Entanglements

Entanglements

Center for Visual Art, Metropolitan State University of Denver

965 Santa Fe Drive, Denver, CO 80204

January 13-March 25, 2023

Curated by Cecily Cullen and Natascha Seidneck

Admission: Free

Review by J. Benjamin Burney

Art has an entangled relationship with nature. As the philosopher Aristotle famously said, “Art not only imitates nature, but also completes its deficiencies.” [1] This ancient ideal is critiqued and expounded upon in Entanglements, a new exhibition at Metropolitan State University’s Center for Visual Art. As a lens-based exhibition featuring eleven artists, the show explores our connections to the natural world by illustrating the complex relationships humans have with nature and its resources. These works question humanity’s role in the natural world as caretakers, observers, and even destroyers.

The title wall for the exhibition Entanglements at the Center for Visual Art in Denver. Image by J. Benjamin Burney.

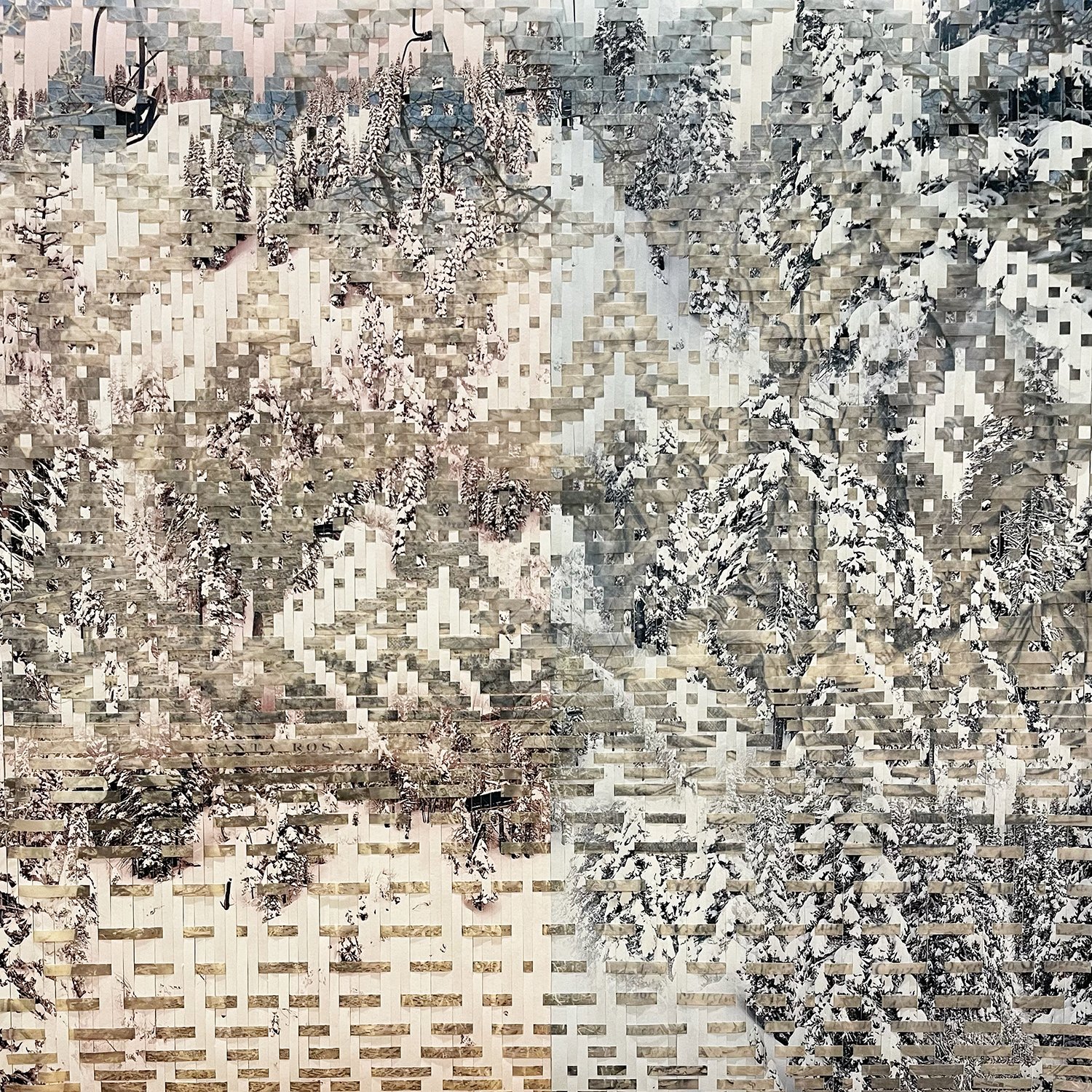

Sarah Sense, Extermination of the American Bison from the Power Lines series, 2022, woven archival inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper and Hahnemuhle rice paper, beeswax, and artist tape. Image courtesy of Center for Visual Art, Metropolitan State University of Denver.

