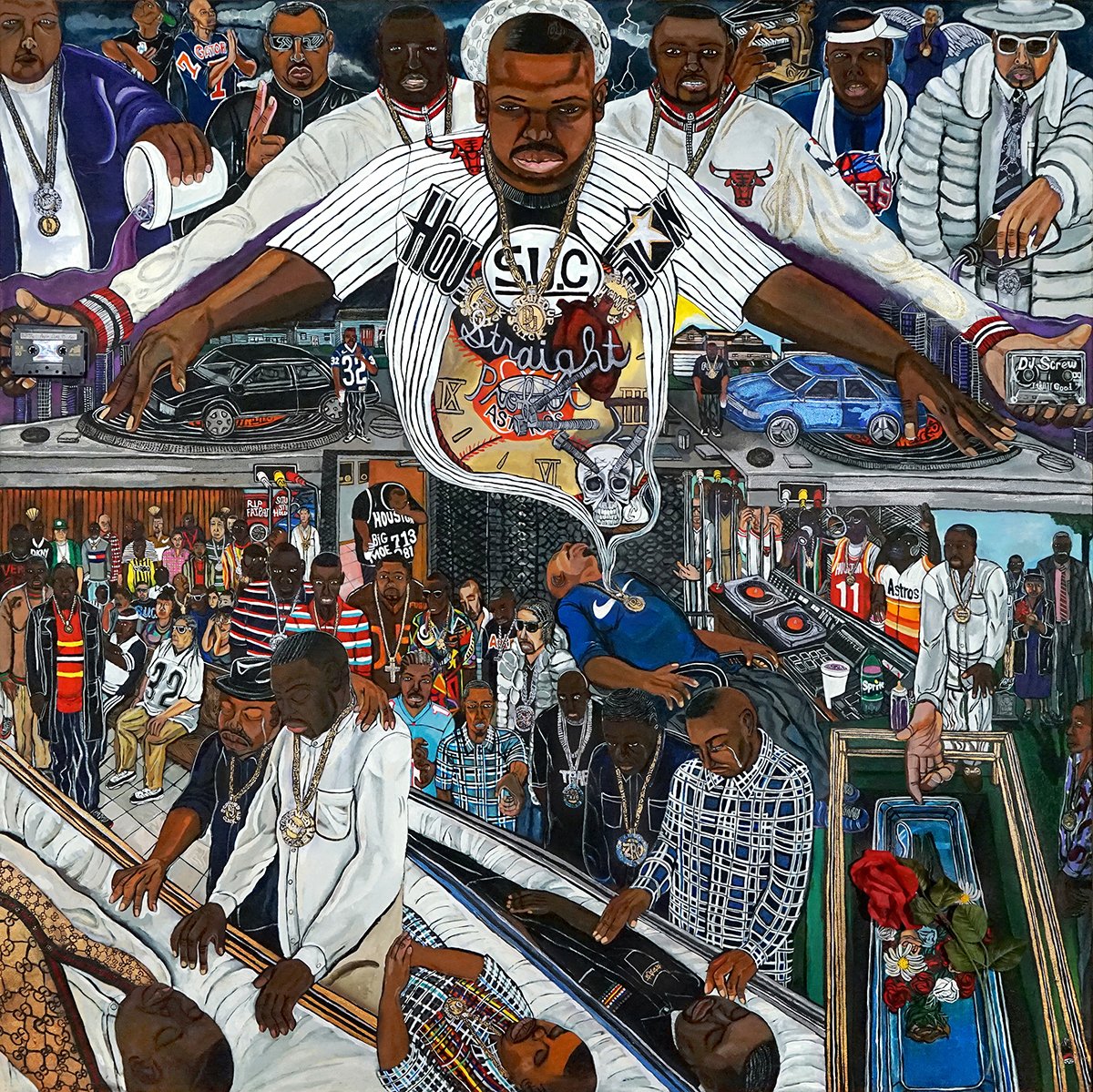

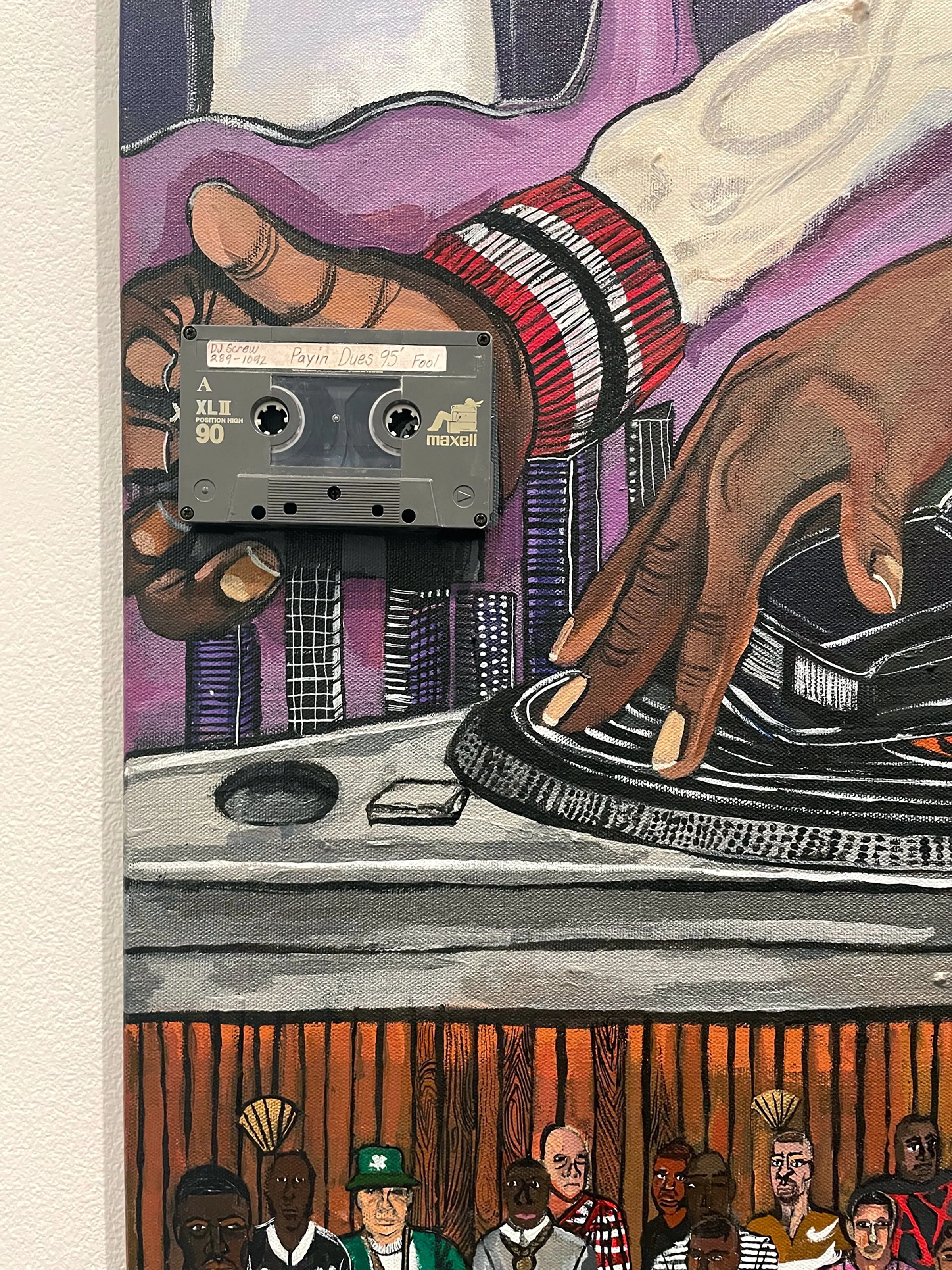

El Franco Lee II, DJ Screw in Heaven 2, 2016, acrylic on black canvas with cassette tape and silk rose. Image courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver.

