at the line

Ronny Quevedo: at the line

Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College

30 West Dale Street, Colorado Springs, CO, 80903

October 1-December 5, 2021

Curated by Katja Rivera

Admission: Members: Free, Non-Members: $10

Review by Mary Grace Bernard

The show currently on view in the Central and South El Pomar Galleries at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center is Ronny Quevedo’s solo exhibition at the line. It includes works on paper and muslin, as well as a site-specific installation. As the Curator of Contemporary Art Katja Rivera explains in an accompanying pamphlet, the exhibition is a celebration of Quevedo’s recent artistic practice. His works weave together layered histories from across the Americas, speak to the formation of diasporic identities, and use materials and processes connected with immigration both past and present. [1] As a result, Quevedo blurs geographic, historical, and temporal boundaries to highlight the complex narratives of the movement(s) associated with historically marginalized peoples. Before the exhibition opened, I had the pleasure of meeting Quevedo and Rivera and viewing the galleries during installation.

Quevedo (b. 1981 in Guayaquil, Ecuador) is a contemporary Latinx artist living and working in the Bronx, New York. He holds an MFA from the Yale School of Art (2013) and a BFA from The Cooper Union (2003). He has exhibited across the U.S. and has had numerous solo exhibitions. According to art historian Ananda Cohen-Aponte, his works reference Andean and Mesoamerican cultures, soccer fields, gymnasium floors, the Mesoamerican ballgame, and the artist’s personal migration story from Ecuador to the Bronx. [2] Within his body of work, it is the concept of movement that ties sports and play to migration and survival.

Consistent with previous exhibitions of Quevedo’s works, at the line presents art that abstracts movement through time and space in its materials, processes, and compositions. To highlight the effects of colonialism and community displacement on the immigrant working-class in the Americas, the artist uses unconventional materials such as dressmaker’s pattern paper, shoelaces, milk crates, wax, enamel, contact paper, gold and silver leaf, drywall, vinyl, and gesso. Through a subversion of this mix of “high” and “working-class” materials, the artist elevates common household items to monumentalize them. [3] As such, most of the artist’s works in the exhibition extend beyond the realm of traditional painting and drawing.

