Prismatic

Prismatic

Dairy Arts Center

2590 Walnut Street, Boulder, CO 80302

May 12-July 6, 2023

Admission: $5 requested donation

Review by Danielle Cunningham

Prismatic, a new exhibition at the Dairy Arts Center, features queer artists in honor of June’s Pride Month. [1] Curator Drew Austin designed the exhibition as a mirror of its title, with a color spectrum section in the McMahon Gallery and black and white sections in the MacMillan Family Lobby, Polly Addison Gallery, and Hand-Rudy Gallery.

An installation view of the exhibition Prismatic at the Dairy Arts Center in Boulder with Scottie Burgess’s Loaded Logo on the right, 2023, flocking and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 72 inches. Image courtesy of Dairy Arts Center.

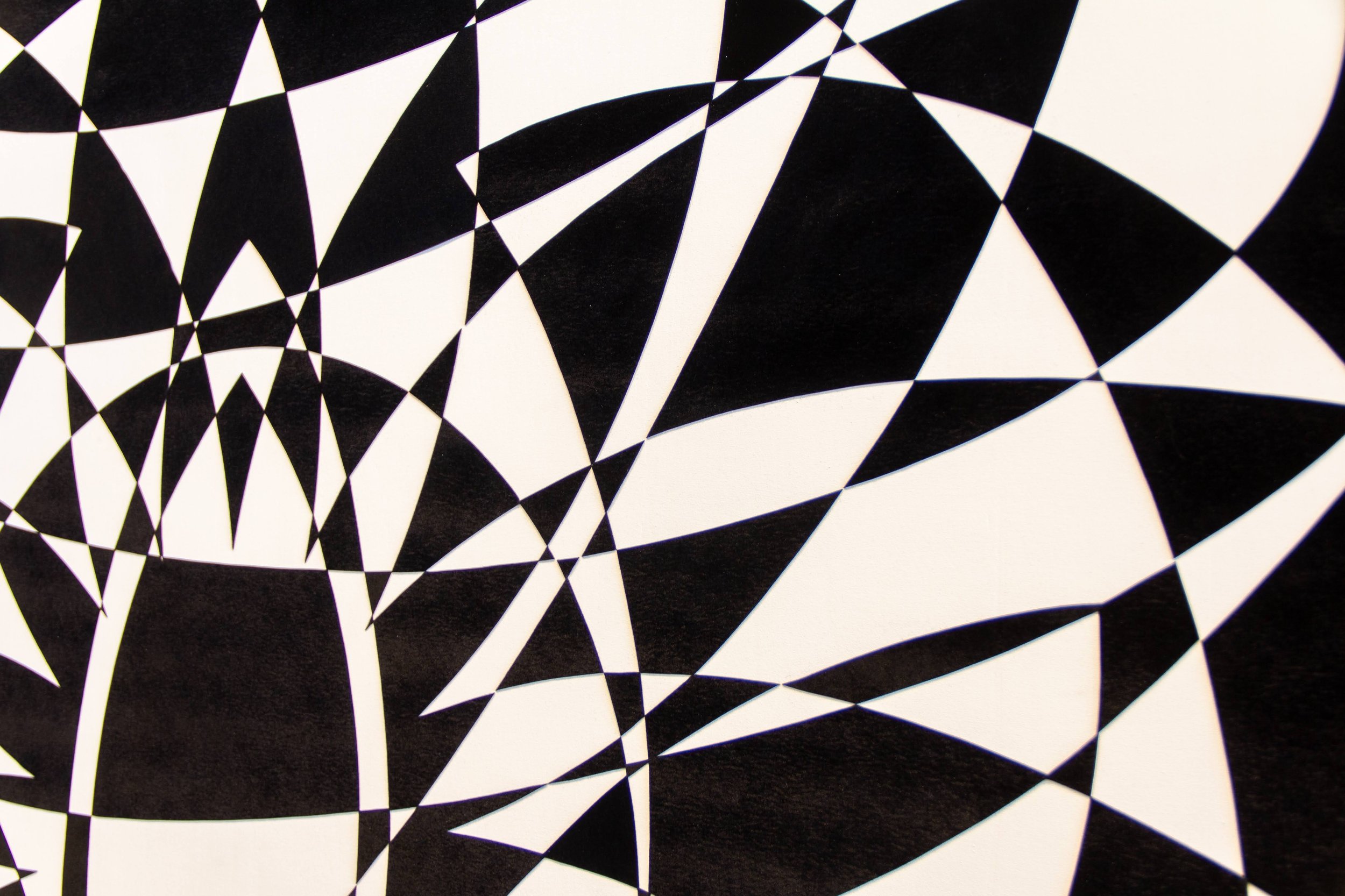

Detail of Scottie Burgess’s Loaded Logo, 2023, flock and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 72 inches. Image courtesy of Dairy Arts Center.

In the black and white section, Scottie Burgess’s Loaded Logo seems to spin and vibrate. The psychedelic lotus flower design on the large circular canvas effectively creates a prismatic portal. The artist has a background in electronic music and the rave industry, to which this work alludes. Burgess expresses his thoughts on contemporary logos, relating them to sigils or symbols used to focus a magick practitioner’s intent, and aligning the cut-up technique used in this work with divination. The artist also references the exhibition theme, calling the prism a tool of visual culture used to “reflect on the influence of contemporary power structures.” [2]

Cherish Marquez, Flux, 2023, animation, 1920 x 1080 pixels, 02:07 minutes. Video still courtesy of the artist.

Cherish Marquez’s animation Flux compounds the floral motif, depicting a dark, flower-like image increasing and decreasing in size as it moves vertically across the mostly white landscape. A white root system reaches out to the flower, generating a sense of longing as the distance between the objects decreases. Ultimately, other shapes enter the frame, gliding across the surface to intersect with one another and epitomize Marquez’s definition of flux as “any effect that appears to pass or travel through a surface or substance.” [3] Like ghosts, these shapes’ outlines are barely visible as they intersect, while a voiceover gives directions to both the viewer and the animation itself. The objects visually narrate their relationship to each other and to space, sometimes silently colliding, sometimes floating by in peaceful co-existence, creating a utopian metaphor for a future Earth.

