Visual Reality: Redefining Artistic Experience through Technological Innovation

Visual Reality: Redefining Artistic Experience through Technological Innovation

Artworks Center for Contemporary Art

310 N. Railroad Avenue, Loveland, CO 80537

January 10–March 1, 2025

Admission: free

Review by Stephen Shugart

Visual Reality: Redefining Artistic Experience through Technological Innovation, now on view at the Artworks Center for Contemporary Arts in Loveland, presents us with thoughtful, sometimes weighty, and sometimes wry examinations of the exhibition's theme. It features works by several of the Artworks Center’s members and is their 2025 biennial exhibition.

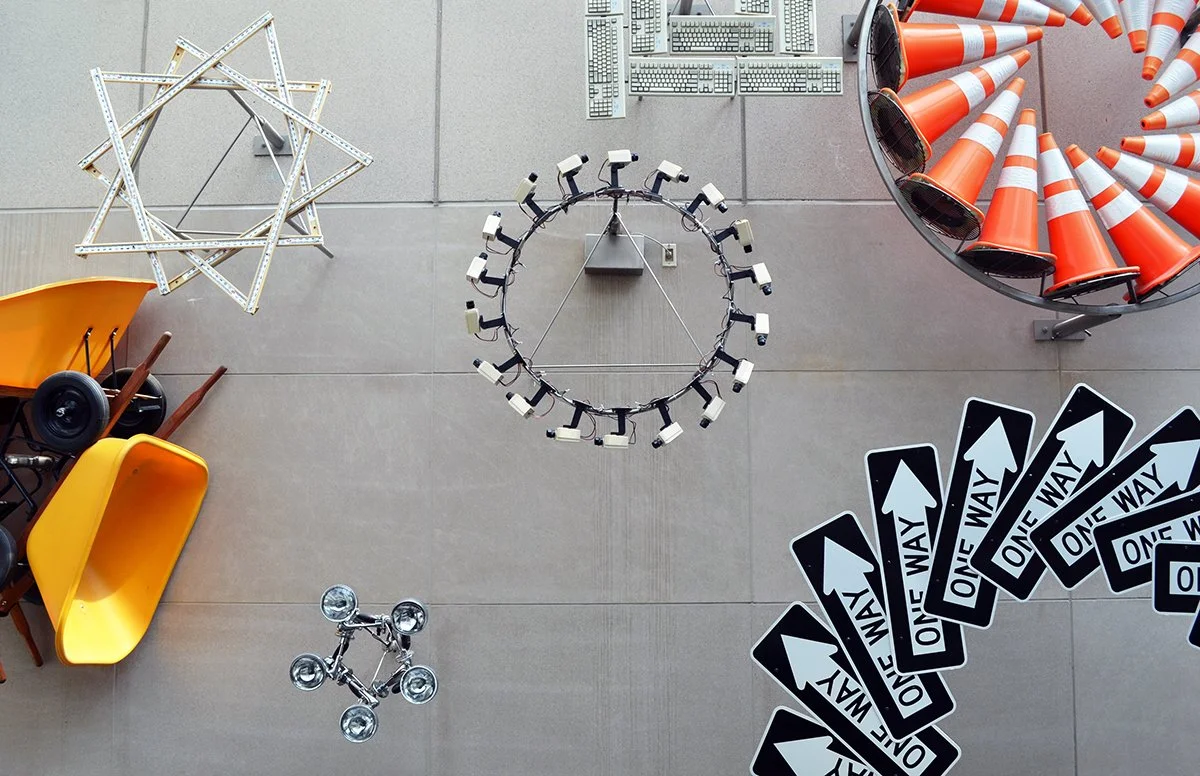

An installation view of Visual Reality: Redefining Artistic Experience through Technological Innovation at Artworks Center for Contemporary Art. Image by Stephen Shugart.