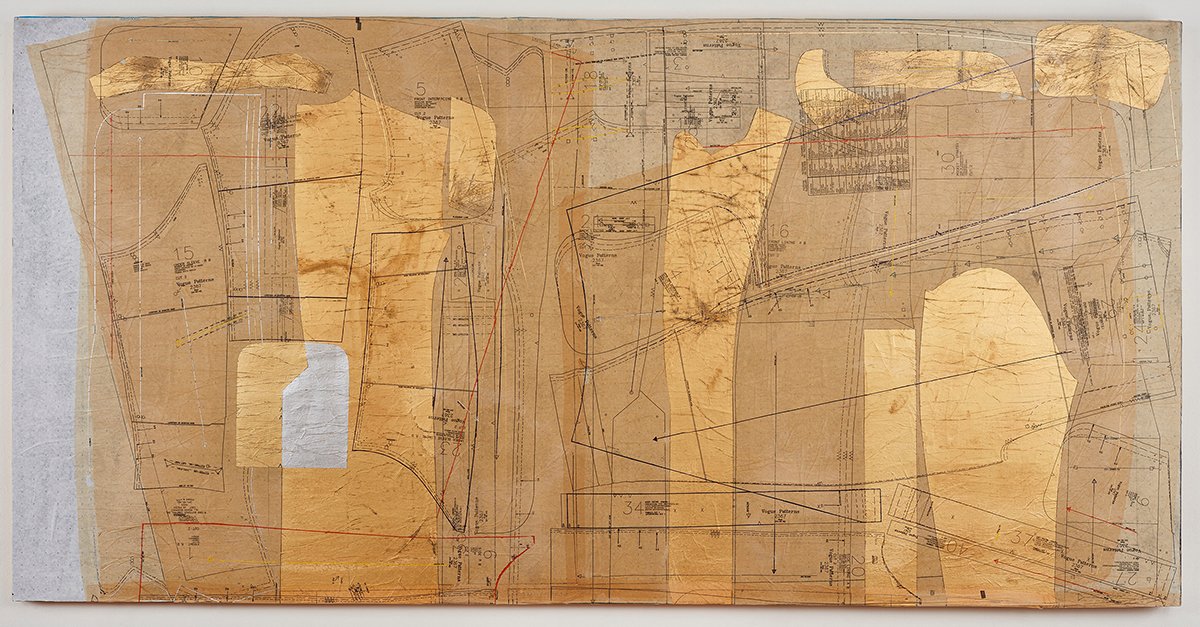

Ronny Quevedo, Zoot Suit Riot at Qoricancha, 2017, pattern paper, enamel, gold leaf, and silver leaf on panel. Image courtesy the artist.

A detail image of Ronny Quevedo, Zoot Suit Riot at Qoricancha, 2017, pattern paper, enamel, gold leaf, and silver leaf on panel. Image by DARIA.

Quevedo depicts a blurring of time and space via dismembered bodies—as is the case with Zoot Suit Riot at Qoricancha (2017)—and fractured geographical spaces—such as revolutions abound (Estadio Olímpico Atahualpa) (2019)—to suggest notions of displacement and the fusion of past and present histories. For Zoot Suit Riot at Qoricancha, in particular, the artist collages and abstracts a zoot suit—a 1940’s symbol for men of color in the U.S. claiming public and political space—using a jacket’s pattern paper parts, and the title also makes reference to the Incan temple Qoricancha (c.1200) in Cusco, Peru. [4] When looking closely at this work, we notice a sleeve here and a breast panel there by following the numbers, directions, and dotted lines of each panel to slowly rejoin each disassembled part back together. To elevate the paper’s material importance and to blur time and space further, Quevedo overlays gold and silver leaf on chosen areas to simulate the pattern’s reflections. As a combined whole, the artwork and its title imply a complicated history of broken spaces and lost time due to disjointed movement and immigration across borders. [5]