A common theme that flows through Entanglements is the role of the camera in capturing, documenting, or exploiting the natural world, from the microscopic to the macroscopic. In a series called Power Lines, Sarah Sense uses imagery from the British Library’s collection of maps, rare books, and manuscripts along with landscape photography to create collages that explore the intersection between the oppressed and the oppressor. The repurposed images are woven in a traditional indigenous basket-weaving style of the Chitimacha and Choctaw to represent the effects of colonization in North America and to reclaim space for Indigenous cultures.

Sarah Sense, Louisiana from the Power Lines series, 2022, woven archival inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper and Hahnemuhle rice paper, beeswax, and artist tape. Image courtesy of Center for Visual Art, Metropolitan State University of Denver.

Sense exquisitely expresses her identity as the daughter of a Native mother and a non-Native father through a style of photo-weaving that slowly unveils the artwork to the eye. At first, one sees only an ashen mountain landscape in Sense’s work. But upon further inspection, the details hidden in the layers of the collage become apparent. lmages of ski lifts, newspaper articles, and Indigenous iconography speak to the controversial history of settler-colonial relationships.

An installation view of works by Felicity Hammond in the Entanglements exhibition. Image by J. Benjamin Burney.

Felicity Hammond, Hidden Gems, 2022, c-type print, frame, and vinyl hazard tape. Image courtesy of Center for Visual Art, Metropolitan State University of Denver.

In Hidden Gems, Felicity Hammond also creates photographic collages that “blend images of mined landscapes, minerals, power, and (hidden) labor to interrogate resource-based industries.” [2] Hammond employs the complementary colors of orange and blue to produce a gripping contrast that both cautions and intrigues. The artist’s collages place us in the perspective of a viewer staring through a corporation’s windows onto a construction site where torn fences cage the amalgamated stacks of precious resources.

Felicity Hammond, Deep Disposal, 2022, c-type print, wood, and paint. Image courtesy of Center for Visual Art, Metropolitan State University of Denver.

One feels a sense of isolation while also being surrounded by the luxuries and edifices of capitalism, which idealizes the natural world while in the same breath destroying it. Hammond’s work questions our enthusiasm for nuclear energy after using up all non-renewable resources and demonstrates the pivotal moment when humanity moves from extraction to depositing potentially harmful materials into the earth.

An installation view of Jana Hartmann, DIE TÜR INS MEER (THE DOOR INTO THE SEA), 2017–ongoing, photography. Image courtesy of Center for Visual Art, Metropolitan State University of Denver.

Jana Hartmann utilizes photography to illuminate humanity’s obsession with images of nature. In DIE TÜR INS MEER (THE DOOR INTO THE SEA), the artist explores the relationship between various life-sized depictions of scenes of nature in urban settings. These include landscapes painted on the sides of recreational vehicles, jungles graffitied onto brick walls, and large vinyl stickers of ocean vistas in cubicles.

One of the photographs in Jana Hartmann’s series DIE TÜR INS MEER (THE DOOR INTO THE SEA), 2017–ongoing. Image by J. Benjamin Burney.

Hartmann’s juxtaposition of fabricated nature and real nature calls our attention to the incessant appropriation of the natural world and the roles that art and the camera play in this voyeuristic relationship. The work makes us ask: do humans enjoy actual nature, or do we prefer an idealized and anthropomorphized version that is more tamed and suited to our modern proclivities? Have we simulated nature to the point it has become sequestered only to the canvases of concrete civilization?

