Ungrafting

Hương Ngô: Ungrafting

Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center

30 West Dale Street, Colorado Springs, CO, 80903

March 1–July 27, 2024

Admission: $5-$10; Members, Students and Teachers with ID, and Kids 12 and Under: free

Review by Nina Peterson

Hương Ngô’s Ungrafting at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center (FAC) focuses on the politics of visibility in the context of French colonial knowledge production in Vietnam. The exhibition examines how power shapes what is seen and what is made to be unseen.

An installation view of Hương Ngô’s exhibition Ungrafting at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. Image courtesy of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College.

Vision and the ability to control and reproduce it through technologies such as photography have long been tools of establishing and expanding colonial empires. Against this colonial visuality, artist Hương Ngô proposes care—practices involving intergenerational collaboration and embodied knowledge communicated by physical touch and sound—as a way of repairing the rifts in our understanding of the past and of honoring people made to disappear by structures of power.

An installation view of Hương Ngô’s exhibition Ungrafting at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College. Image by Nina Peterson.

This first solo exhibition of Ngô’s work in Colorado spans several gallery spaces and includes works on paper, photographs, sculptures, and videos in addition to objects from the FAC’s permanent collection selected by the artist. Curated by Katja Rivera, Curator of Contemporary Art, the exhibition asks how we can contend with the violent history of French colonialism in Vietnam, including in apparently innocuous manifestations such as agricultural science.

An installation view of Hương Ngô’s exhibition Ungrafting. Image by Nina Peterson.

Many of the artworks in the exhibition examine grafting, which was mobilized by the French in colonizing Vietnam during the late-nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries. [1] Grafting is a horticultural technique that involves the splicing together of plants, so they grow into one. For Ngô, this technique stands for the brutality of colonization itself. The artist offers “ungrafting” as a way of working against the harms perpetrated by colonialism. As the wall text in the exhibition explains, Ngô collaborated with translator Hùng Dương to arrive at a Vietnamese translation of the term “ungrafting” (phóng thích cây chủ, literally, “to liberate the host tree”) that carries connotations of political resistance and ecological healing.

The artist Hương Ngô with her work Graphs, 2024, wood, clamps, and sound. Image courtesy of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College.

The practice of ungrafting is poetically realized in the work Graphs (2024), a sculpture made of clamps and tree branches collected by the artist and her son, who assisted in fastening together the boughs and twigs. Headphones mounted on an adjacent wall play audio recordings of the creative process—melancholic creaks and cracks, the sounds of metal tightening on wood. Fine wires suspend the piece from the ceiling and the configuration appears to grow upwards, out of the floor. Made from fallen or broken branches, this piece materializes attentive mending and evokes ghostly echoes—expressions of pain resulting from the violence that caused the need for such repair.

Hương Ngô, Graphs, 2024, wood, clamps, and sound. Image by Nina Peterson.

The sonic spectrality of ungrafting in Graphs signals absences: people and things that escape visual capture but that persist, detectable through other senses. According to the artist’s website, her research-based practice “gives form to individual and collective narratives that might otherwise be lost—inviting the past to haunt the present—sculpting a future within the ruination.” [2]

Hương Ngô, We Are Still Here, 2021, hectographs. Image courtesy of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College.

In the effort to counter absences in historical records, it makes sense that Ngô’s multidisciplinary practice often begins in the archive. One of the key manifestations of imperial knowledge is the archive—a site recognized for its historical authority and neutrality despite all that it intentionally omits. Describing the destructive operation of imperial taxonomy, political theorist Ariella Aïsha Azoulay states, “Everything and everyone must have its precise place in endless lists, indexes, compendiums, and repertoires. Such a place in the archive is meant to supersede people’s place in a world previously shared with others.” [3]

Beyond physical violence, colonialism spreads and strengthens itself by instituting systems based on categorization, acquisition, timelines, and quantification. Such imperial knowledge systems make traditional and Indigenous approaches seem obsolete or obscure them entirely.