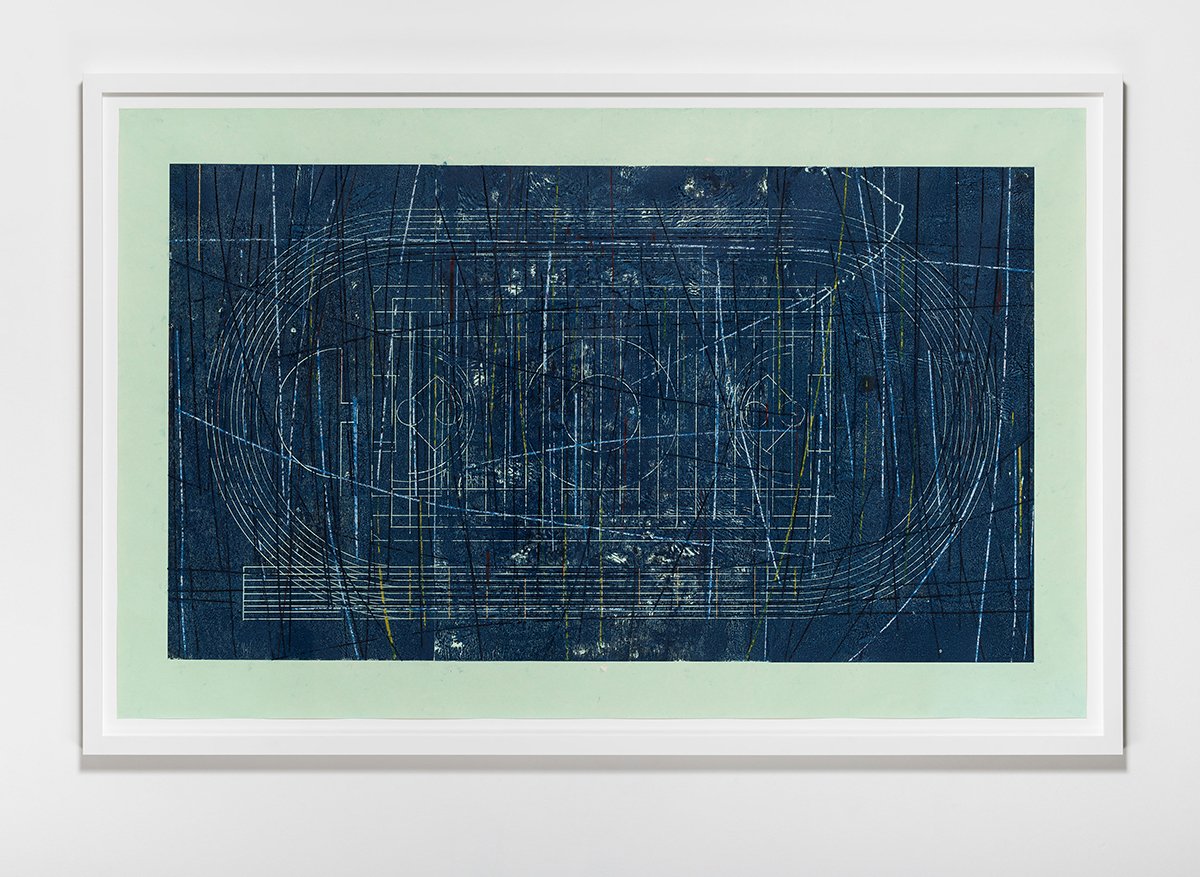

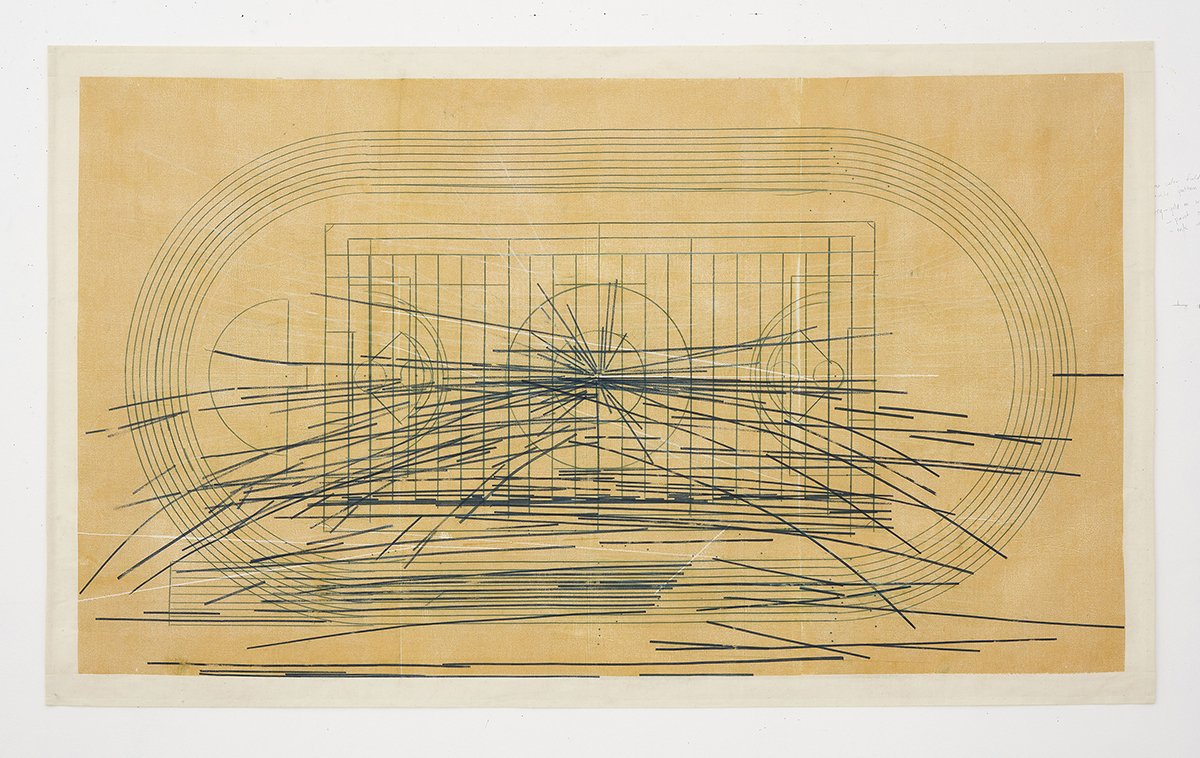

Ronny Quevedo, revolutions abound (Estadio Olímpico Atahualpa), 2019, wax on oak tag. Image courtesy the artist.

