Colorado Grasslands Interpreted Through Textiles

Handweavers Guild of Boulder: Colorado Grasslands Interpreted Through Textiles

NoBo Bus Stop Gallery

4895 Broadway, Boulder, CO 80304

January 5-26, 2025

Admission: Free

Review by Felicity Wong

“This we know. / The earth does not belong to us, / we belong to the earth.” I encounter these words in Chief Seattle’s (Duwamish/Suquamish Tribe) poem, quoted in Jane Patrick’s artist statement for her embroidered piece, Death Comes to the Prairie. Patrick is one among dozens of artists in the Handweavers Guild of Boulder exhibiting in Colorado Grasslands Interpreted Through Textiles at the NoBo (North Boulder) Art District’s Bus Stop Gallery.

An installation view of the Handweavers Guild of Boulder’s exhibition Colorado Grasslands Interpreted Through Textiles at the NoBo Bus Stop Gallery. Image courtesy of NoBo.

The exhibition features responses to the anthropogenic threats that the Colorado and nearby grasslands continuously face. In 2019, for example, approximately 2.6 million acres of grassland in the northern Great Plains, home to species of ferret, bison, and birds not found anywhere else, were plowed up to make space for row-crop production. [1] Colorado Grasslands reckons with the death of American grasslands through the material resourcefulness central to the textile arts practices on display, allowing viewers to reflect on the relationship between human populations and the natural ecosystems we inhabit.

A view of by the Handweavers Guild of Boulder in their exhibition Colorado Grasslands Interpreted Through Textiles at the NoBo Bus Stop Gallery. Image courtesy of NoBo.

Since 1964, the Handweavers Guild of Boulder has been dedicated to promoting the art of handweaving, and the labor of the individual hand is certainly visible in the intricate stitching, eclectic material juxtapositions, and imaginative detail throughout the show. The exhibition’s accompanying artist statements also contain personal narratives that situate these creations within daily life. In these texts, the makers recount the magical moments that inspired their work, from childhood family road trips, cross-country moves, and time spent gardening, hiking, and looking.

