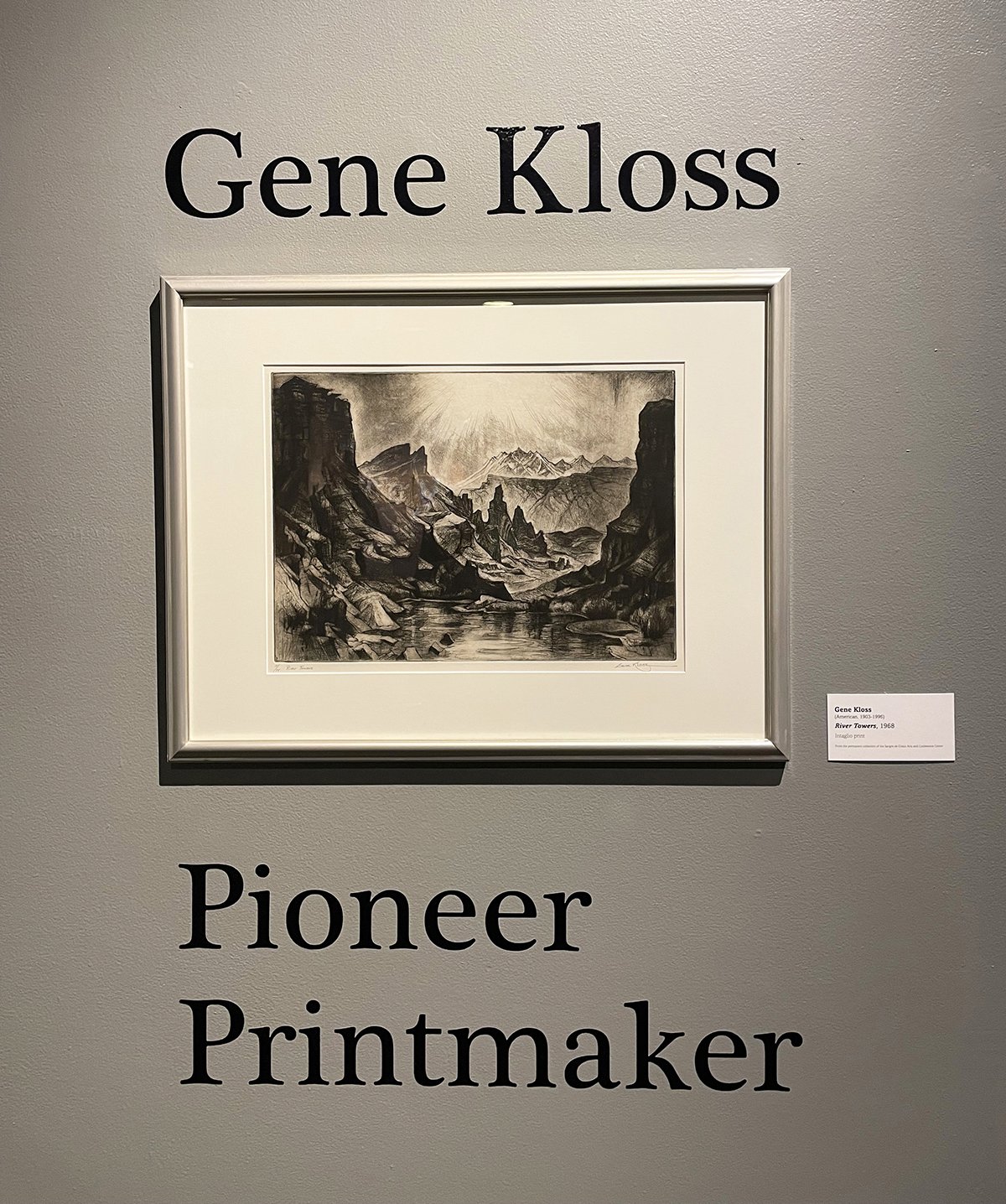

Pioneer Printmaker

Gene Kloss: Pioneer Printmaker

Sangre de Cristo Arts & Conference Center

210 N. Santa Fe Avenue, Pueblo, CO 81003

November 19, 2022-May 13, 2023

Admission: Adults: $10; Children, Seniors, and Military: $8; Members: Free

Review by Genevieve Waller

Over the course of many years, the Sangre de Cristo Arts & Conference Center in Pueblo has amassed hundreds of drawings, paintings, and prints by the American artist Gene Kloss. A selection of these works from the artist’s nearly 70-year artistic career are now on view in the Arts Center through May 23. While Kloss is mostly known for her depictions of New Mexican landscapes and Native peoples and cultures, the exhibition contends that what is most remarkable about her work is her skill and innovation as a printmaker, no matter the subject. Yet the relationship between artist and subject always matter, and the questions that Kloss’s themes raise about representation may be the most intriguing aspects of the show.