Curator Valerie Cassel Oliver has been excavating these misunderstood but important distinctions in Southern material and sonic culture since she worked at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. Her groundbreaking exhibition Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse is currently on view at the Denver Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) through February 5th.

An installation view of works on the lower level of the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver in the Dirty South exhibition. Image by Emily Zeek.

The show at the MCA is a touring version—modified and abridged—of the exhibit by the same name that appeared last year at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA). [5] Among the works on view at the MCA is a one of DJ Screw’s iconic mixtapes and a painting by El Franco Lee II, DJ Screw in Heaven 2, depicting his funeral and many of the early hip-hop luminaries looking on as he DJ's from heaven. The coroner’s report listed the cause of death of DJ Screw (whose given name was Robert Earl Davis Jr.) as an overdose from codeine, a popular ingredient in “lean”—the preferred drink of fans of his music. [6]

In recent years, Cassel Oliver has been on the forefront of contemporary art curators of African American art. Cassel Oliver now works as the Sydney and Frances Lewis Family Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the VMFA and has found in the director, Alex Nyerges, a collaborator in collecting.

Nyerges explains, “it is the strategic mission of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts to be one of the three best collections of African American art.” [7] From a place of privilege as a white man, he has set a personal mission of “bringing African American art into the mainstream.” [8]

Works in the Dirty South exhibition on display on the second level of the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, with Rita Mae Pettway’s Housetop (Fractured Medallion), 1977, corduroy, on the right. Image by DARIA.

When Cassel Oliver was a senior curator at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, the bones of the Dirty South show started revealing themselves to her. But it wasn’t until she landed her current role at the VMFA that her vision finally materialized.

The exhibit at the VMFA was well received by the art community and got a favorable write-up in the New York Times, where critic Holland Cotter referred to it as a “big, juicy thought-through thematic sampler.” [9] And for anyone who’s spent time in New England, you know it’s no easy feat getting a Connecticut-born, Harvard-educated Northerner to say something positive and reflective about the South.

In fact, it’s this lingering, pervasive distaste for the South that persists in the American psyche that Cassel Oliver is countering by elevating Black artists and the culture that shaped them. In doing so, she has maintained the geographic integrity of the South, including as far West as Texas and as far north as Tennessee, but has broken up the region conceptually. The three floors of the MCA reflect these different components of Black southern cultural experience from Cassel Oliver’s standpoint: “Landscape” on the ground floor, “Religion” on the second floor, and “The Black Body” on the lower level.

A still image of Allison Janae Hamilton’s Wacissa, 2019, single-channel video. Image by Emily Zeek.

Nathaniel Donnett, I looked over Jordan and what did I see; a band of angels coming after me, 2017, florescent light, wood, roofing shingles, machete, glass, and acrylic paint. Image by DARIA.

When you walk into the exhibit on the main floor, you are immediately transported to Florida by Allison Janae Hamilton’s immersive video work she created by dragging a video camera through the Wacissa River. The work, entitled Wacissa, brings attention to the flora of the Southern landscape and the injustices of the history there: the Wacissa River was part of Florida’s Slave Canal.

In the South, there is no simple plant, material, or environment that stands alone to be reviewed without a context of violence. A physical section of a shotgun style shack, by artist Nathaniel Donnett, not only has violence baked into the name “shotgun,” but a blue glow illuminates a subtext of illicit activities, and a machete hangs in one of the windows.

Kaneem Smith, The Past is Perpetual/Weighted Fleet, 2012, reclaimed cotton bale, vintage iron hanging scales, bailing wire, and wood palette. Image by DARIA.

Kevin Sipp, Take It to the Bridge, 2009, found wood, turntable, vessel, and mixed media. Image by DARIA.