Hương Ngô, Latent Images (Grafts), 2024, Van Dyke Brown prints on paper. Image by Nina Peterson.

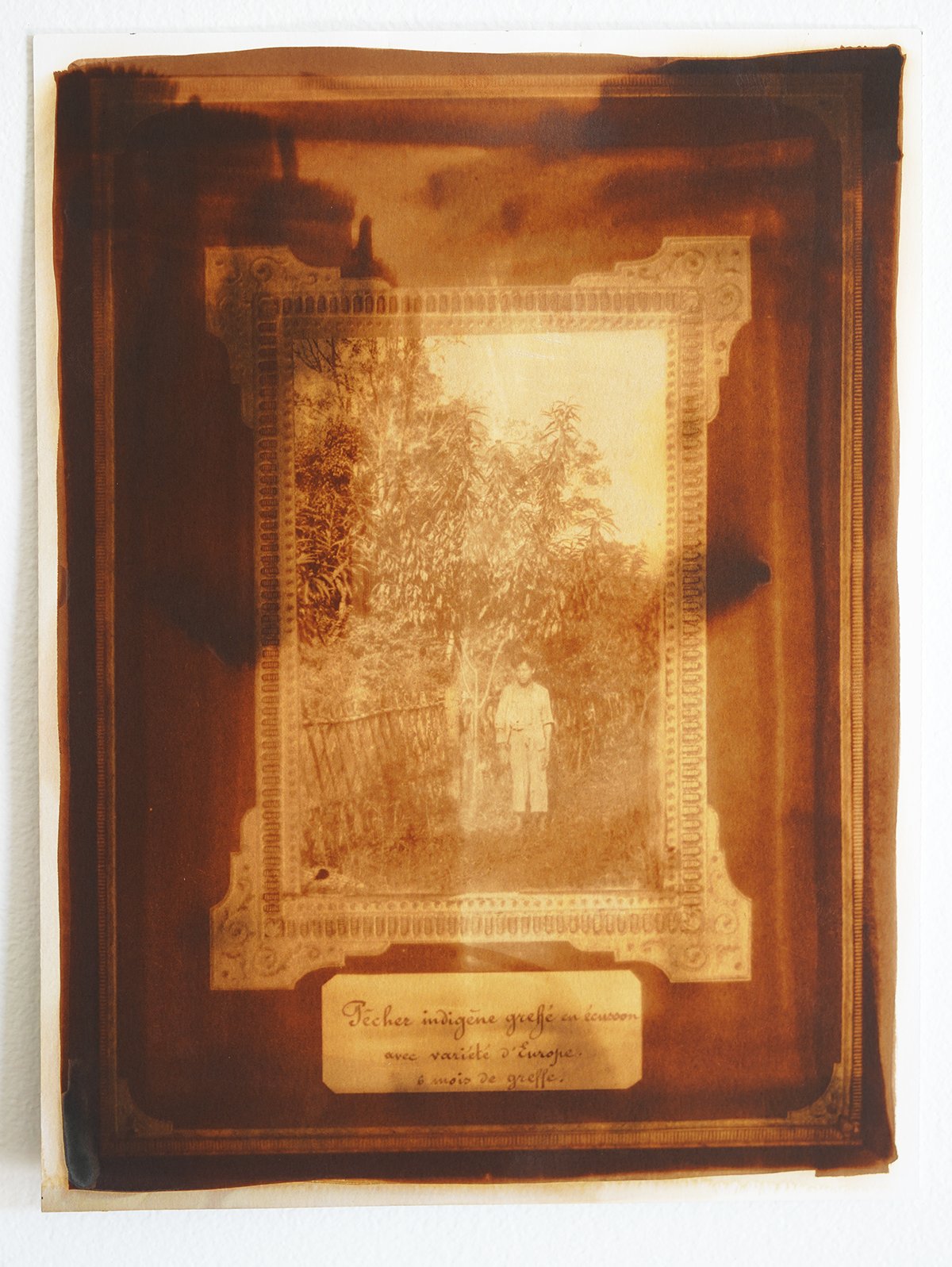

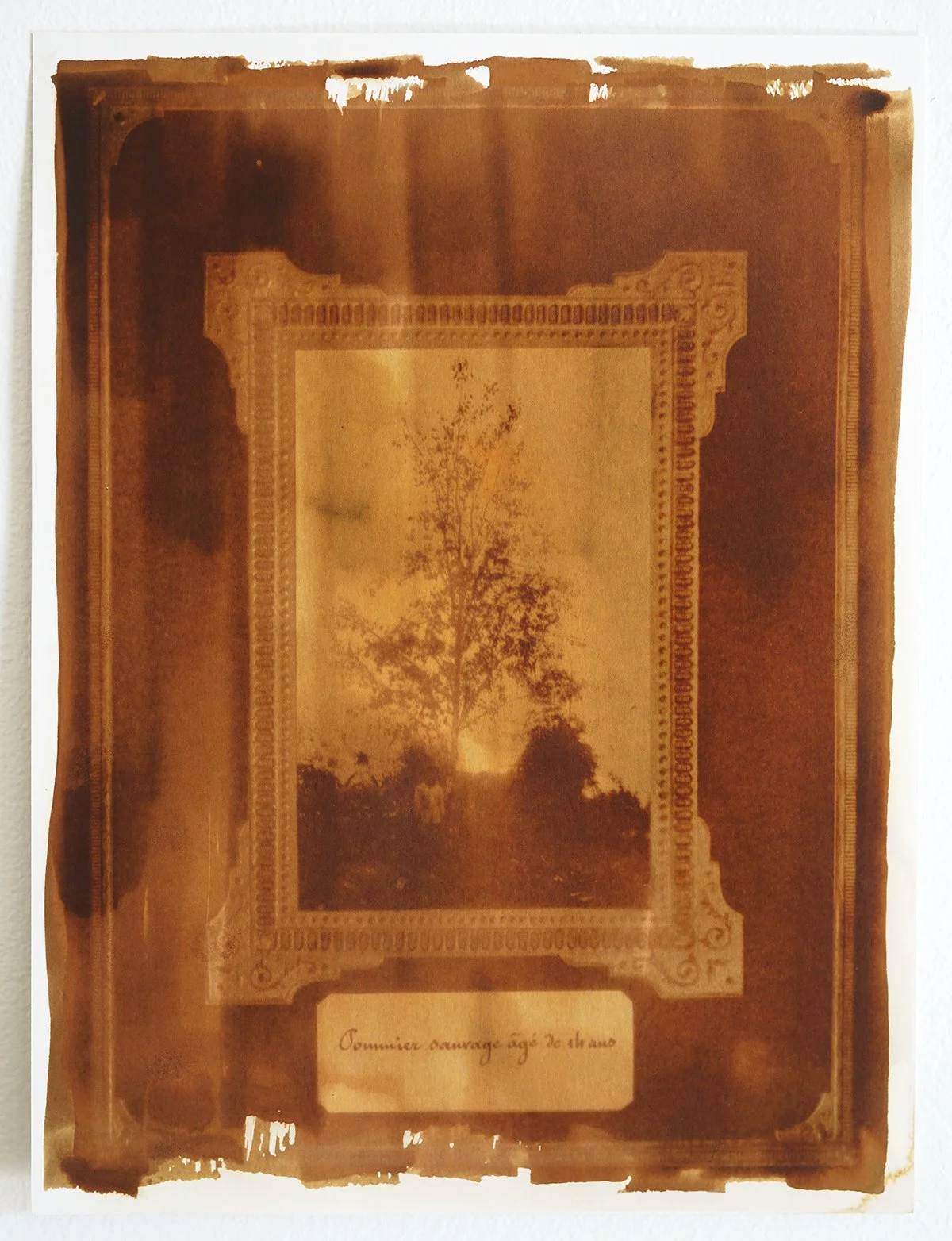

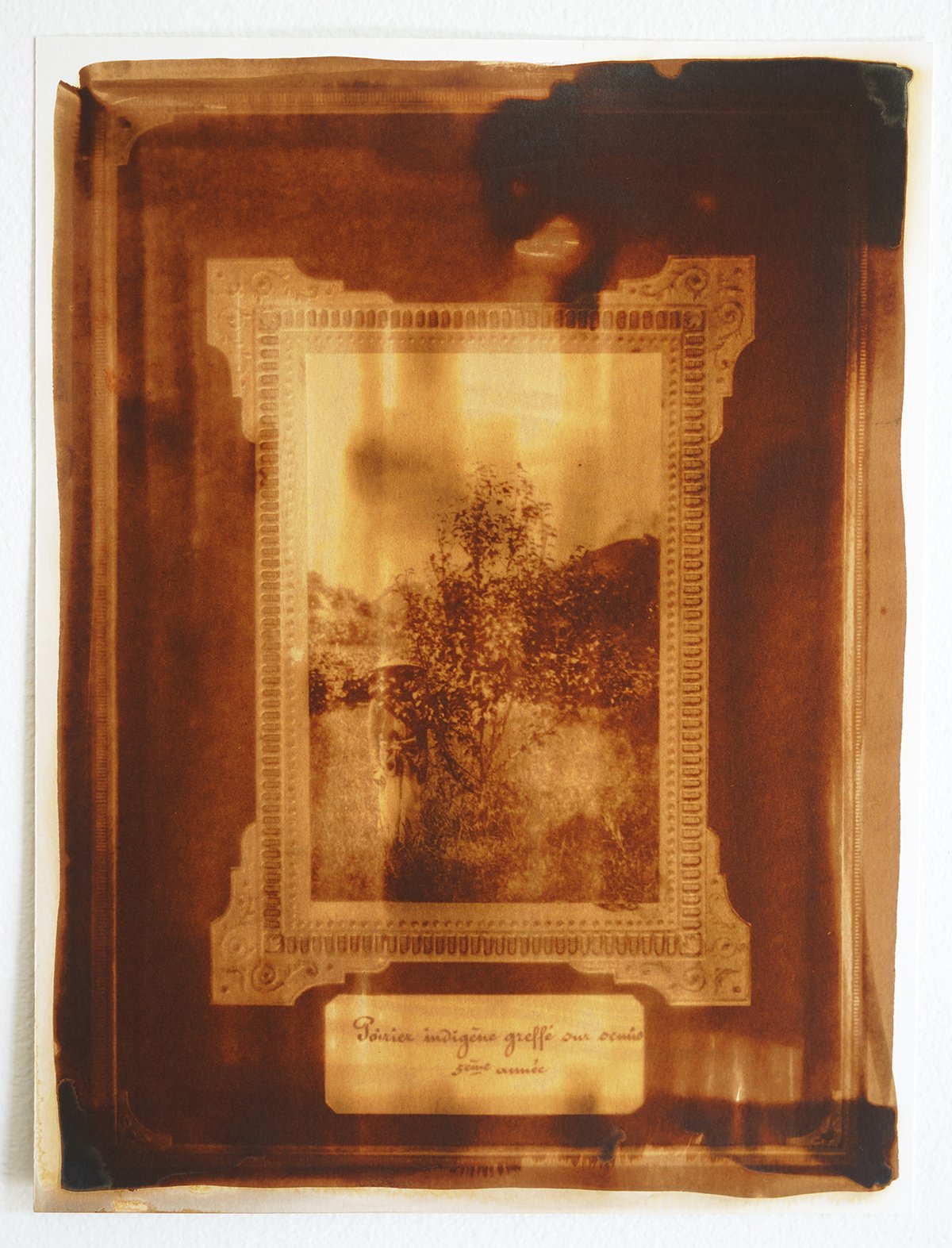

Latent Images (Grafts) (2024) retools archival photographs to challenge imperial mechanisms of dehumanization. Installed in groups on three walls, the series reproduces documents the artist encountered during research in the French national archives in Aix-en-Provence. To make the series, Ngô reprinted early twentieth-century photographs of trees and tree grafts planted in Vietnam by the French colonial empire.