We enter the Center’s intimate gallery space, curated by Elizabeth Suriani, the Center’s exhibition curator, to encounter shimmering aluminum butterfly wings and abstract videos flickering and morphing. There are works of personal memory enhanced by software and artworks that focus on subject matter that reminds us how far we have come technologically from past historical eras. Some question the use of technology altogether.

Brian Kane, Future Archaeology, 2024, brushed aluminum print. Image by Stephen Shugart.

Technology as Subject Matter: Commenting On and Critiquing Technology

Brian Kane’s subtly humorous anachronisms, Future Archeology, are three brushed aluminum prints depicting imagined, seemingly Mesoamerican scenes. It takes a minute to register what is happening in these scenes. The inhabitants stand in front of large circular stone monuments with mysterious carved symbols and geometric patterns. However, the universal wifi symbol is centered predominantly in the middle of these large stone circles.

Brian Kane, Future Archaeology, 2024, brushed aluminum print. Image by Stephen Shugart.

The inhabitants are apparently standing around reading what might be stone tablets, but then we notice these have the size and shape of iPads and iPhones. Perhaps the statue is where a wifi signal is the strongest or comes from? These large stone monuments seem to reference the Mayan calendar or, as Kane notes in his artist statement, the Rosetta Stone, “indicating a theme of communication or knowledge transmission across time.” [1] Printing these images on brushed aluminum also provides an otherworldly glimmer and we further experience the time dissonance of modern technology and materials when looking at past cultures.