As the show continues into the next room, a bushel of cotton is framed by weighing measurements and tools in a work by Kaneem Smith titled The Past is Perpetual/Weighted Fleet. The choices of these works give a glimpse into the psychological ubiquity of power and domination that weighs heavily on the consciousness of the South.

But Cassel Oliver, in selecting Kevin Sipp’s Take it to the Bridge, relieves some of this tension and provides a vent for the sticky heat of oppression. The work visually links the sonic impulses of hip-hop with those of African rhythms and drums, bearing witness to the liberatory nature of self-expression and music.

Renee Stout, She Kept Her Conjuring Table Very Neat, 1990, mixed media. Image by DARIA.

A view of Rodney McMillian’s installation From Asterisks in Dockery, 2012, vinyl, thread, wood, paint, and lightbulb. Image by DARIA.

Upstairs, the show continues to explore transcendence and spirituality. Various syncretic traditions are on display including an altar by Renee Stout, She Kept Her Conjuring Table Very Neat, and a stitched red vinyl replica of a wooden chapel that many credit as the birthplace of the blues (located on Dockery Farm in Mississippi) in a work by Rodney McMillian called From Asterisks in Dockery.

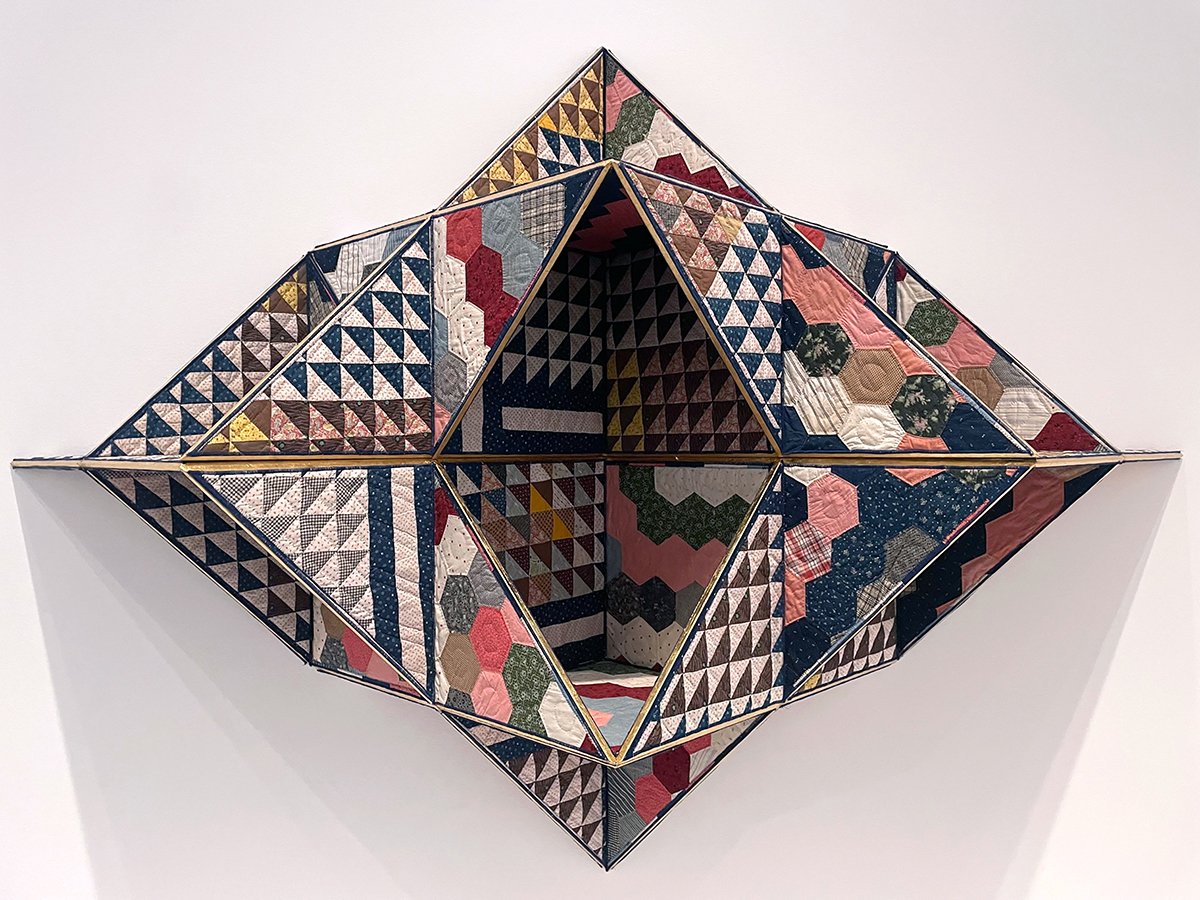

Sanford Biggers, Khemestry, 2017, antique quilt, birch plywood, and gold leaf. Image by DARIA.

Rita Mae Pettway, Housetop (Fractured Medallion), 1977, corduroy. Image by DARIA.

Geometry makes a satisfying appearance in Rita Mae Pettway’s Housetop, a vibrantly pulsating corduroy quilt with a pattern meant to trap evil, and Sanford Biggers’ Khemestry, a sculptural, wall-mounted work of golden hues, sacred geometry, and quilted hexagons.

Felandus Thames, Just Hanging, 2014, fat-lace shoestrings and vintage shoes. Image by DARIA.

An installation view of the “Cabinet of Curiosities” on the lower level of the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver in the Dirty South exhibition. Image by Wes Magyar.

A cobweb-shaped work made of fat-lace shoestrings and vintage shoes by Felandus Thames, Just Hanging, introduces the downstairs section, “The Black Body.” But despite the spooky introduction, the works downstairs in the subsection “Cabinet of Wonders” are optimistic and playful. The “Flower Suit” worn by Ceelo Green, who hails from Atlanta, and a stage outfit worn by James Brown (born in South Carolina) are displayed alongside a guitar played by Bo Diddly (born in Mississippi) as well as album artwork and posters promoting the afro-psychedelic musician Sun Ra (born in Alabama though he claimed to be from Saturn).