An installation view of the exhibition Gene Kloss: Pioneer Printmaker at the Sangre de Cristo Arts & Conference Center in Pueblo, Colorado. Image by DARIA.

Kloss was born Alice Geneva Glasier in Oakland, California in 1903. She received a degree in art from the University of California at Berkeley in 1924, where she first used a printing press and learned to etch. When she married in 1925, she took her husband Phillips Kloss’s last name but also changed her first name to the gender-neutral Gene—a strategic move to avoid discrimination as a woman in the art world. The year 1925 also marked the beginning of many trips to northern New Mexico, where she and her husband lived part-time thereafter and more or less permanently from 1953 onward.

A wall of black and white prints in the exhibition Gene Kloss: Pioneer Printmaker at the Sangre de Cristo Arts & Conference Center. Image by DARIA.

The Arts Center’s collection consists primarily of examples of Kloss’s black and white etchings, which comprise the bulk of their holdings and dominate the exhibition. A few of the artist’s drawings and paintings supplement the show and attest to Kloss’s draftsmanship and breadth, and give insights into her process and intention.

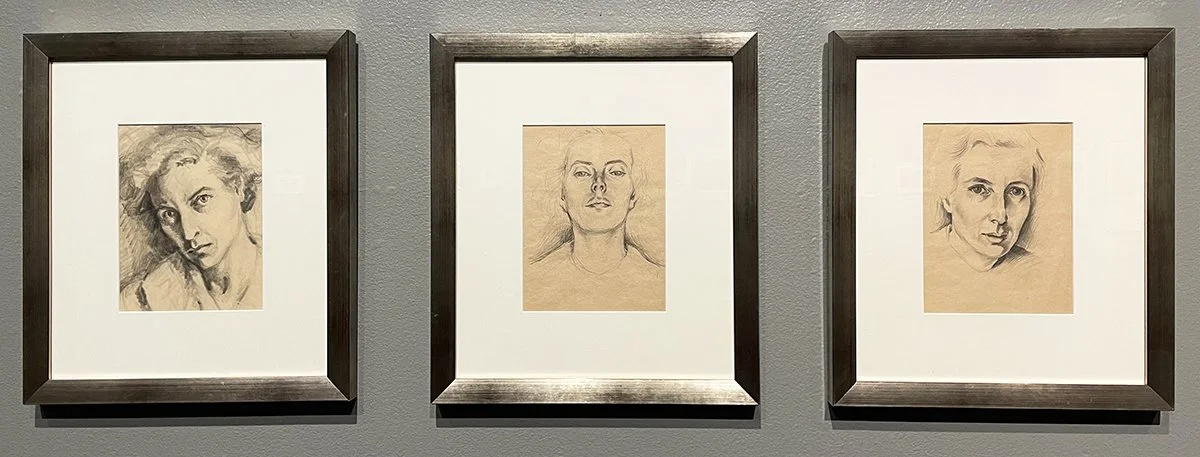

Gene Kloss, Sketches and Studies, dates unknown, charcoal and pencil on paper. Image by DARIA.

Three untitled self-portrait pencil and charcoal sketches hung together portray the artist confidently staring back at the viewer. Focusing primarily on her face, Kloss depicts herself from three different angles and emotional states. On the left, we see her face in a three-quarter view, gazing seriously as the strong lines of her arched eyebrows, the part of her lips, and flared nostrils impart a sense of judgment. In the center, she looks down her nose with chin raised; despite her youthful features and her hair in light wisps around her face, her expression asserts her power. On the right, Kloss’s stare is softer and sad, with more delicate shading and a still penetrating gaze.

Gene Kloss, Self Portrait with Golden Gate, 1951, intaglio print, 13.5 × 10.75 inches. Image by DARIA.