The series shows the institutional framework of the archive. In addition to the photographic images, Ngô’s series depicts the embossed mattes and captions that framed the prints in the archive. This choice draws attention to framing and captioning as strategies of imposing order in the context of political control, what photography theorist John Tagg describes as “the violence of meaning.” [4]

Hương Ngô, Latent Images (Grafts), 2024, Van Dyke Brown prints on paper. Image courtesy of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College.

According to Tagg, a photograph’s “frame” is not just the choices that a photographer makes when deciding what to include and exclude in a camera’s viewfinder and the final image. The photographic frame also refers to larger social and political systems of power, of which photography and the archive are determining factors. For Tagg, framing cuts out important aspects of larger realities even as it claims to depict an objective truth.

Hương Ngô, Latent Images (Grafts), 2024, Van Dyke Brown prints on paper. Image courtesy of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College.

It remains a persistent myth that photographs—especially archival images in state-run institutions dedicated to the keeping of history—are “truthful” in the sense that they show the world the way it is or was, the way it must be. The colonial frame is made explicit in Latent Images (Grafts), reminding viewers of the mechanisms by which photography as a tool of empire claimed and reinforced its own power through a series of techniques made to seem natural or inevitable.

Hương Ngô, Latent Images (Grafts), 2024, Van Dyke Brown prints on paper. Image courtesy of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College.

Exhibition texts explain how Ngô used a historical photographic printing method that was common at the time the original photographs were produced. Van Dyke Brown printing involves making images from a photographic negative, typically made on a glass plate. Using this method involves coating a surface, often paper, in a light-sensitive emulsion, placing the coated paper flat against the negative, and exposing the paper-negative combination to the sun.

Hương Ngô, Latent Images (Grafts), 2024, Van Dyke Brown prints on paper. Image courtesy of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College.

The Van Dyke Brown process uses a silver-iron emulsion, which turns a rich brown color when exposed to ultraviolet light. This printing-out process typically finishes with “fixing”—a step that prevents additional transformation of the image in the light. But Ngô didn’t fix the photographs in Latent Images (Grafts), which is a choice that will result in the eventual darkening and illegibility of the images.

Hương Ngô, Latent Images (Grafts), 2024, Van Dyke Brown prints on paper. Image courtesy of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College.

The details in Ngô's Latent Images (Grafts) point to the materials and work involved in making a subject appear—or disappear—on paper or in the archive. At the edges of some of the Van Dyke Brown prints, between the pictured archival frame and the physical museum frame, white paper meets the sepia tone of the photographic images. Craggy and uneven, this meeting shows Ngô’s application of the silver-iron emulsion.

Hương Ngô, Latent Images (Grafts), 2024, Van Dyke Brown prints on paper. Image courtesy of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College.

In other works in the series, a splotchy metallic sheen appears on the surface. The visual effects look like dripping, soaking, and pooling, and they draw attention to the materiality of photography—the chemicals and minerals used to create the light-sensitive emulsion. These chemicals both make visible a site of colonial violence and veil it, a tension the historian of photography Siobhan Angus notes when asserting that “Paradoxically, the same chemicals that cause harm can document extractive practices and processes, making visible what extractive capitalism renders invisible.” [5] Ngô's process highlights the original purpose and effect of the archive as a tool of colonization that diminished the Vietnamese. The artist then denaturalizes this system of knowledge, showing that it contains within it its own undoing.

Hương Ngô, (Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai letter), 2017, laser-cut onion skin paper on teak backing. Image by Nina Peterson.

Touch—both gestural and emotive—is palpable throughout the exhibition. Ngô’s writing shows the artist’s hand as well as the sorrow that accompanies the work of research in an archive marked by violence and loss. [6] In the works based on archival letters and documents written about, to, and by Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai, Ngô laser cut type-written words into paper made from onion skins. Minh Khai was a co-founder of the New Vietnam Revolutionary Party and pivotal figure in the Vietnamese resistance against the French.