The “Flower Suit” worn by Ceelo Green for the November 11, 2015, performance of “Music to My Soul” on the television program The X Factor UK. Image by Emily Zeek.

The intent behind Cassel Oliver’s show is to contextualize the “sonic impulse” of the South. In fact, as Cassel Oliver explains in the exhibit introduction, “the expression ‘Dirty South’ is codified within the culture of southern hip-hop music.” One of the first uses of the term comes from a song by the Atlanta-based hip-hop group Goodie Mob, which included a young Ceelo Green. Their lyrics are overtly political and explicit: “See life's a bitch then you figure out; Why you really got dropped in the Dirty South.” [10]

Atlanta today is one of the most influential cultural centers in popular music, with multi-platinum artists like Ludacris, Ciara (who now calls Denver home, at least part time, thanks to her husband Broncos quarterback Russell Wilson), B.o.B, Outkast, Young Jeezy, and T.I. [11] But the popularization and mainstream evolution of Southern hip hop has included important free speech milestones from all over the South.

Notably, in 1990, the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida ruled that 2 Live Crew’s third album, Nasty as They Wanna Be, which set the bar for dirty lyrics, was “legally obscene.” The producer Uncle Luke faced prison time. Later overturned by the Federal Court, a trial acquitted the musicians and the case set a precedent for the free speech protection of explicit lyrics. [12]

A detail view of El Franco Lee II’s painting DJ Screw in Heaven 2, 2016, acrylic on black canvas with a cassette tape. Image by DARIA.

Defying the polite programming of Southern culture and being able to speak one’s mind regardless of how dirty, raunchy, or taboo that might be is the legacy of Southern hip-hop. Oppressive power dynamics typically force people into the double bind of polite inauthenticity on one hand or direct honesty perceived as rudeness on the other. Yet it is the responsibility of power structures to secure and protect the free speech of everyone, not just rich and powerful white people, which is why cultural institutions like the MCA and VMFA have a mandate to take on this work.