Ronny Quevedo, Revolutions Unbound, 2019, wax on muslin. Image courtesy the artist.

Quevedo also interweaves time and space through his art making processes. As the artist explained in person, many of the artworks in at the line are from the same “matrix”—an object that can be used to create an image or multiple images, like a printmaker’s plate—but in different stages of production. This is the case with revolutions abound (Estadio Olímpico Atahualpa) (2019), Revolutions Unbound (2019), and topografía lyr(ic)a (2019). To create these two-dimensional works, Quevedo first stacks together several layers of surfaces, such as dressmaker’s paper, muslin, and oak tag, then incises his compositions, and finally irons the top of the dressmaker’s paper to transfer a concluding layer of colored wax. [6]

Ronny Quevedo, el perimetro, 2017, gold leaf and silver leaf on dress maker wax paper. Image courtesy the artist.

Through this process, the artist asks his audience to question which work is the original and which is the copy, which work came first and which one came last. Furthermore, through this same process, the artist simultaneously abstracts and combines imagery of the Ecuadorian sports stadium Estadio Olímpico Atahualpa and Ecuador’s complex history from the Incan Empire to the present day. By displaying multiple surfaces as the final art objects—where other artists may alternatively display only one final artwork—Quevedo complicates Western notions of linear time and space. [7] Furthermore, the artist’s rapid, chaotic lines and scribbles throughout his works, like in el perimetro (2017), also insinuate non-linear movement in time and space.

Ronny Quevedo, Ulama, Ule, Olé, 2012, milk crates and zip ties. Image courtesy the artist.

Communication theorist Marshall McLuhan explains: “the medium is the message . . . because it is the medium that shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and action.” [8] The two hanging sculptures Ulama, Ule, Olé (2012) and the site-specific installation at the line (2021) fully relay Quevedo’s message about the complex movements and transformations involved in sports and marginalized communities. Ulama, Ule, Olé is comprised of two separate hoops made of multi-colored, plastic milk crates and zip ties. They are hung high above the at the line floor installation, forcing viewers to look up, crane their necks, and move around the hoops as players would in Ulama, a Mesoamerican ballgame played since 1400 BCE. [9] Subverting traditional materials, Ulama Ule Olé replaces the carved monumental stone goal with materials “that conjure makeshift basketball courts constructed from the mass produced and discarded [objects] of the [contemporary] urban landscape.” [10]

An overhead view of Ronny Quevedo, at the line, 2021, vinyl on gym flooring, 20 x 30 feet, commissioned by the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College. Image by Emma Powell.

At the line consists of differently-striped flooring from a basketball court—a floor we are usually able to walk and play on—obligating audience members to watch where they step, carefully skirting around the flooring in its new art gallery setting. In other words, these works are examples of how spectators must physically move their bodies to experience Quevedo’s notion of movement: an act that requires viewers to become active participants rather than passive observers. [11]

Ronny Quevedo, errantry (the benefit of being offsides), 2019, cement and metal leaf on linoleum tiles. Image courtesy of the artist.

Another example of this type of work, though not included in this exhibition, is Quevedo’s errantry (the benefit of being offsides) (2019). Made of deflated cement soccer balls and basketballs and metal leaf on linoleum tiles, errantry combines sculpture with site-specific installation and is displayed across the gallery floor—as shown in the exhibition Field of Play (2019) at the Open Source Gallery in Brooklyn, New York and the exhibition Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: Indigenous Space, Modern Architecture, New Art (2018) at the Whitney Museum in New York City . To experience the work, viewers must walk around and even step over the artwork depending on its placement in the gallery space.

Ronny Quevedo, installation view of Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: Indigenous Space, Modern Architecture, New Art at the Whitney Museum of Art, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

Moving our bodies differently while experiencing artwork is crucial when movement through time and space is conflated, especially when it is conflated for the purpose of highlighting colonialism, immigration, and displacement while reminding viewers that indigenous lives and cultures still exist. Although most of Quevedo’s artworks in at the line abstract the idea of movement through materials, processes, and compositions, they do not prompt the audience to move themselves. While this is a challenge in a traditional exhibition space—especially when most of the works are displayed in a procession along the perimeter gallery walls—if spectators were encouraged to move in different ways by these artworks evoking movement and immigration, they would embody the motions involved in colonialism and displacement and better internalize the artist’s message.