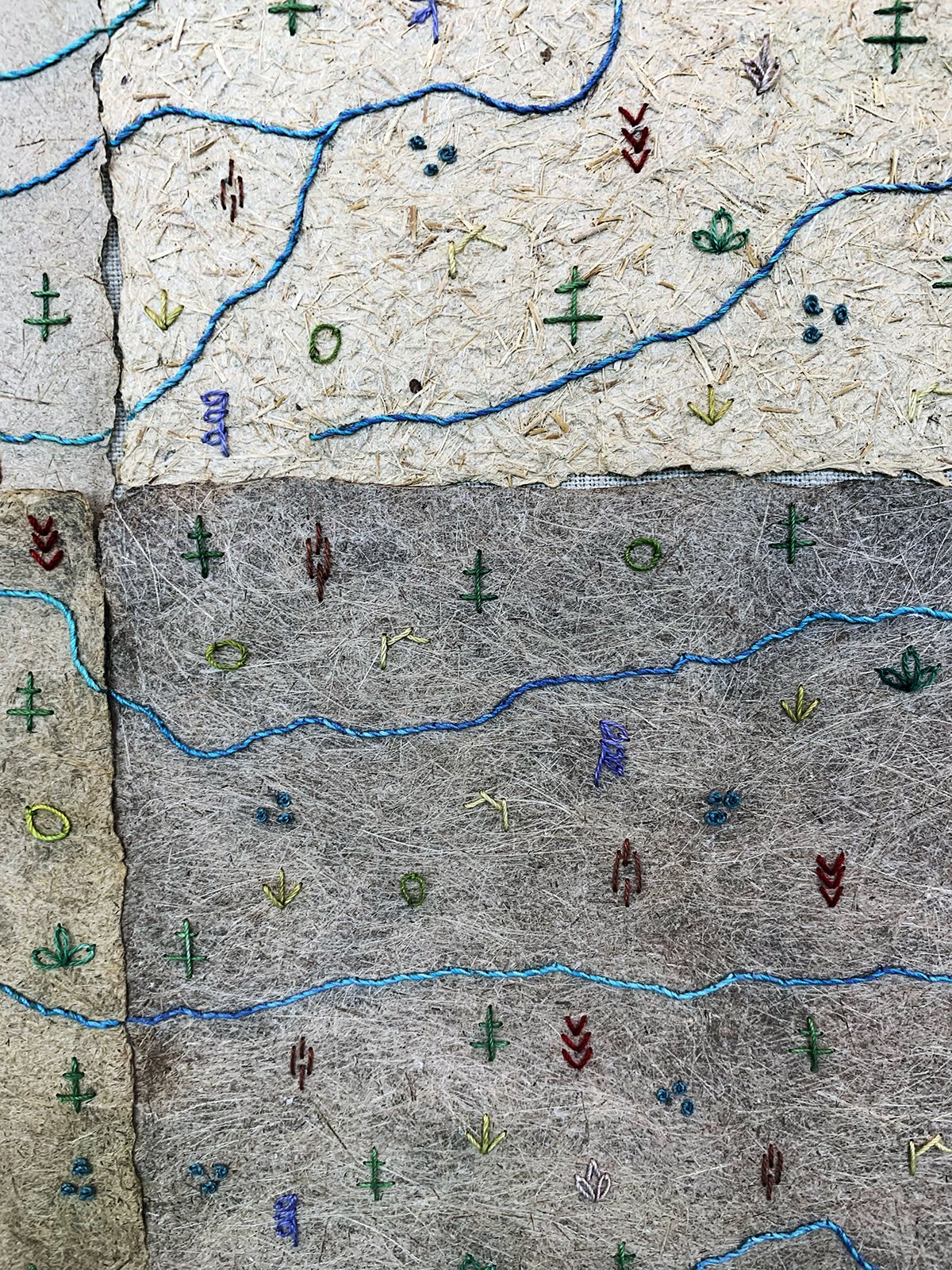

Janet Strickler, Deep Roots, handmade paper made from native plants, hand-dyed vintage and secondhand thread, secondhand fabric, and frame. Image by Felicity Wong.

Janet Strickler, plant species key for Deep Roots. Image by Felicity Wong.

Various brown and beige square paper patches form Janet Strickler’s Deep Roots—a map of the plant ecosystems indigenous to Boulder County. Its every component, from the frame to the fabric, is made entirely by hand, either of vintage, second-hand materials or native plants. Thin threads swarm the surface of the paper, the blue representing the streams and rivers in the county, and the orange outlining six of what Strickler calls “Life Zones” or habitats with distinct plant communities. [2] Hundreds of stitched symbols lie between these threads, each with a different color and arrangement of arrows, dots, and lines. A key to the right of the map lists all the native plant species represented by these symbols.

Janet Strickler, close-up of Deep Roots, handmade paper made from native plants, hand-dyed vintage and secondhand thread, secondhand fabric, and frame. Image by Felicity Wong.

The straight grid lines that frame the map reference the cartographic system imposed by 18th-century European settlers on Indigenous land, contrasting heavily against the melodic chaos of threads and symbols. What landscapes thrived before forces of colonization and industrialism? What has been lost and stolen in the search for newness? What dies when we attempt to sustain more life? These questions haunt the remainder of the show.

Jane A. McAtee, Green is the Color of Grasslands, shibori weaving on an 8 shaft loom, white cotton, thread, and dye. Image by Felicity Wong.

Jane McAtee pays homage to the vivacity of the plants and animals across the Colorado grasslands through Green is the Color of Grasslands. Two textiles hang from wooden sticks on the wall: the left features multi-colored flowers, and the right depicts two bison, a moose, and a bird soaring through the air. A plethora of greens fill the background of both, the subtleties of the light and dark shades swimming into each other. McAtee uses Japanese shibori weaving, which involves throwing picks of thread in the weft to fashion tight pleats that are then dyed, removed, and embroidered, to create this effect.

Karen Krause, Hat, hand knit and hand spun bison and cashmere from a 4-H group in the Fort Collins area. Image by Felicity Wong.