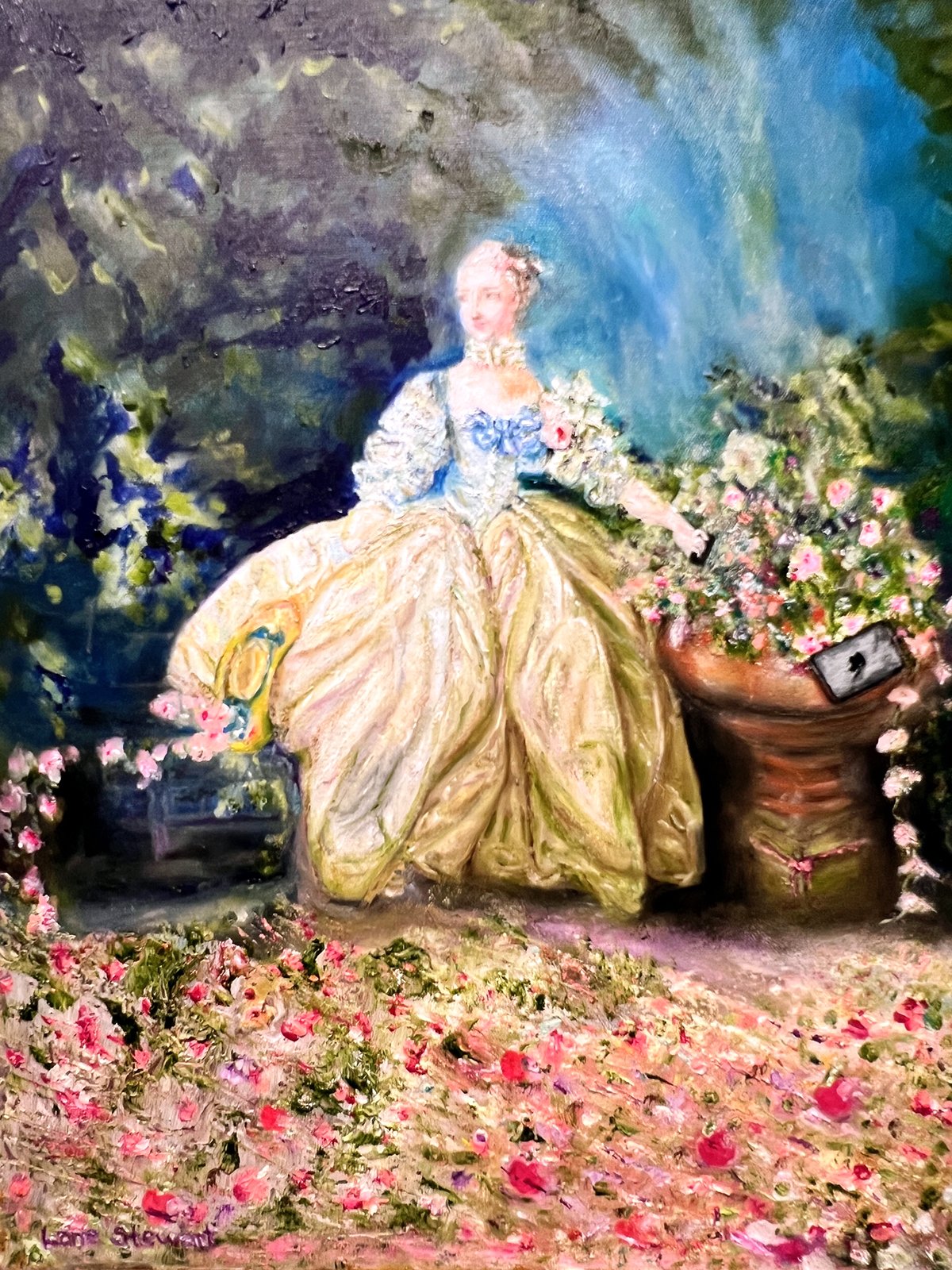

Susan Stuart, Dangerous Liaisons with Social Media, oil on canvas. Image by Stephen Shugart

In a similar vein, Susan Stewart’s Dangerous Liaisons with Social Media is a traditional oil portrait of a young 18th century woman “inspired by François Boucher’s 1716 Madame Bergeret.” [2] Again, we are asked: what if they had modern technology back then? In the painting, the young woman holds a cell phone as she poses by a pedestal overflowing with colorful flowers. An electronic tablet also rests on the pedestal.

Dangerous Liaisons asks us to imagine how smartphones might have affected society centuries ago and how that impossible development would have affected our current era of incessant wireless digital communication. Maybe we’d be robots or some kind of humanoids by now? The painting prompts the viewer to consider this time warp, its cognitive dissonance, and its implications in the subtle 18th century pose. Perhaps a selfie pose in another painting—if Stuart were to pursue a series of paintings like this—might add another twist, further examining our self-absorption which may or may not be similar to high society in the 1700s.

Sylvia Eichmann, Knitting with Cell Phone, old cell phone, bamboo knitting needles, and silk/bamboo yarn. Image by Stephen Shugart.

Sylvia Eichmann’s Knitting with Cell Phone comments on how important human handiwork is no matter the innovation of technology. An old cell phone acts as a spool of yarn supplying material to the knitting needles, which, it seems, are knitting a cozy for the phone. Whatever the relationship, they are connected by organic yarn and there is a suggestion of a possible symbiotic relationship with technology.

An installation view of Visual Reality: Redefining Artistic Experience through Technological Innovation at Artworks Center for Contemporary Art. Image by Stephen Shugart.

The artwork also proposes that when new technology becomes outdated, it can be turned into something new. Even so, as Eichmann notes in her artist statement, while she is perfectly comfortable with technology, she loves creating with her hands using “ancient crafts that involve slow, meditative and repetitive movement.” [3] Knitting with Cell Phone seems to counsel us to take time out from the technological onslaught we live with daily and, ultimately, that technology is simply a tool for artistic vision and human experience.

Ashley Nason, Reclaimed Reservoir, lithographic plate. Image by Stephen Shugart.