Kloss’s intaglio Self Portrait and the Golden Gate from 1951 shows a similarly confident look back at the viewer. [1] She depicts herself drawing, declaring her role as an artist, and hints at her origins by including the San Francisco Bay and Golden Gate Bridge in the window behind her. Viewed in concert, this print and the drawings argue for her seriousness as an artist through both her self-assurance and her demonstration of technical skill.

Gene Kloss, The Guitar Player, 1934, intaglio print, 7.25 x 5 inches. Image by DARIA.

Yet Kloss represents the male figure in an intaglio print from 1934 in contrast to her assertive self-portraits. The Guitar Player shows its subject looking down at his guitar frets, despite being positioned in the same way as Kloss's intaglio self-portrait. Looking closely, the brows, cheekbones, and curves of both the player and the artist are quite alike, but the former is demure as an object to ogle. Complicating matters is a description of The Guitar Player from Kloss's catalog raisonné, which notes that "The model [for the guitar player] was a neighbor in Cañon, New Mexico." [2]

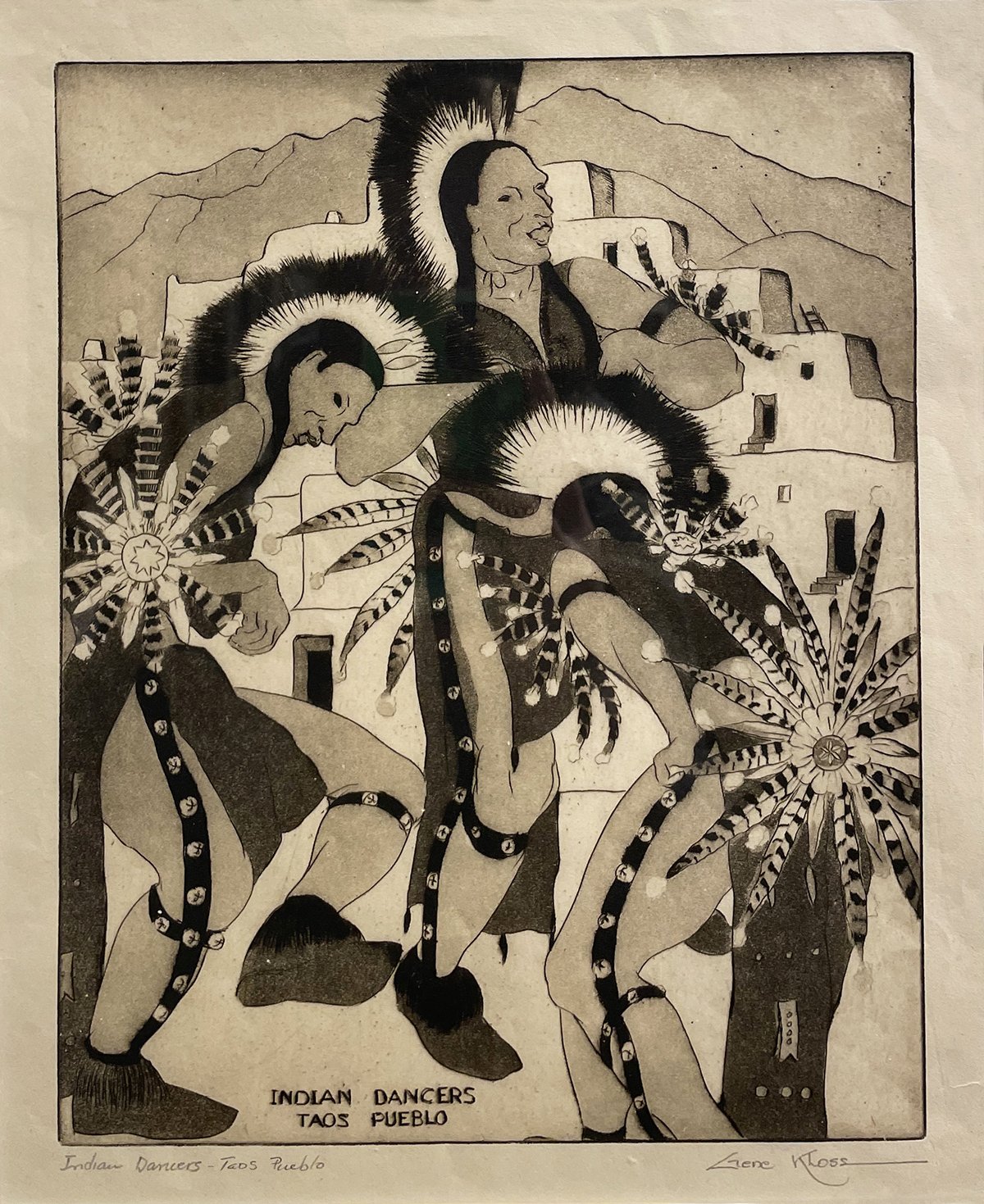

Gene Kloss, Indian Dancers–Taos Pueblo, 1932, intaglio print, 9.875 x 7.875 inches. Image by DARIA.

Questions of agency become more complex when we turn to Kloss’s extensive images of Native people. Indian Dancers–Taos Pueblo from 1932 portrays three men in regalia and headdresses dancing in front of a complex of adobe structures with mountains in the far background. The politics of Kloss’s gaze as a white artist depicting Indigenous men is impossible to ignore from our current standpoint, and the manner in which she renders the men’s faces with black ovals for eyes, single curving lines for facial contours, and tinted skin with no hatching or shading is markedly different from her powerful self-portraits or sensitive guitar player.

The story behind this work further problematizes Kloss's choice in subjects, since “The models were Gene and Phillips’ friends Adam Trujillo and his two sons, Jim and Pat. This print may have served as an advertising poster for Adam Trujillo’s dance troupe.” [3] If the dancers were Kloss’s friends, and they even commissioned this work, how do we interpret the artist’s choices of representation?

The title wall of the exhibition Gene Kloss: Pioneer Printmaker at the Sangre de Cristo Arts & Conference Center, with Kloss’s River Towers, 1968, intaglio print. Image by DARIA.

