Margaret Kasahara

Artist Profile: Margaret Kasahara

Transforming the Everyday and Mastering Time

By Danielle Cunningham

If art is alchemy, then Margaret Kasahara is an alchemist. Using items like toothpicks, buttons, and her own hair, the multi-disciplinary artist elevates these objects through her art processes, transforming them from common to sacred. And she takes her wizardry a step further, sometimes seemingly stopping time through her transformations while also reminding viewers of time’s unstoppable passage.

Kasahara makes materials present as well, assuredly applying a minimalist, contemporary aesthetic to them, though her work is also influenced by the abundance of objects available for repurposing in our modern world. She is seldom constrained by any particular style. As she points out, “It’s more freeing to stay away from the limitations of labels and categories and to only think about the best way to realize a piece.” [1]

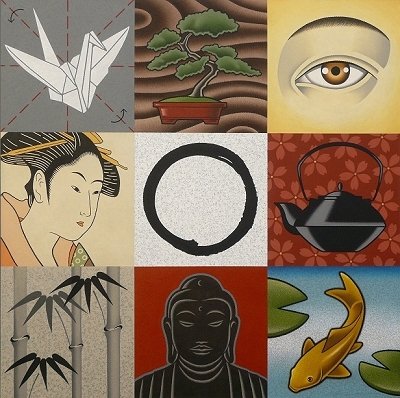

Margaret Kasahara, Foreign Accents, 2008, oil and oil stick on canvas, 48 x 48 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Born in New York City, but raised in Boulder, and now living in Colorado Springs, Kasahara faced exoticization in the 1970s as an Asian-American woman. She responded to this experience as a young painter and continues to respond just as she does to life in general: with hope, humility, and a seemingly relentless ambition to channel life into her work, plus an ever-present comic sense. As she sees it, her approach to art-making is an extension of how she processes the world around her, leading her to use non-threatening means such as humor to call into question the absurdity of life.

An installation view of Margaret Kasahara’s exhibition Between the Lines at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center from June 21 to September 28, 2014. Image courtesy of the artist.

Although she says it isn’t her intention to make political art, she recognizes the political implications of visually expressing her Asian-American, female identity. Her solo exhibition Between the Lines at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center in 2014 expressly delved into identity politics. It consisted primarily of large, flat paintings in which she interrogated overtly stereotypical Asian imagery such as Hello Kitty and koi fish. She also showed three-dimensional works made with kitschy objects like paper parasols and Chinese take-out containers.

Margaret Kasahara, Notation 22-21, 2021, 22-karat gold leaf on sushi rice and pencil on rag paper, 3.625 x 3.625 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Kasahara continues this interrogation into identity and materiality in her current Notation series (2016-the present). Using sushi rice, origami paper, and metallic threads, these pieces demonstrate her ancestry as well as her ability to bring out the hidden qualities of everyday objects to create new histories. Process is equally as important as materials for Kasahara. Hers can be likened to that of a meticulous craftsperson from a forgotten age, as she coats tiny grains of rice carefully in gold leaf—as in Notation 22-21 (2021)—and they gain what she describes as “a jewel-like quality.”

Works from Margaret Kasahara’s Notation series on view as part of the U OK? exhibition at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs Gallery of Contemporary Art from June 4 to August 6, 2021. Image by Stellar Propeller Studio, courtesy UCCS Galleries of Contemporary Art.

Rice, before Kasahara alters it, is a material that to many is unremarkable. As she notes, though, her process accentuates the “uniqueness and individuality of each grain,” making it costly and precious. Paired with intricate and time-consuming pencil strokes, as seen in the recent exhibition U OK? at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs Gallery of Contemporary Art, these works feel meditative and their production requires deep concentration and dedication. The space around the rice grains seems to glow, as it is accentuated by the darker, heavily-textured and penciled-in areas surrounding each grain, creating an air of sacredness. These works with rice also appear like petri dishes full of organisms that are ostensibly capable of multiplying.