Instead of prints, Ashley Nason displays two lithographic plates in this show. Her stark black and white, apocalyptic scenes focus on “the collision of human constructs in nature that contribute to a more fragile environment,” especially in the American West. [4] Dogs, not humans, look on curiously at these imagined scenes that depict makeshift settlements or structures in human-ravaged landscapes, where they are searching for a way “to exist sustainably and in harmony with nature.” [5]

Ashley Nason, Emerging Energy, lithographic plate. Image by Stephen Shugart.

Nason’s eerie efforts to confront and imagine this idea visually is a tall order to convey in works of art, but they challenge us to think about the ramifications of technological progress. She notes in her artist statement that she is less interested in using technology in her work and “more interested in the application of the hand.” [6] The strategy to exhibit the lithographic plates instead of the prints is fitting for the theme of the show and, again, we see that human handiwork is fundamental to art and that technological innovation does not necessarily redefine the artistic possibilities with the tools of technology.

SJ Carlisle, Maker, Carter Lake sandstone with collaged cave painting stencils. Image by Stephen Shugart.

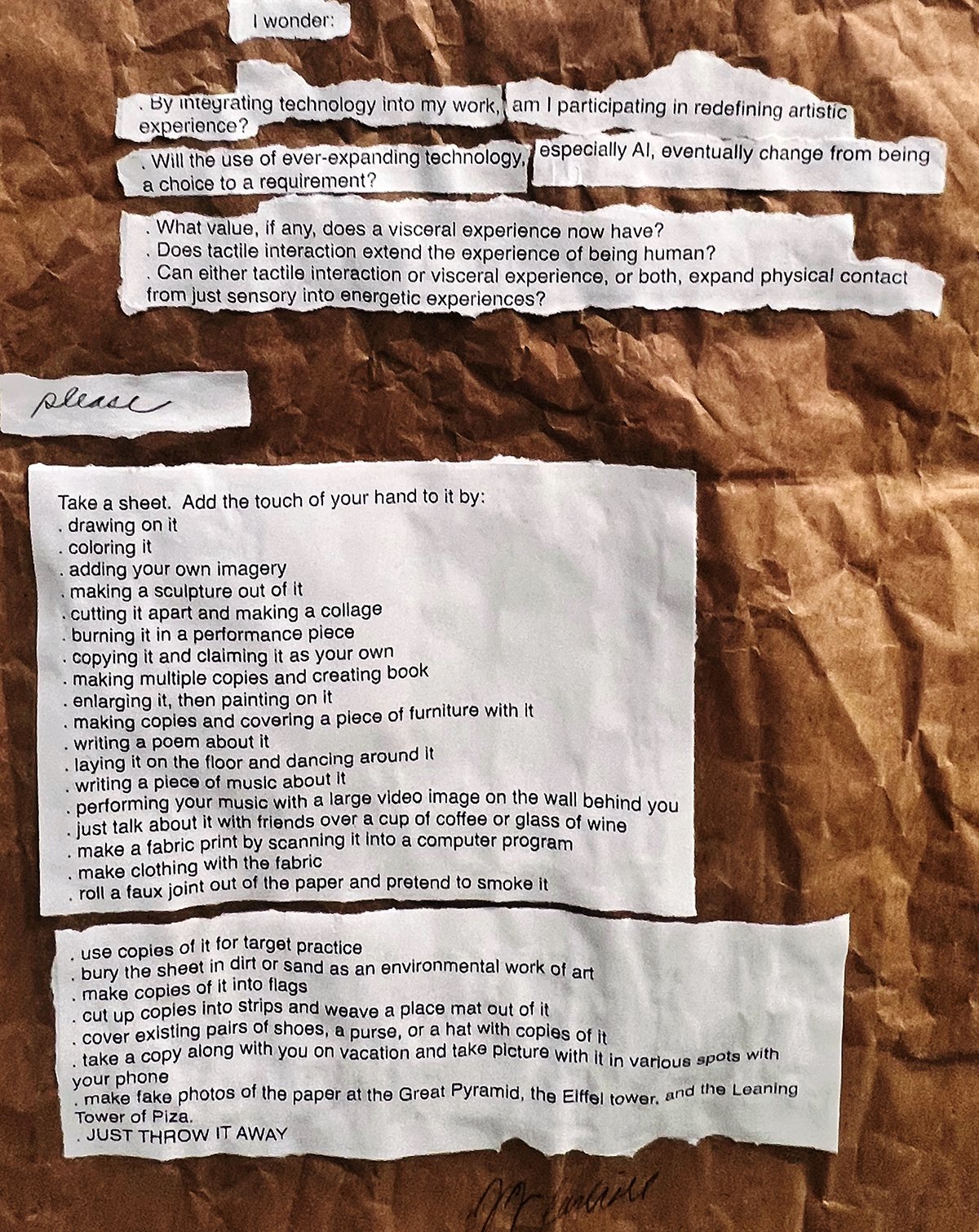

SJ Carlisle’s participatory, multimedia installation of “hand stencils from cave paintings collaged onto Carter Lake sandstone” deeply questions how modern technology seems to invade every part of our modern lives and sometimes seems to threaten the fabric of civilization. [7] She asks, in the torn fragments of paper of her artist statement/poem, “What value, if any, does a visceral experience now have?” [8] The installation includes two hand-painted sandstone fragments from the lake not far from Loveland, using the artist’s stencils of hands from cave paintings.

A detail view of the poem that is part of SJ Carlisle’s Maker. Image by Stephen Shugart.

Mounted on the back of one pedestal is Carlisle’s poem of torn lines of text from the exhibition call and other thoughts she has typed, printed out, and glued to a wrinkled and flattened paper bag, in the style of an anonymous ransom note. But this is not a ransom—it is a plea to the viewer to “add the touch of your hand” to the photocopied images in the shape of hands. [9] She places the photocopies on a pedestal for viewers to take and create something with.