The title of the exhibition, Pioneer Printmaker, adds another layer of complexity. In the context of American history, the word “pioneer” is fraught and considered synonymous with “colonizer.” While European settlers building homesteads in North America is our history, it is also the history of the forcible genocide and displacement of Native people and innumerable acts of violence against them. It is impossible to use the word “pioneer” without invoking this meaning, particularly in an exhibition that includes portrayals of Native people, their homes, and the land they have inhabited for thousands of years.

Gene Kloss, Winter Woods, 1941, intaglio print, 6.75 x 8.4 inches. Image by DARIA.

“Pioneer” also takes on a different aspect when we consider works like Winter Woods (1941). The image of New Mexico in winter, featuring expressive trees with undulating limbs and contrasting white snow, is also proof that Kloss explored what were once solely Native lands. While we admire the loveliness and skill of these and other landscape renderings in the exhibition, we must remember the histories that made them possible and their implications.

Representation matters in multiple senses, and Kloss’s drawings, paintings, and prints relay messages of power, show the meetings of cultures, and demonstrate how depictions are never neutral. We can engage with the Kloss’s works on many levels, including admiring her technical skill, her struggle to be taken seriously as a woman in the art world, and the range of subjects she portrayed, but we must also contend with how her images render people and places from a “pioneer” perspective.

Genevieve Waller (she/her) is an artist and writer originally from Wichita, Kansas. She has a BA in Art History, an MFA in Photography and Art History, and an MA in Visual and Cultural Studies. She is also a long-time college radio DJ, most recently on Radio 1190 in Boulder.

[1] Kloss created this print for the required portrait submission when she was elected to the National Academy of Design as an Associate Member. See “Biographical Sketch: You Are Going To Be An Etcher” by Dory Hulburt in A. Eugene Sanchez, ed., Gene Kloss: An American Printmaker, A Raisonné, Vol. I (Taos, New Mexico: De Teves Publishing, 2009), pp. 2-3.

[2] Sanchez, Gene Kloss, Vol. I, p. 129.

[3] Sanchez, Gene Kloss, Vol. I, p. 102. Also of note: “The print ‘Taos Devil Dance’ was done after the dance was held in Marie and Adam Trujillo’s home in Taos Pueblo. Gene and Phil Kloss were in attendance. Later Adam went to the Kloss home and helped Gene get the costuming right. When the print was finished, Adam said ‘Yes, that is the way it looks at our house that night.’” Sanchez, Gene Kloss, Vol. I, p. xv.