However, as museums and cultural institutions continue to decolonize, they can lag behind popular culture, applying soft power and the rules of curatorial standards to subtly censor the more obscene and explicit facets of oppressed people’s experience. So, while the Dirty South exhibit provides context to those outside the South about the material culture and sonic impulse of hip-hop and other genres of southern music, as a whole the show still may feel too clean, polished, and stuffy to truly embody the label “dirty.” Let’s just say there’s no explicit warning label on this exhibition despite its titillating title that would lead you to assume otherwise.

A detail view of El Franco Lee II’s painting DJ Screw in Heaven 2, 2016, acrylic on black canvas with a silk rose. Image by DARIA.

The realities of drug dealing, gang violence, hyper-masculinity, and even just the prevalence of obscenities is conspicuously missing from the exhibit. This could be a reflection of the power structures at play in cultural institutions. [13] Or it could be as Southerners, it may be difficult to shake all those manners classes.

But just as the trajectory of hip-hop has continued to press the limits of free speech and expression, it will be interesting to witness Cassel Oliver’s career trajectory and the subsequent iterations of this material. Will shows become more explicit, grittier, and in your face, true to the evolution of boundary-breaking hip-hop? Or, like so many aspects of the Black cultural experience, will gentrification and erasure whitewash the grit out of the “Dirty South?”

There is an opportunity here to continue the process of excavation in the area of free speech by including taboo socio-economic realities and language to illustrate the successes that may belie the expectations of dominant systems of white supremacy. Hip-hop has cleared the path, museums just need to go down it.

Emily Zeek (she/her) is a transmedia and social practice artist from Littleton, Colorado who works with themes of feminism, sustainability, and anti-capitalism. She holds a BFA in Transmedia Sculpture from the University of Colorado Denver and a BS in Engineering Physics from the Colorado School of Mines.

[1] From my conversation with John Hill.

[2] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eufaula,_Alabama and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eufaula,_Oklahoma.

[3] From Hip Hop Evolution, directed by Darby Wheeler & Rodrigo Bascunan, Canada: Banger Films and Netflix, 2016-Present.

[4] From my conversation with John Hill.

[5] From the exhibit text.

[6] “DJ Screw: From Cough Syrup to Full-Blown Fever.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, November 11, 2010: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2010/nov/11/dj-screw-drake-fever-ray.

[7] These Alex Nyerges’ quotes come from the video “Curator's Talk: The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse” that took place on May 20, 2021, from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TddE4_Q-Kzo. You can see more works from the full VMFA exhibition in this video.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Cotter, Holland. “Art Meets Its Soundtrack Deep in 'the Dirty South'.” The New York Times, July 15, 2021: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/15/arts/design/dirty-south-virginia-museum-of-fine-arts.html.

[10] Lyrics to Goodie Mob’s “Dirty South”: https://www.flashlyrics.com/lyrics/outkast-feat-goodie-mob/dirty-south-55.

[11] See Darren E. Grem, “‘The South Got Something to Say’”: Atlanta’s Dirty South and the Southernization of Hip-Hop America,” https://southernstudies.olemiss.edu/media/Grem_OutKast-Article.pdf.

[12] From Hip Hop Evolution, directed by Darby Wheeler & Rodrigo Bascunan, Canada: Banger Films and Netflix, 2016-Present.

[13] Over the last several years, a more concerted effort has been made to challenge the viability of donors with troubling connections embedded within racist and exploitative capitalist systems. See Peggy McGlone, “The Sacklers Have Donated Millions to Museums but Their Connection to the Opioid Crisis Is Threatening That Legacy,” The Washington Post, WP Company, February 15, 2019: https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/the-sacklers-have-donated-millions-to-museums-but-their-connection-to-the-opioid-crisis-is-threatening-that-legacy/2019/02/13/d5b47bac-2e39-11e9-86ab-5d02109aeb01_story.html.