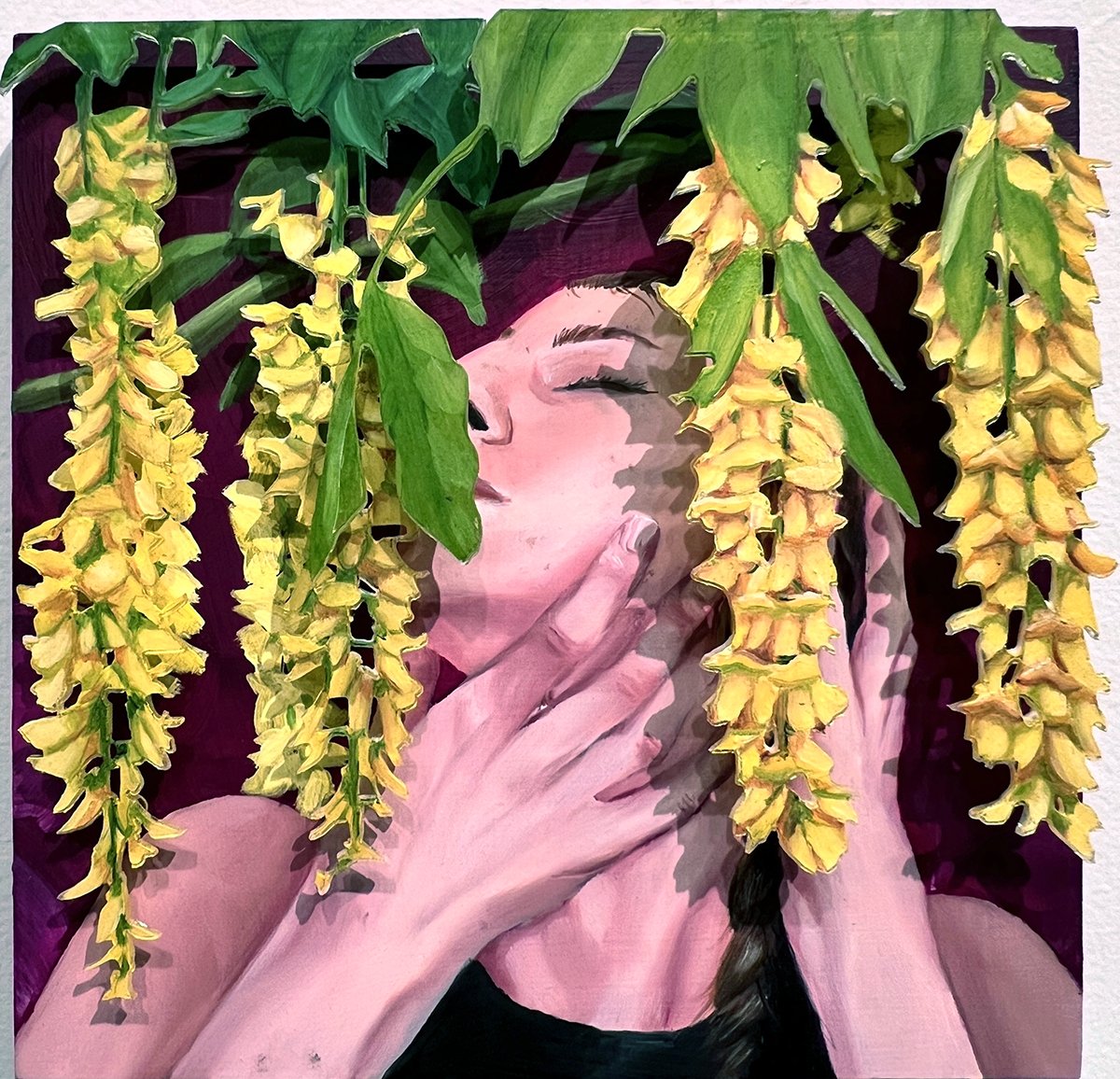

Elizabeth Suriani, Laburnum, oil on canvas, laser cut acrylic plastic relief, and adhesive. Image by Stephen Shugart.

Using Technology to Directly Support the Creation of Art

Other artists in the exhibition focus on using technology to assist in physically creating their pieces. Elizabeth Suriani, in her new series of paintings with poisonous plants, examines “the darker side of the beauty that surrounds us.” [11] She leverages laser-cut plexiglass reliefs to create a three-dimensional viewing experience of a two-dimensional painting, intensifying the painting and giving it a slightly surreal twist. In Laburnum, the artist depicts a woman holding her jaw, with her head turned and eyes closed, while laburnum blossoms and leaves hang over her on the plexiglass planes dangling over the painted canvas.

Elizabeth Suriani, Water Lily, oil on canvas, laser cut acrylic plastic relief, and adhesive. Image by Stephen Shugart.

In all three of Suriani’s works in the show, the plexiglass reliefs of the poisonous plants floating above the painted images imply that the female subjects in the paintings have consumed the plants.

Ana Maria Botero, Relentless Flight (Vuelo Implacable), composite aluminum. Image by Stephen Shugart.

Ana Maria Botero’s Relentless Flight composite aluminum monarch butterflies examine “the delicate balance between nature and technology.” [12] One of the inverted, paper-airplane-like butterflies dangles from the ceiling by steel cables, glinting in the gallery lighting. Another butterfly rests on the floor below as if it has just lit on the ground from flight.

Ana Maria Botero, Relentless Flight (Vuelo Implacable), composite aluminum. Image by Stephen Shugart.

In this work, the modern materials and methods, as Botero explains, “challenge us to consider the intersection of natural survival and technological intervention…and our role in preserving the fragile yet relentless spirit of the monarch's journey.” [13] The contrast of materials and technological shapes of abstracted monarch butterflies create a moment to consider the impact of technology on natural, fragile habitats and the species’ valiant persistence.