MaryLou and Agnes, a portrait from Carey Candrian’s series Eye-to-Eye: Portraits of Pride, Strength, Beauty, digital photography. Image courtesy of the artist.

A black and white exhibition wouldn’t be complete without a series of photographic portraits, tenderly rendered here by Carey Candrian. Focusing on queer women ages 59 to 85, Candrian’s Eye to Eye allows the women to speak for themselves. Candrian titles each photograph with the subjects’ names and provides their testimonials, giving insight into their coming out stories, experiences of stigma and discrimination, and the ordinariness of their lives, encouraging viewers to relate to them as everyday people. Because each subject’s story is different, this work illustrates the spectrality of the queer community exceptionally well.

Nathan Hall, You're Not the Boss of Me, 2019, screen printed leather sheet music, leather cord, hardware, music-etched paddles, and tuning fork. Image courtesy of Dairy Arts Center.

San Canessa’s water and ink drawing and Alli Lemon’s graphite and collage works are standouts in the exhibition. Both artists contribute abstraction and gestural mark-making, connecting to each other’s work energetically. Tyler Alpern’s drawing of Nathan Hall and Nathan Hall’s installation based on his own composition for harpsichord work in tandem add unexpected musical references to round out the black and white section.

A view of the exhibition Prismatic at Dairy Arts Center in Boulder. Image Courtesy of Dairy Arts Center.

As part of Austin’s design, the color spectrum section groups similarly-colored works together, accentuated with spotlights of color that hit the walls above. Austin also subtly positions several small prisms in corners high overhead around the gallery. Selected from an open call, artists in this section of the exhibition demonstrate both individuality and shared identity—utilizing a diversity of media while synchronizing within the rainbow.