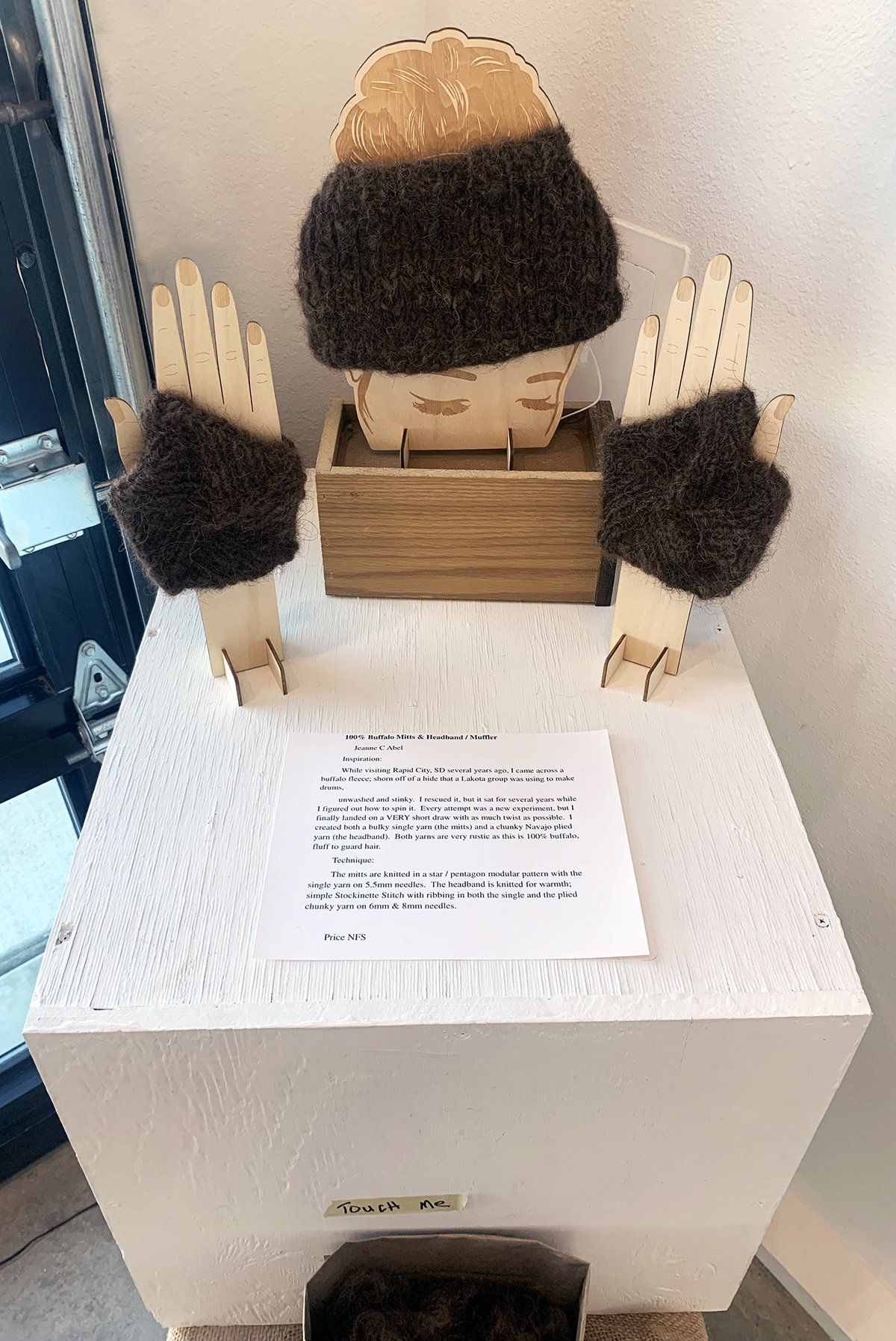

Bison also play a central role in Karen Krause’s Hat and Jeanne Abel’s 100% Buffalo Mitts & Headband / Muffler. The sartorial nature of these works elevate the meaning of resourcefulness. Notably, the process of hand-spinning bison fiber into these articles of clothing presented challenges for the artists.

Jeanne C. Abel, 100% Buffalo Mitts & Headband / Muffler, bison fiber. Image by Felicity Wong.

Abel writes that “every attempt was a new experiment, but I finally landed on a VERY short draw with as much twist as possible.” [3] When Krause began knitting, she did not have enough bison fiber for a hat, so she improvised by combining it with a small ball of cashmere. Krause and Abel’s solutions thus speak to a resourceful sensibility evident in both their material and technique.

Linda Olsson, front of Grasses on the Hill, fabrics, digital photo manipulation, inkjet printing, and embroidery. Image by Felicity Wong.