Augustus Dallabetta, Camera present (performance), video, steel, and monitor, duration: 6 hours. Image by Stephen Shugart.

Video Art Redefining Artistic Experience

The exhibition includes three video works that investigate the slippery reality of the ubiquitous presence of videos in our modern lives. Augustus Dallabetta’s Camera Present (performance) incorporates footage of a cell phone video into his trippy, thought-provoking, and ultra self-referential multimedia sculpture. The monitor mounted atop a “hand built” rusted steel stand plays a six-hour video of a smartphone videotaping Dallabetta’s construction of the rusted pedestal. [14] This video of a video scrutinizes how the camera itself “creates a performance and distorts reality.” [15]

A detail view of Augustus Dallabetta’s Camera present (performance). Image by Stephen Shugart.

As Dallabetta explains in his artist statement, “The work reveals how the simple act of observation fractures the very reality it seeks to capture…showing how the mere knowledge of being recorded creates a feedback loop that fundamentally alters both the artist’s behavior and the resulting work.” [16] Viewing Dallabetta building and welding his rusted metal stand, we enter a funhouse mirror-like experience. However, stepping back to view the whole piece, the rusted stand grounds the work and us in a very human connection with the artist’s process of fabrication.

Jason Bernagozzi, Persisting more than we ever could be, 2024, dual-channel video. Image by Stephen Shugart.

Jason Bernagozzi’s dual channel video, Persisting more than we could ever be, also addresses the nature of reality and experience. He takes us on a conceptual visual ride via two video monitors hung almost like lovers kissing. Dual channel video is a video presentation format that uses two separate, synchronized channels or screens to display content simultaneously.

An installation view of Visual Reality: Redefining Artistic Experience through Technological Innovation at Artworks Center for Contemporary Art. Image by Stephen Shugart.

As Bernagozzi suggests in his artist statement, the installation, “…depicts lived experience as flow. The data springs out and becomes a living response to the source.” [17] Thus we see mesmerizing and swirling colors of angular and jagged shapes echoing each other back and forth between the two monitors. The artist uses this as a metaphor of language and how it is nothing more than encoding and transmitting abstractions, which, when in a dialogue, “can be something more than we are able to imagine it to be.” [18]