Hudson Hatfield, Claire, 2022, Aves Apoxie® sculpt, house paint, foam, spray paint, and wood, 60 x 26 x 14.5 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Hudson Hatfield’s two wall-mounted sculptures offer religious connotations with their resemblance to nooks for icons. Prioritizing a central, three-dimensional figure in front of an orange, red, and yellow gradient background, Claire features a headless form wearing what appears to be a dress, though the form’s gender is ambiguous. The figure’s arms are positioned behind its back, casual yet assertive. Much like several saints, the figure levitates. Similar in structure, I Go Both Ways depicts a large open mouth, complete with teeth and protruding tongue. Several white stars graze the tongue’s surface while an organic white stream of unknown liquid hangs off to one side. Ambiguous, comical, and a little irreverent, these works add levity to what can be a heavy exhibition.

Detail of Joel Swanson’s [ s ], 2023, DYMO® label tape on panel, 14 x 11 inches. Image courtesy of Dairy Arts Center.

Joel Swanson’s [ s ] calls attention to the role of the letter “s,” repeatedly punching it onto horizontal layers of plastic label maker tape. The red rectangular work is small and discrete but ingenious in concept and execution, alluding to the sibilant “s” stereotypically attributed to gay men’s speech. Labeled as sibilant because of its similarity to a snake hissing, the sibilant “s” is used as both an identifier within the gay community and a source of stigma for which gay men are often ostracized. By enacting repetition, Swanson enhances the presence of the “s,” marking it as significant although common, notable but not in need of being noticed.

Alexander Richard Wilson, the Darkest, part 4, oil on canvas, 36 x 24 inches. Image courtesy of Dairy Arts Center.

Alexander Richard Wilson’s inky blue painting the Darkest, part 4 appears flat but upon closer inspection, dissolves into numerous textured layers. Their signature impasto brushstrokes form a nighttime or possibly charred landscape. Richard Wilson balances between abstraction and figuration, rejecting the idealized American landscape tradition and leaving the viewer to fill in the gaps, which like identity spectrums, are vast.

Louis Trujillo, A Great Blow, 2019, colored pencil on paper, 11 x 22 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Contrasting with Richard Wilson’s murky, intellectual imagery, Louis Trujillo’s four colored pencil self-portraits are light and playful. These works depict Trujillo, a drag performer, in various stages of drag. In A Great Blow, he wears a long wig, showing off bedazzled fake fingernails, while in Rugged and Rhinestoned, he presents a salt-and-pepper beard. In Lace, the artist wears red lacy underwear and black and red stilettos and in Leather, black lace-up underwear and sneakers. Trujillo speaks to his personal experience on the gender spectrum, which includes being bullied for his femininity by both gay and hetero-male communities.

A view of pink and purple works in Prismatic at Dairy Arts Center in Boulder. Image courtesy of Dairy Arts Center.

Talent from Colorado and beyond shines in Prismatic, as does the breadth of the queer artist community. More than that though, this exhibition illustrates that art doesn’t occur in a vacuum. Life experiences lead to ideas and influence artistic styles, generating concepts to which the public can relate. Maybe minds won’t be made more inclusive or accepting by this exhibition—as it seems largely tailored to a queer or an already-receptive audience—but minds will certainly be strengthened in the idea that there is no such thing as identity, singular. One identity can’t be separated from another as humans are hybrid beings, capable of occupying many spaces at once.

Danielle Cunningham (she/her) is an artist, scholar, and independent curator. She writes about science fiction, gender, sexuality, and disability, with an emphasis on mental illness. The co-founder of chant cooperative, an artist co-op, she holds a master’s degree in Art History and Museum Studies from the University of Denver.

[1] Featured artists include: Tyler Alpern, Finley Baker, Shaunie Berry, Scottie Burgess, Carey Candrian, San Canessa, Dagny Chika, Sarah Darlene, JUHB, Jesse Egner, Levi Fischer, Kate Geman, Nathan Hall, Hudson Hatfield, Sophie Hill, Grace Hoag, Kora Hope, Padyn Humble, Talia Johns, Alli Lemon, Cherish Marquez, Robert Martin, Dez Merworth, Nems, Zachariah Rampulla, Alexander Richard Wilson, Tracy Stegall, Joel Swanson, Louis Trujillo, and Chloe Wilwerding.

[2] From the artist’s statement.

[3] From the artist’s statement.