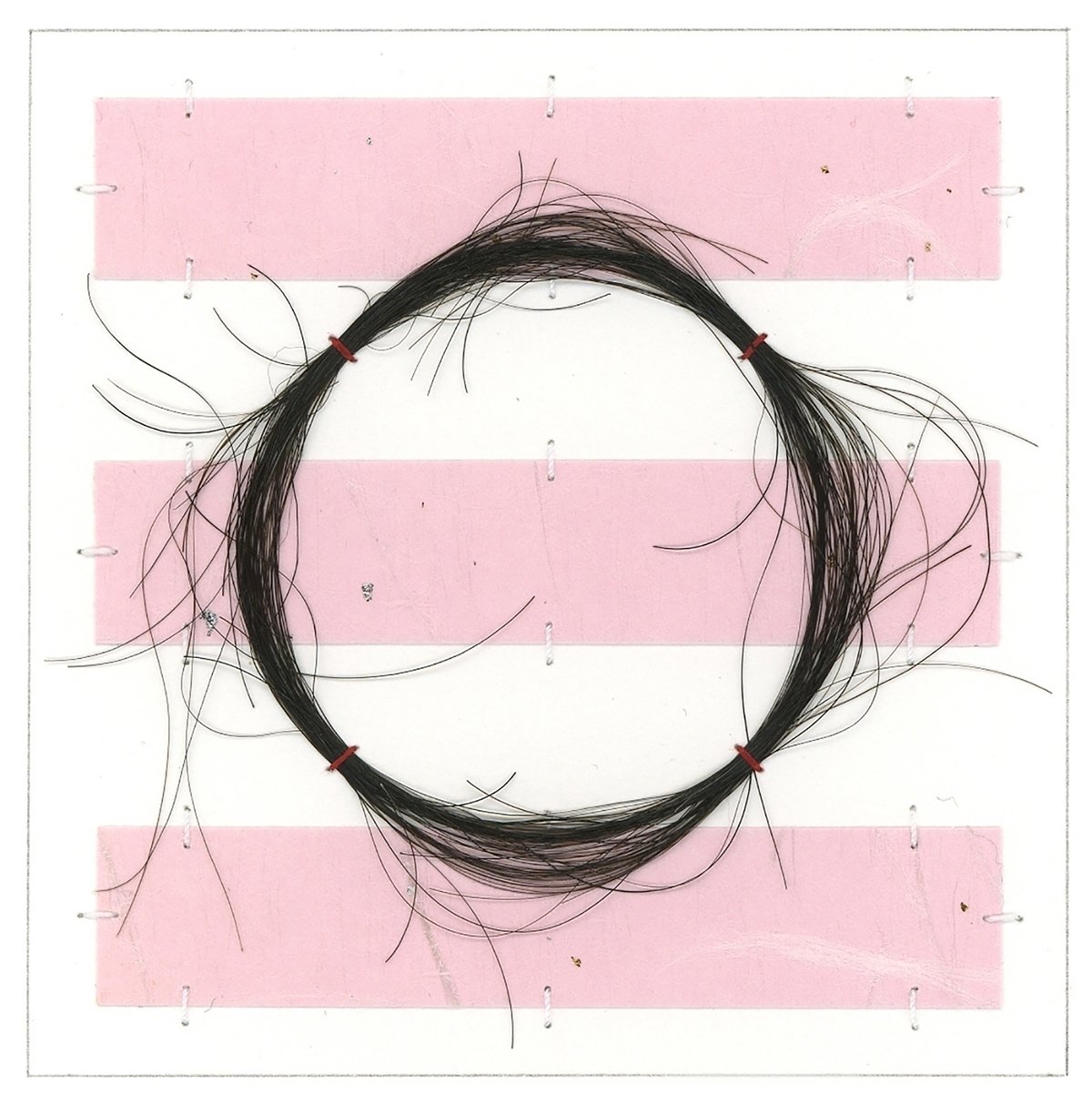

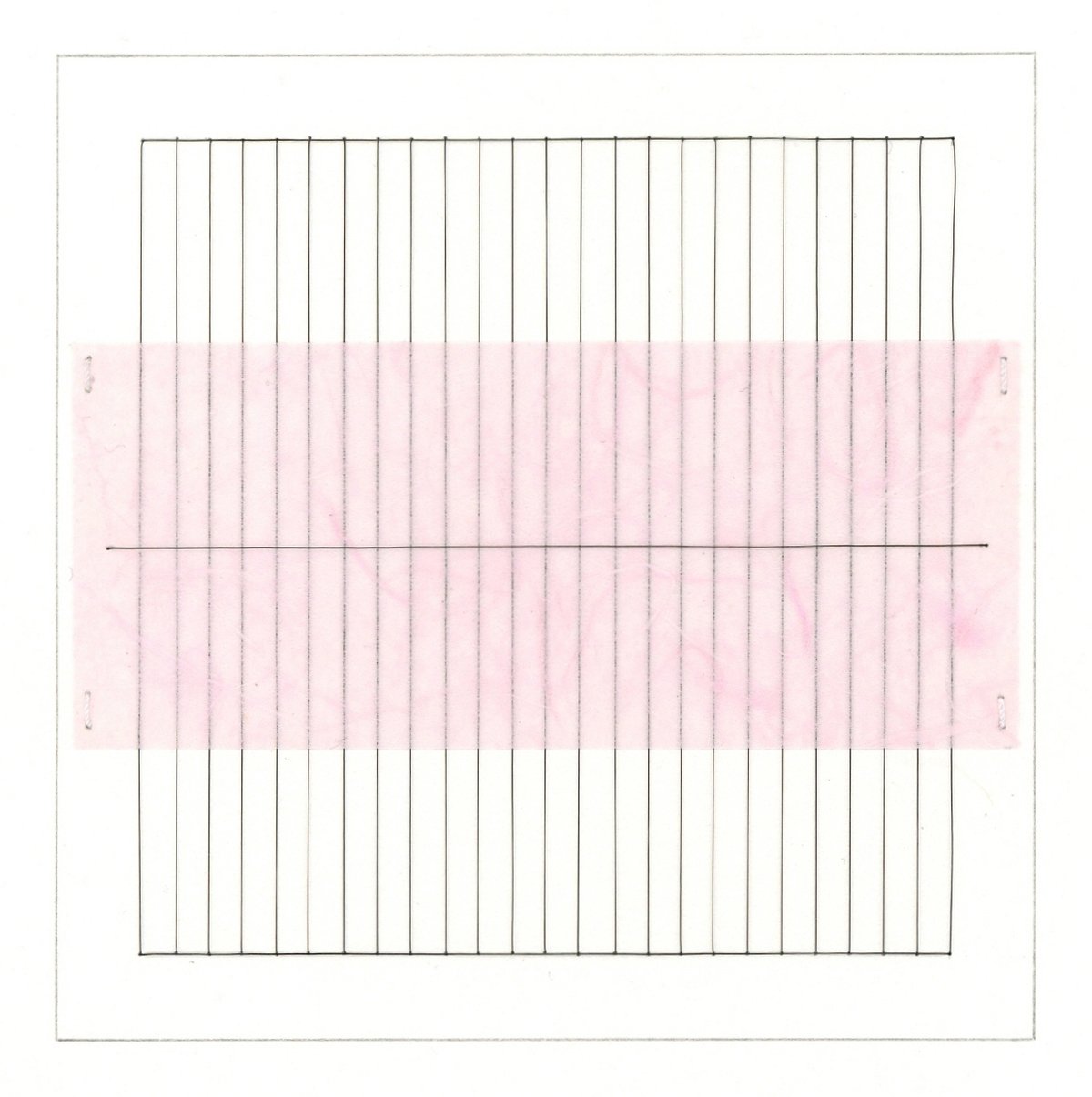

Margaret Kasahara, Notation 5-18, 2018, washi origami paper, artist's hair, thread, and pencil on rag paper, 3.625 x 3.625 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Rice isn’t the only ordinary object whose history Kasahara draws forth. Included in the Notation series are four delicate works made with strands of her own hair, pink paper, and thread, which she exhibited in the Pink Progression show at the Center for Visual Art in 2018. These pieces are deliberate acts reflecting the passage of time, for it takes years to grow a single strand of hair. Effectively, hair holds the history of its owner and it demonstrates that time is moving constantly forward.

Margaret Kasahara, Notation 121-17, 2017, Unryu paper, artist's hair, thread, and pencil on rag paper, 3.625 x 3.625 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

This makes Kasahara a controller of time, freezing individual moments as she fixes strands of her hair to sheets of paper. Hair is also a receptacle for DNA—a fact to which Kasahara alludes while framing her own body as a source for art media. In addition to these subtleties, the artist points out yet another, noting the commonalities between rice and hair since both reference heritage. By showcasing a myriad of objects in her work, she expresses her pride in her own ancestry, and that she is a keen observer and a keeper of memory, time, and culture.

Margaret Kasahara, Notation 130-17, 2017, Unryu paper, artist's hair, thread, and pencil on rag paper, 3.625 x 3.625 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Kasahara’s work is refined due to her technical skill and deeply thoughtful conceptual content. Her range of materials and the ways she combines them cause her to stand out and make her difficult to define as an artist, which is exactly how she prefers it. She exists outside of painting, drawing, or sculpture, and is instead a thoroughly modern artist—one who can utilize any and all media, and who never takes herself too seriously. In her own words, “It’s the work that matters.”

Danielle Cunningham is an artist, scholar, and independent curator living in Denver, Colorado. She writes from a critical theoretical perspective on topics including science fiction, gender, sexuality, and disability, with an emphasis on mental illness. Dani has curated numerous group exhibitions and is the co-founder of chant cooperative—an artist co-op in Denver. She holds a Master’s Degree in Art History and Museum Studies from the University of Denver.

[1] This quote and subsequent quotes come from my interview and correspondence with Margaret Kasahara in September 2021.