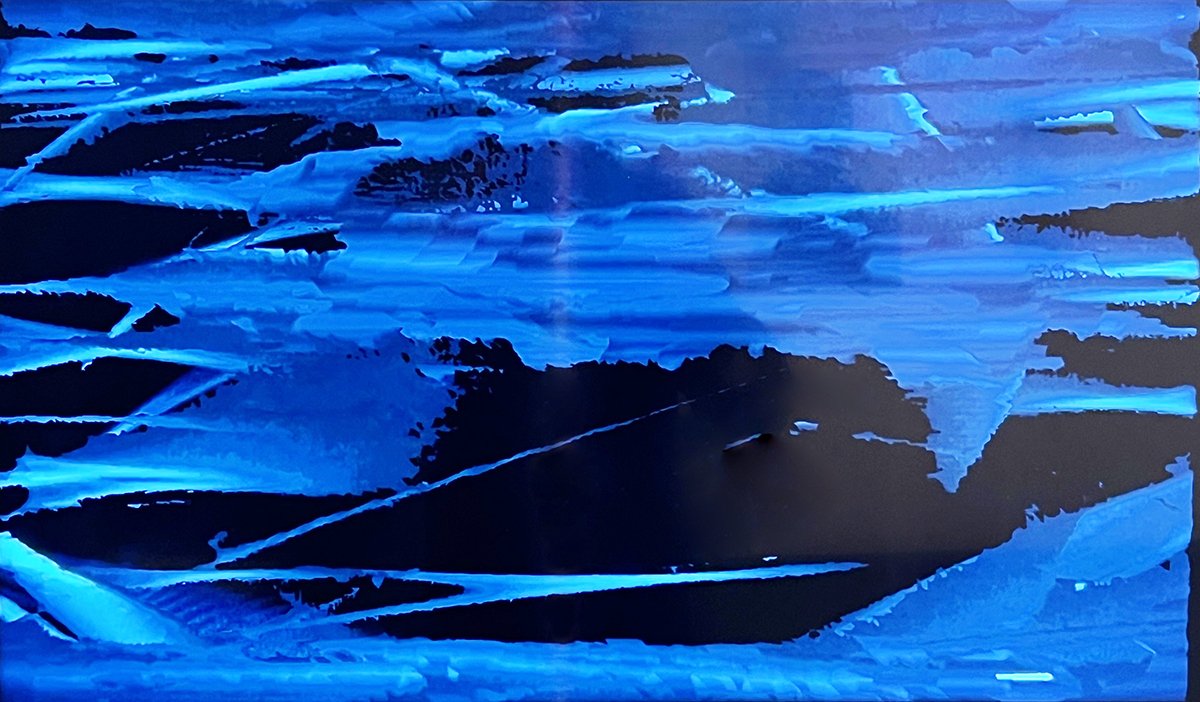

Deborah Bernagozzi, Lodestones (for Stan Ostalj-Kotkowski), 2024, single channel silent color video made with wobbulator, Jones frame buffer, Panasonic MX-50 mixer, Eurorack modules, Signal Culture Modular Apps Input Amp, Frame Buffer, PXLMSH, and video mixer. Image by Stephen Shugart.

Deborah Bernagozzi’s Lodestones (for Stan Ostalj-Kotkowski) is a silent recording of a live performance at the Signal Culture Studio in Loveland. [19] It is a personal and surprisingly emotional ode to an obscure video innovator, Stan Ostalj-Kotkowski. She created this piece for the Intermediale Festival of Audiovisual Forms in Leginica, Poland. [20]

In the late 1950s, as Bernagozzi notes, Ostalj-Kotkowski experimented with magnetism to alter and warp CRT televisions’ electron gun on the screen. Thus, the the term “lodestones” in title of the work is apt, referring to naturally magnetized minerals. For this video performance piece, she uses a “wobbulator” invented by Nam June Paik and Shuya Abe—two groundbreaking collaborators in the early 1970s who used TVs and communication technologies. [21]

An installation view of Visual Reality: Redefining Artistic Experience through Technological Innovation at Artworks Center for Contemporary Art. Image by Stephen Shugart.

Certainly, the paint brush, oil paint, and tools like Van Gogh’s perspective frame were once innovative technologies that offered more options for artists to redefine and speed up the creation and transmission of an aesthetic vision. Visual Reality highlights how the Artworks Center’s artists approach artistic experience while addressing technological innovation. All the while, it is the artists’ hands, feelings, and creativity that control and transform their works into authentic artistic experiences, not simply exercises in using the wow factor of technological innovation for its own sake.

Stephen Shugart (he/him) is a Denver-based light artist, fiction writer, and playwright. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Colorado State University and is a member of Edge Gallery in Lakewood, Colorado.

[1] From Brian Kane’s artist’s statement.

[2] From Susan Stuart’s artist’s statement.

[3] From Sylvia Eichmann’s artist’s statement.

[4] From Ashley Nason’s artist’s statement.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] From SJ Carlisle’s artist’s statement.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] From my conversation with Elizabeth Surinami on 1/11/25 and from Elizabeth Surinani’s artist’s statement.

[12] From Ana Maria Botero’s artist’s statement.

[13] Ibid.

[14] From Augustus Dallabetta’s artist’s statement.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] From Jason Bernagozzi’s artist’s statement.

[18] Ibid.

[19] From Debora Bernagozzi’s artist’s statement. For more information about Signal Culture see signalculture.org/.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid. See also www.medienkunstnetz.de/works/paik-abe-synthesizer/, accessed January 17, 2025.

[22] Ibid.