Lay of the LAND: Interpretations of SCAPES

Lay of the LAND: Interpretations of SCAPES

Madden Museum of Art

6363 S. Fiddler’s Green Circle, Greenwood Village, CO 80111

September 9, 2024–June 27, 2025

Admission: free

Review by Madeleine Boyson

It’s one of the first things you learn in an art history course: landscape doesn’t place very high in the Western hierarchy of genres. From the Renaissance to the nineteenth century, royal academies across Europe rigorously ranked paintings based on subject, skill, ingenuity, and virtue. Preeminent history painting and its kin—mythology, allegory, and religious “high styles”—were praised for embodying imagination and morality. Portraiture and scenes of everyday life ranked second and third, while animal paintings and still lifes were relegated to last place. But lost in the middle was landscape, a difficult genre in which to find success, at least until the early 1800s. [1]

An installation view of Lay of the LAND: Interpretations of SCAPES at Madden Museum of Art with the front desk in the foreground. Image courtesy of the Madden Museum of Art.

While these rankings ought not matter in our postmodern world, viewers can’t help but categorize art into similar genres today. Contemporary artists still paint portraits, everyday scenes, and still lifes. And now in Lay of the LAND: Interpretations of SCAPES, on view at Madden Museum of Art through June 27, 2025, student curators from the University of Denver question and praise that other foundation—landscape—illustrating that it is less a distinct artistic genre than it is a sum of all the others.

Chen Chi, Redwoods, 1968, watercolor on paper, 82.5 x 46.2 inches. Image courtesy of the Madden Museum of Art.

Lay of the LAND was cultivated (but not realized) in 2019 by eleven curatorial practicum students under the tutelage of former Madden Museum director Nicole Parks, who consulted on installation this year. [2] Students were involved in each stage of project management, from conceptualization to writing wall texts. This learning opportunity is foundational to the exhibition, according to acting supervisor and Vicki Myhren Gallery director Geoffrey Shamos. The resulting show is “a seasoned dish with many cooks,” he says, even if some of the flavors are surprising.