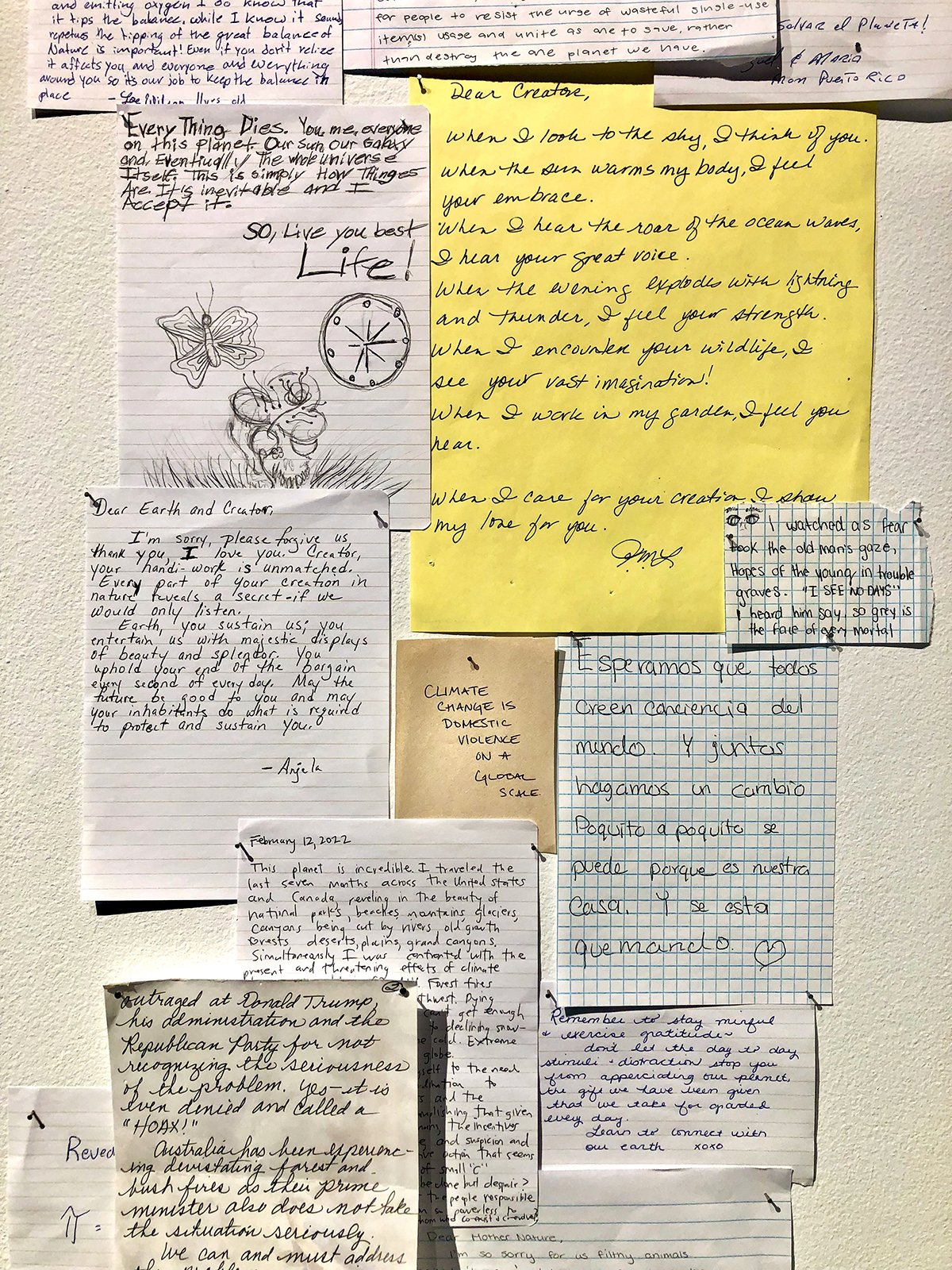

An installation view of Regan Rosburg, dear future, 2020, video, 5:11 minutes and Everything is Fine, 2017–present, handwritten letters, ongoing project. Image courtesy of Center for Visual Art, Metropolitan State University of Denver.

It is in this moment of reflection when we are faced with the extinction of our natural world that the art of Regan Rosburg rings a sounding bell. In her mixed media work dear future, viewers are presented with a video of melting ice caps juxtaposed with a wall of handwritten letters from a diverse group of scientists, community leaders, students, and children expressing their thoughts on the future.

A still image from Regan Rosburg’s dear future, 2020, video, 5:11 minutes. Image courtesy of Center for Visual Art, Metropolitan State University of Denver.

Reading the letters, one feels a cathartic letter being composed in our own hearts for the people of the world who wish to avert a disastrous end for humanity. This is only amplified by watching Rosburg’s video with headphones and hearing the letter writers’ voices played over the beautiful scenic photography of the deteriorating glaciers.

A detail view of Regan Rosburg’s Everything is Fine, 2017–present, handwritten letters, ongoing project. Image by J. Benjamin Burney.

The voices are both hopeful and fearful for what is to come. Quotes like, “Comfort is why we won’t change; humans just want more and more…” are accompanied by children speaking of a world they hope to grow up in. The viewer feels at one moment hopeless and at the next most purposeful, which fits the message that Rosburg tries to convey in her work, saying, “Artists are a crucial voice in discussing climate change and human impact.” [3]

Through Entanglements, the viewer is confronted with the hypocrisies of modernity and the idealism with which we treat nature. Seeds are planted before our eyes and are embedded deep in our hearts. The artists gently pull back the layers upon which we have built our civilization. They ask us if there is an alternative future where we do not commodify nature, roping it off only for tourism and Instagram photo opportunities. Instead, they posit a world of caretaking, coexistence, and balance where the natural world and humans are unified in an entangled harmony.

J. Benjamin Burney (he/his) is an MFA & MBA candidate at the University of Colorado in Boulder. He specializes in creating immersive installations using performance and mixed media works. He is the Creative Director of Zoid Art Haus, a design house based in Denver, Colorado that uses storytelling to create experiences, products, and services geared toward making a more inclusive, equitable, and empathetic society.

[1] Aristotle, Aristotle’s Poetics, New York: Hill and Wang, 1961.

[2] From Felicity Hammond’s wall text.

[3] From Regan Rosburg’s wall text.