Deborah Jang

Artist Profile: Deborah Jang

Why not then a poem?

By Zoe Ariyama

The word that seems most apt to describe Deborah Jang’s sculptural works is “lyrical”—each piece is built from a motley assortment of disparate objects which, once together, find balance and rhythm. According to Jang, her constructions are a study in radical inclusion.

Deborah Jang, Moth to Flame, 2023, wall-mounted mixed media sculpture, 22.5 x 22.5 x 2 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Ceiling fan blades, a washboard, piano keys, a row of foosball players—she gathers these parts, many used and discarded, and unites not only the objects’ forms but their histories as well to create a new presence. “I want to create something that wasn’t there before, but encompasses the potential of all the parts,” explains Jang. “It is everything everywhere all at once.”

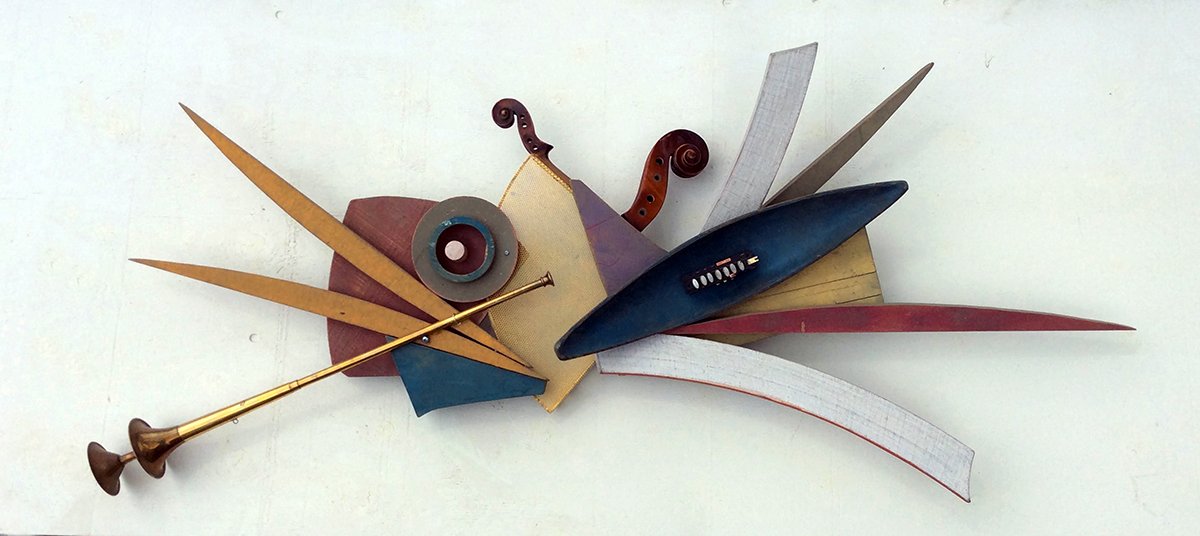

Deborah Jang, Row, 2021, wall-mounted mixed media sculpture, 63 x 27 x 4 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Jang’s artmaking process is largely improvisational. She experiments with arranging and rearranging materials, leading her to surprising forms. Sometimes the result is recognizable—a fish, a ship, a moth, a prickly pear—while other times the final artwork is rather a moment of stability found between the convened materials. Jang’s Row (2017) calls to mind a Rube Goldberg machine, carefully composed and on the verge of movement.

Deborah Jang, Horse with No Name, 2013, found metal sculpture, 48 x 40 x 18 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Jang earned a BFA in Visual Arts from the University of Colorado Denver in 1978, at the time focusing her artistic practice on painting. It was not until she took a metalworking class with her young son that she began her foray into sculpture. Welding, the act of joining objects, piqued her interest. Her early works are mostly of animals created by welding fragments of distressed found metal.

Deborah Jang, Spry, 2018, wall-mounted mixed media sculpture, 60 x 30 x 8 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

She now incorporates a much wider range of materials in her works, which she carefully collects from thrift stores, dumpsters, or the side of the road. Jang says she relates strongly to the Japanese aesthetic concept of wabi sabi—she believes in the beauty of the imperfect, worn, and aged. This trait isn’t new for Jang. Growing up, Jang says she was always the one picking the most lopsided, ugly pumpkins in the pumpkin patch.

Deborah Jang, Launch, 2023, wall-mounted mixed media sculpture, 18 x 21 x 3 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

The artist has an eye for the joyful and peculiar in the shapes distilled from the objects she encounters. Take, for example, the whimsical metal zigzag of an old potato masher with its handle removed found in Jang’s Launch (2023). Within the context of the sculpture, Jang calls attention to the often-overlooked humor in an everyday item.

Deborah Jang and Mark Friday, Sky Sign, 2019, mixed media sculpture, commissioned by Vickie and Brian Stevinson, owners of Art Gym. Image courtesy of Deborah Jang.

You may recognize Jang’s eclectic style from the Art Gym sign near Colfax Avenue in Denver, a collaborative design with Mark Friday, directing folks to the shared studio with a patinated, rooster-topped weathervane, a wagon wheel, and giant metal letters, reminiscent of the street’s iconic vintage signs.