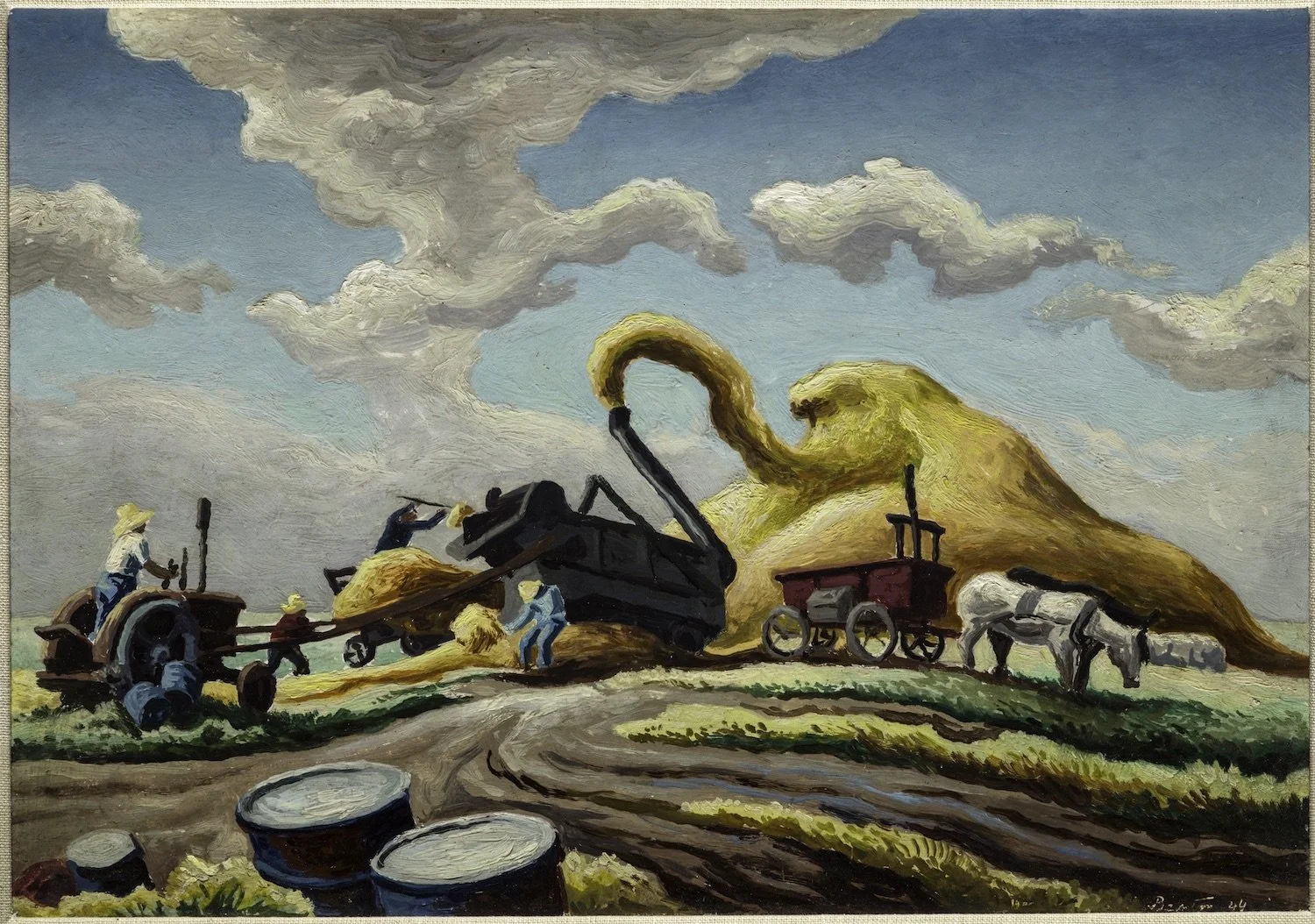

Top to bottom: Thomas Hart Benton, Missouri Spring (Study for Spring on the Missouri), 1938, acrylic on panel, 15.75 x 17.9 x 1.9 inches; Thomas Hart Benton, Rice Threshing, 1944, oil and tempera on Masonite board, 18 x 22 x 2.5 inches. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Since the early nineteenth century, landscapes in the Western mind have variously shifted into and out of an aura of the amateur, often overlooked as the purview of seaside hobbyists or Painting I & II classes. It’s not that critics consider landscapes to be bad, per se, but that we frequently don’t consider them at all. What Lay of the LAND contributes is not only a consideration of this genre, but a new way of seeing it. Add in new curators who aren’t yet jaded about the art world, and the results are refreshing.

Top left: Ando Hiroshige, The Temple Kiyomizu, 1951, woodcut, 13.5 x 18 inches. Bottom left: Ando Hiroshige, The Cherry Blossoms of Arashiyama, 1951, woodcut, 13.5 x 18 inches. Right: J.M.W. Turner, Destruction of Both Houses of Parliament, 1835, watercolor on paper, 15 x 17 inches. Image courtesy of the Madden Museum of Art.

Thomas Moran, Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came, 1859, oil on canvas, 30 x 44.5 inches. Image courtesy of the Madden Museum of Art.

The museum’s airy dove gray gallery shows works from the Madden Collection and DU’s larger University Art Collections at the Hampden Art Study Center grouped into themes. “Tracing Traditions,” references genre conventions in various cultures, for instance through woodcuts by Utagawa (Andō Tokutarō) Hiroshige and a watercolor by J.M.W. Turner next to more classical North American scenes like Thomas Moran’s Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came (1859).

An installation view of Lay of the LAND: Interpretations of SCAPES. Top left to right: Erik Brunetti, Camo, 1997, paint on wood skateboard deck; Andy Warhol, Camouflage, 1987, screen print, 38 x 38 inches; Plinio Nomellini, Figura nel Bosco (Girl in Forest), 1910, oil on canvas, 47 x 58.9 inches; Chen Chi, Redwoods, 1968, watercolor on paper, 82.5 x 46.2 inches. Image courtesy of the Madden Museum of Art.

“Altered Scapes” considers emotional interpretations of the genre as in Erik Brunetti’s painted skateboard Camo (1997) next to Plinio Nomellini’s Figura nel Bosco (Girl in Forest) (1910), a vibrant cacophony of impressionistic light and foliage enveloping the title figure. Elsewhere, the curators celebrate nature’s variable humors in “Sensational Seasons,” as in George William Sotter’s Evening (circa 1928) of a farm under snow.