Hương Ngô, (Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai letter), 2017, laser-cut onion skin paper on teak backing. Image by Nina Peterson.

Along with the content from the original letters, Ngô cut into the paper comments she made in the marginalia. Ngô’s annotations include translations about the historical timeline of Minh Khai’s revolutionary actions, highlighting the distinctiveness of handwriting (how each individual has a unique style of mark making) and the strange intimacy of reading archival documents. The laser-cutting process also rendered much of the text illegible, underscoring the tension between visibility and invisibility as strategies of both subversion and oppression.

Hương Ngô, Da/Skin (I, II), 2024, stitched handmade dó paper. Image by Nina Peterson.

I visited the museum with my parents, and my dad noted the museum directives not to touch the artworks that are prominently displayed on stanchions at the entrance to the exhibition. He thought they must be necessary because of the tactility of Da/Skin (I, II). The work consists of dual panels hanging side-by-side. One grouping is a golden ochre hue, the other is a deep bone color.

Hương Ngô, Da/Skin (I, II), 2024, stitched handmade dó paper. Image by Nina Peterson.

To create each panel, the artist stitched together small, rectangular sheets of dó paper in a grid. The surface of individual sheets of paper carries delicate wrinkles and indentations. The stitching is dense, creating thick, protruding ribs connecting the sheets. Rivera’s exhibition essay likens these textural elements to scars and skin, further emphasizing the embodiment central to the tradition of making and sharing this traditional art form. [7]

Hương Ngô, Da/Skin (I, II), 2024, stitched handmade dó paper. Image by Nina Peterson.

The wall text explains that hand making dó paper from tree bark dates to the thirteenth century and is a tradition shared intergenerationally. The work of making the paper—a months-long, multistep process that involves soaking the bark, grinding it into a pulp, creating a slurry, and molding sheets with a frame and bamboo sieve—is a kind of embodied transferal of knowledge from elders to youth. These artworks contain memories of physical creation, inspire desire to touch in the present, and restore Indigenous Vietnamese embodiment and personhood to the imperial archive that sought to eliminate it.

Nina Peterson (she/her) is a PhD candidate in art history at the University of Minnesota. Currently based in Denver, she researches histories of photography, film, and performance in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

[1] Michitake Aso, “The Scientist, the Governor, and the Planter: The Political Economy of Agricultural Knowledge in Indochina During the Creation of a ‘Science of Rubber,’ 1900–1940,” East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal 3, no. 2–3 (2009): 231–56. doi:10.1215/s12280-009-9092-7.

[2] “About,” Hương Ngô’s artist website, www.huongngo.com/.

[3] Azoulay argues that decolonization involves first identifying the way colonialism works to be able to repair its wounds. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (Verso Books, 2019), 173.

[4] Tagg explains how photography acts as a tool of domination. Analyzing the parallel between the language used to describe photography and language used to describe the court and legal proceedings, he asserts that the photographic frame produces its own kind of violence. Tagg articulates the “violence of meaning” associated with photography as “a violence that acts in and across bodies, spaces, and machines that make up the instructive tableau with which we have begun to produce the discursive event, not only by marking it out, pinning it down, or cutting it to size, but, above all, by calling it into place and exposing it, while making sure it stays within the frame.” John Tagg, The Disciplinary Frame: Photographic Truths and the Capture of Meaning (University of Minnesota Press, 2008), XXVI.

[5] In Camera Geologica, Angus historicizes the labor and colonial displacement involved in mining for chemicals used in photographic technologies and describes how the process of extraction abstracts and invisibilizes the labor involved in acquiring materials. Siobhan Angus, Camera Geologica: An Elemental History of Photography (Duke University Press, 2024), 18.

[6] Which isn’t to say that these are the only feelings prompted by doing archival research or communicated by Ngô’s artworks. Triumph, solidarity, and tenderness also run through the research and exhibition.

[7] Katja Rivera, curator’s essay for Hương Ngô: Ungrafting, available at fac.coloradocollege.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Curator-Essay_English.pdf.