Deborah Jang, Conundruminium, 2017, wall-mounted mixed media sculpture, 48 x 65 x 4 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

More recently, Jang expanded her creative practice to writing poetry and has published two collections, Float True (2020) and Last Will and Best Guesses (2022), with another on the way. Following the 2016 presidential election, Jang says she felt an increased sense of urgency in creating work that contended with the violent racism, xenophobia, and misogyny that seemed to be hitting a boiling point. In contrast to her sculptural practice, she needed a means to vocalize more explicitly all that was “raging inside,” leading her to turn to writing.

In Why Not?, Jang asks:

When salvation sputters

out taut haughty lips,

drenched in righteous lies,

When jowly men sit well-padded

making bleached out choices

for the children of the world,

When blood and bomb talk

mushroom over nightly news

casting shadows between nations

and their glory

When women, dark and dusty,

wail into silence made of sons

and daughters missing,

Why not then a poem?

Why not then most of all a poem?

Why not now a poem?

…

With support from mentors and workshops with other writers, she dared herself to be vulnerable in a new medium.

Deborah Jang, Hark, 2018, wall-mounted mixed media sculpture, 54 x 29 x 6 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

In her poetry, the personal is political. Through intimate reflections on familial memory, Jang delves into spirituality, resistance, and the slippery passage of time. She is a third-generation Asian American; her grandparents immigrated from China to the U.S. at the turn of the twentieth century, making the journey through Angel Island alongside thousands of others. In her poems “All-American Gong Girl: A Brief History,” “Guanyin to Lady Liberty,” and “Ode to yellow,” she sketches snippets of her family history and the tensions of Asian American identity—then and today.

The most heart-wrenching of Jang’s poems, though, are the ones centering on her love for her son and grandchildren, alongside ruminations on the end of life:

Trace Elements

1.

Lying close I count his toes

like rosary beads

This one went to the market

This one stayed home

His small steady breath

ekes my redemption

This one had roast beef

This one had none

My heart pressed to his

whelms over. Amen

Through the nighttime and

All the way home

…

3.

I snug you in my heart mind,

baby. Look up. I am the

hungry night.

Deborah Jang, Rock of Ages, 2021, mixed media sculpture, 33 x 24 x 24 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

The two artistic practices are complementary, even intertwined. Jang also notes that words can only go so far, which brings her back to the visual arts. During the summer of 2022, as one of several installations at a warehouse slated for demolition in the River North Arts District, Jang installed a series of chair sculptures and invited local poets to read from the ornamented seats. One blanket-backed rocking chair, Rock of Ages (2021), has two articulated arms with painted fingernails that extend around the sitter in a hug—a bit of support for when reading aloud.

Deborah Jang, Prayer Wheel (Five Points at the Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library), 2016, installation view, mixed media sculpture. Image courtesy of the artist.

Jang has called Denver her home since the 1970s and is deeply enmeshed in the local arts ecosystem. Besides teaching mixed media at the Art Students League of Denver, she consistently leads art projects with several community organizations in the Denver area. At The Gathering Place, a space serving women, transgender and non-binary individuals, and children experiencing poverty and housing instability, she leads workshops on screen-printing t-shirts with the students’ own designs.

Deborah Jang, Prayer Wheel (La Casita Community Center), 2016, installation view, mixed media sculpture. Image courtesy of the artist.

With a grant from the Denver Arts and Venues P.S. You Are Here program, Jang created a series of prayer wheel sculptures—which one can spin to send out goodwill—for installation in three Denver-area neighborhoods. For the prayer wheel in Westwood, Jang worked with the La Casita community center to decide which values to visualize on each wheel (grace, unity, faith, peace, and love) in the style of Mexican papel picado.

Deborah Jang, Guanyin (Kwan Yin), 2019, mixed media sculpture pictured with REACH studio artists at RedLine Contemporary Art Center. Image courtesy of the artist.

Deborah Jang, Guanyin (Kwan Yin), 2019, mixed media sculpture, 96 x 36 x 36 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

In 2019, in collaboration with the REACH studio artists at RedLine Contemporary Arts Center, Jang constructed Guanyin (Kwan Yin) (2019)—a figure of the bodhisattva of compassion—by combining independently created elements. The artists drew also from imagery of the Virgin of Guadalupe to create a syncretized, protective presence, now installed at The Mango House in Aurora.

Deborah Jang at work in her studio. Image courtesy of the artist.

Jang says her time working at summer art fairs booths is past. Wood and metal sculptures are heavy, and tents are hard to put up and take down each weekend. Instead, she exhibits at galleries and sells through her website. However, she is not slowing down as she gets older by any means; in fact, she may be the definition of a lifelong learner. As she follows her creative impulses (most recently trying her hand at letterpress printing), the artist says she keeps realizing just how much there still is to do. In her life and in her artistic process, Jang’s commitment to transformation honors the work of aging, remembering, and finding beauty in the unanticipated.

Zoe Ariyama (she/her) is a writer/reader currently located in Denver. She holds a BA in art history and political economy from Tulane University, and focuses on projects considering Asian American makers, institutional memory, and the oddities of the art market.