Linda Olsson, back of Grasses on the Hill, fabrics, digital photo manipulation, inkjet printing, and embroidery. Image courtesy of NoBo.

Clothes appear again in the show—that is, once I look up at Linda Olsson’s Grasses on the Hill. Six pieces of fabric connected by string dangle in the air, each piece slowly spinning like a planet. Denim jean back pockets decorated with embroidered animals, buttons, lace, and fabric are sewn into one side, while cyanotypes of dandelions, branches, and trees are printed on the other. While Krause and Abel recycle bison fiber into clothing, Olsson recycles clothing itself by marrying denim fragments to images of nature in a blue new world.

Lena Kahn, Seas of Tranquility, merino wool, fabric, viscose, silk, alpaca, yarn, embroidery thread, Swarovski crystals, interfacing, and aspen branch. Image by Felicity Wong.

Seas of Tranquility feels especially poignant, viscerally transporting me to the grasslands, with studded stars and a blazing red moon in the stark indigo sky, an abandoned house filled with a darkness reinforced by the delicate twinkling threads surrounding the windows, and trees, living and dying, that punctuate the open prairie. With a blend of organic and synthetic mediums, including Merino sheep and alpaca wool, viscose, silk, and Swarovski crystals, Lena Kahn’s painting tells a story about the coexistences and simultaneities that the grasslands have to offer.

Amy Oien, Prairie Dog Coterie, free-motion machine embroidery and appliqué, and hand-dyed canvas, silk, hemp, and burlap. Image by Felicity Wong.

Amy Oien, close-up of Prairie Dog Coterie, free-motion machine embroidery and appliqué, and hand-dyed canvas, silk, hemp, and burlap. Image by Felicity Wong.

Amy Oien’s Prairie Dog Coterie and Patrick’s Death Comes to the Prairie are positioned but a few images apart on the wall, yet they convey the entirety of a life cycle. Oien leans into a diverse color palette of purples, greens, browns, and blues to illustrate the prairie dog’s underground coterie—a social system that designates each dog with a specific function. The prairie dogs, a keystone species of the grasslands ecosystem, are human-like—stretching, kissing, and conversing. Whether Oien intends to analogize us to the prairie dog, the broader ecosystem to the coterie, or both, her creatures inside and outside the tunnels express a sense of interconnectedness that undergirds the beauty of the grasslands.

Jane Patrick, Death Comes to the Prairie, cotton embroidery floss on cotton fabric. Image by Felicity Wong.

Jane Patrick’s Death Comes to the Prairie is a compact embroidered square, inside which black birds ominously hover around the Nebraska Sandhills—a rainbow of endangered species living among the prairie. The grasslands, which have been immortalized by the exhibition so far in wefts and warps, are slowly dying, stitch by stitch. Toward the end of his poem, Chief Seattle describes the coterie that renders us both perpetrators and victims of this violent fate: “Whatever befalls the earth, / befalls the sons and daughters of the earth. / We did not weave the web of life, / we are merely a strand in it.”

Top: Sue Torfins, Glorious Grasslands, needle felted wool; Bottom: Rozie Vajda, Rippling Moonlit Marsh.

After the 2021 Marshall Fire in Boulder County, the most destructive in Coloradan history, efforts to preserve the state’s grasslands and species have increased. [4] These renewed vows of care have led us to reevaluate our quest for efficiency and abundance. Handweaving, a time-consuming and bodily activity predicated on the reuse of materials given to us by the earth, reveals an alternative truth to the hierarchical construction of humans above nature: that we exist as a part of a larger web of life that cannot be escaped through domination. This exhibition reminds us of the very line between agency and ownership that makes all the difference.

“Whatever we do to the web, / we do to ourselves.”

Felicity Wong’s (she/her) research and writing focuses on contemporary fiber arts, everyday objects associated with Asia and its diasporas, and the relationship between fashion, decay, and language. She received her BA in English from the University of Notre Dame, and currently studies contemporary Art History at the University of Colorado Boulder.

[1] From the Handweavers Guild in Colorado as quoted in the exhibition’s introductory text.

[2] From Janet Strickler as quoted in her artist statement.

[3] From Jeanne Abel as quoted in her artist statement.

[4] From The Watershed Center, “Grasslands Management in Boulder County,” August 11, 2023, https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/62435c5cd6554d4d8143dd0c967fc2d3.