Mary Grace Bernard (MG, she/her) is a trans-media and performance artist, educator, organizer, and crip witch. Her practice finds itself at the intersection of performance art, transmedia installation art, art scholarship, art writing, curation, and activism. She is the founder of the digital contemporary art platform Femme Salée (F&S) and a co-founder of the semi-anonymous performance and curatorial collective Hexus. She holds a BA from the University of New Orleans and MAs from New York University and the University of Denver.

[1] Katja Rivera, “at the line Curatorial Statement,” Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College, 2021, accessed October 5, 2021, https://fac.coloradocollege.edu/exhibits/ronny-quevedo-at-the-line.

[2] Ananda Cohen-Aponte, “Latinx Artists Are Highlighted for the First Time in a Group Show at the Whitney,” Hyperallergic, August 28, 2018, accessed on October 5, 2021, https://hyperallergic.com/456710/pacha-llaqta-wasichay-indigenous-space-whitney-museum.

[3] Elena Fitzpatrick Sifford, “Space of Play, Play of Space,” Muhlenberg College, accessed October 8, 2021, https://www.muhlenberg.edu/media/contentassets/pdf/about/gallery/Quevedo_Catalog_4.pdf.

[4] Alice Gregory, “A Brief History of the Zoot Suit: Unraveling the jazzy life of a snazzy style,” Smithsonian Magazine, April 2016, accessed October 8, 2021, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/brief-history-zoot-suit-180958507/. The Zoot Suit Riots of 1943 were a series of conflicts throughout Los Angeles between zoot-suiters and the U.S. military. Qoricancha was the most important temple in the Inca Empire and the version rebuilt in the 17th century is located in Cusco, Peru, which was the capital of the empire. Via this connection, Quevedo ties together historical moments and places important to Latinx histories. To learn more about the Zoot Suit Riots, see Eduardo Obregón Pagán’s “Los Angeles Geopolitics and the Zoot Suit Riot, 1943,” Social Science History (24.1, 2000), 223-256, accessed October 11, 2021, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/32139.

[5] For more information about the history of Zoot Suits, read Kathy Peiss’ Zoot Suit: The Enigmatic Career of an Extreme Style (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014).

[6] From my interview with Ronny Quevedo on September 29, 2021. Oak tag is a flexible material akin to thick paper used in the clothes-making process.

[7] “Western” here refers to Australia, Canada, Europe, New Zealand, and the United States. We can contrast Western notions of linear time and space with an idea derived from disability studies called “crip time.” It highlights how Western societies tend to look at time and space in a linear fashion, i.e., from point A to point B; or, for example, bad health always gets better with help from the medical industry. You can read more about crip time in Alison Kafer’s book Feminist, Queer, Crip (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013).

[8] Marshall McLuhan, “The Medium is the Message,” Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964), accessed from MIT on October 5, 2021, https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/mcluhan.mediummessage.pdf.

[9] For more information about the Mesoamerican ballgame, see the Metropolitan Museum of Art essay “The Mesoamerican Ballgame,” by Caitlin C. Early, accessed October 5, 2021, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mball/hd_mball.htm.

[10] Elena Fitzpatrick Sifford, “Space of Play, Play of Space,” Muhlenberg College, accessed October 8, 2021, https://www.muhlenberg.edu/media/contentassets/pdf/about/gallery/Quevedo_Catalog_4.pdf.

[11] Active participation stems from the concept of phenomenology. It posits that if audience members are encouraged to interact with an artwork outside of the traditional gallery-viewing experience—a viewer standing in front of a 2-D or 3-D object and thinking about what the artwork means or only using their eyes to analyze the work—they are more likely to understand, relate to, and embody the artwork’s message. For more information on this idea, please see Don Ihde, Bodies in Technology (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002) and Sophie Anne Oliver, “Trauma, bodies, and performance art: Towards an embodied ethics of seeing,” Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies 24, no. 1 (2010), 119-129.