Wilson Hurley, Black Mesa, 2000, oil on board, 47.5 x 47.5 inches. Image courtesy of the Madden Museum of Art.

“Land Marks” reflects on our human relationship with nature by forging city and land together in scapes, and “Form and Perspectives” sees balance as a determining factor in a scene’s mood. The oil Black Mesa (2000) by Wilson Hurley takes this scale to the extreme, laying a mesa to rest beneath a fluorescent orange sky in a luminous, twilit tableau. Lay of the LAND showcases an incredible scope of styles, subjects, cultures, and media which, in sum, upends those old, arbitrary hierarchies that relegate landscape to idealized, soulless, or predominantly European horizons.

Albert Bierstadt, Mountain Landscape, date unidentified, oil on paper board. Image courtesy of the Madden Museum of Art.

Left to right: Mel Strawn, Ghost Cars, 1965, oil on canvas. Hung Liu, Mountain Ghost, about 2014, mixed medium, 96 x 96 inches. Image courtesy of the Madden Museum of Art.

Yet more fascinating is the way these works prompt conversation across themes and around the room. It’s refreshing to see Albert Bierstadt’s small but mighty Mountain Landscape (date unidentified) by the front desk, with its craggy peak looming over a valley, in the same exhibition as Hung Liu’s perilous mixed media Mountain Ghost (about 2014). The latter combines calligraphy with metamorphosed foxes over more craggy peaks, a tiger, and a woman all in flat perspective, dripping with unease and painting medium.

Gregory Mirow for Steuben Glass Works, Spreading Pines, 1973, etched glass. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Daniel Sprick, Studio with View of the City, 2012, oil on board, 29.5 x 35.2 inches. Image courtesy of the Madden Museum of Art.

Elsewhere, Gregory Mirow’s icy etched glass Spreading Pines (1973) echoes Daniel Sprick’s austere and spectral Studio with View of the City (2012), while both contrast the dreamy swirls of Thomas Hart Benton’s Rice Threshing (1944). Madden’s curved walls reveal not that these works have themes in common, but that they bring out new views of each other.

Guy Pène du Bois, Crossroads, date unidentified, oil on canvas, 47 x 31 inches. Image courtesy of the Madden Museum of Art.

Before my visit to Madden Museum of Art in September, I would not have categorized Guy Pène Du Bois’ Crossroads (date unidentified) or the gorgeous, abstracted forest in Redwoods (1968) by Chen Chi in the same breath, but am haunted equally by both. Some works are obvious inclusions in a landscape show. Others, like a trio of gelatin silver prints by Lee Balterman, Andy Warhol, and Georgy Zelma of the urban skylines and streets next to Red Army Soldiers resting during the siege of Stalingrad, require more reflection. I’m grateful to see all of them in this show.

Top left: Lee Balterman, Chicago, 1960s, gelatin silver print, 7.4 x 9.5 inches. Bottom left: Andy Warhol, Intersection, May 3, 1982, 1982, gelatin silver print. Right: Georgy Zelma, Untitled (Red Soldiers During the Siege of Stalingrad), 1942, gelatin silver print, 13.25 x 19.3 inches. Image courtesy of the Madden Museum of Art.

And without support from curatorial interpretations of individual works, viewers must decide what constitutes a “landscape” for themselves. Art lovers would therefore do well to trek southward to Fiddler’s Green for a chance to see Lay of the LAND, if only to be reminded that any classification is as expansive or as arbitrary as we make it.

Madeleine Boyson (she/her) is a Denver-based writer, poet, and artist. She holds a BA in art history and history from the University of Denver and makes her living as a communications and editorial coordinator and arts writer.

[1] A prize for “historical landscape” paintings was awarded starting in 1817 and the Barbizon School advanced plein air observations of the French countryside in the 1830s. Dita Amory, “The Barbizon School: French Painters of Nature,” Laura Auricchio, “The Transformation of Landscape Painting in France.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bfpn/hd_bfpn.htm and www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/lafr/hd_lafr.htm.

[2] The curators are Kit Bernal, Miyo Fukuzawa, Megan Gannon, Celia Haims, Marianne Hughes, Karissa Johnson, Savannah Kirksey, Eden Leal, Courtney Lindly, Annie Petty, and Danielle Reisman.

[3] Félibien was a consulting scholar for the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture. Linda Walsh, A Guide to Eighteenth-Century Art (Wiley, 2017), 56.