Todd Edward Herman

Artist Profile: Todd Edward Herman

The Forwarding of Embodied Ethical Viewership

By Mary Grace Bernard

When looking at artist Todd Edward Herman’s artwork, such as his 2007 film Cabinet, viewers must face images of death, the realities of physically disabled people, and the lives of mentally disabled people, among other non-normative bodies and minds. Herman creates films and photographs that deal with themes of the body and transience, representational taboos and spectatorship, and the historic consequences of othering. [1]

Todd Edward Herman, still from Cabinet, 16-minute film, 2007. Image courtesy of the artist.

Four years ago, Herman moved from San Francisco, California to Boulder, Colorado to be closer to family. He lives with his two children and runs a small art space called “east window” in Boulder. His art practice includes thirty years of working and collaborating with writers, performers, filmmakers, and curators to promote and advocate for bodies that are largely invisible in the public sphere.

In particular, his work closely examines the intimate lives of deviant bodies—bodies existing outside the public, white, hetero-patriarchal norm. [2] According to Herman, his work considers “how images compose, enforce, or undermine—rather than simply reflect—history, dominant values, identity, and authorship.” [3] In other words, he places bodies in relation to other bodies to create new conversations around how humans have told, presented, and retold history throughout time.

His works also evoke an “embodied ethical viewership”—a type of spectatorship that invites audience members to experience an “ethical face-to-face encounter with the Other.” [4] Revealing non-normative subjects in his art, he creates a confrontation between bodies and minds that are not just ethically but also emotionally and physically moving.

Todd Edward Herman, still from When I Stop Looking, 15-minute film, 2013. Image courtesy of the artist.

For this essay, I specifically examine Herman’s 2013 film When I Stop Looking. Using the concept of “embodied ethical viewership” in contemporary art, the artist challenges viewers with images of disabled bodies living with facial and cranial impairments. The film makes public what is often private—exposing the subjects’ visibly disabled/deviant bodies and minds. An audience that might otherwise disregard or choose not to see, understand, or feel must take in an experience of complex embodiment different from their own.

When I asked Herman what initially drew his attention to making films about complex bodies and minds, he replied, “I’m excited by the human form.” He continued, “We understand what's going on inside of us as well as around us because of and through the limits of human form.” [5] Indeed, as humans, we experience everything and everyone we know through and with our bodies. Just as the philosophical theory of phenomenology explains, humans absorb knowledge via our five senses: sight, smell, hearing, taste, and touch. [6] When two or more of these senses are engaged during an art experience, viewers are likely to better understand and take in more information.

When I Stop Looking places audience members directly in front of visibly disabled individuals’ faces and/or torsos. While at first the subjects seem fixed, like in a photograph, viewers eventually notice slight movements, such as breathing or a neck turning. The background is stark white, recalling the bright florescent lights in a hospital. After a few seconds, the image changes to the face of another individual. As more disabled people appear, viewers may recognize or feel their own uncomfortable, voyeuristic gaze while looking upon the subjects.

The interdisciplinary disability studies scholar Rosemarie Garland-Thomson has developed the idea of the “stare/gaze theory” based on the portrayal of disabled people—specifically people categorized as “insane” during the mid to late 1800s—in photography. She claims that taking photographs of those with disabled bodies and minds distances viewers from them and makes spectacles out of the non-normative subjects in photographs. [7] This is the experience, according to Herman, that many audience members may have while watching his film.

Todd Edward Herman, still from When I Stop Looking, 15-minute film, 2013. Image courtesy of the artist.

At the beginning of the film, all of the subjects’ eyes are closed or are turned away from the audience, which creates a one-way gaze of viewer upon viewed. Towards the middle of the film, however, the filmed subjects open their eyes, enabling a mutual gaze with the viewer. When the disabled individuals’ eyes meet those of the viewer, a type of emotional exchange occurs between them. As a result of this shared looking, Garland-Thomson’s stare/gaze theory no longer works. According to art historian Ann Millett-Gallant, “we live in a visual society, in which we are all pervasively gazing/staring at each other and forming our notions of ourselves both in identifications with and against other bodies.” [8] In other words, even in the stare/gaze theory, bodies are still in relation to other bodies.

This type of emotional exchange is what psychologists call “body empathy.” According to psychologists Delphine Grynberg and Olga Pollatos, “perceiving one’s body helps shape empathy.” [9] Using studies that asked participants to report on their demeanor in response to images depicting people in pain, Grynberg and Pollatos found that “the accurate perception of bodily states and their representation shape both affective and cognitive empathy.” [10] As such, the more a participant understood another person’s bodily experience—even in photographs—the more sensations (e.g. pain, arousal, or compassion) they felt in response.

Todd Edward Herman, still from Other People’s Stories, 8-minute film, 2011. Image courtesy of the artist.

Viewers also experience a type of body empathy in Herman’s 2011 film Other People’s Stories, which plays with the visceral experiences of embodied spectatorship. The film recounts the brutal murder of a disabled woman from Pennsylvania, narrates a woman’s sexual masochism, and depicts a woman orgasm to a room of anonymous onlookers. Ultimately, the film exposes private moments revealed to a public audience.

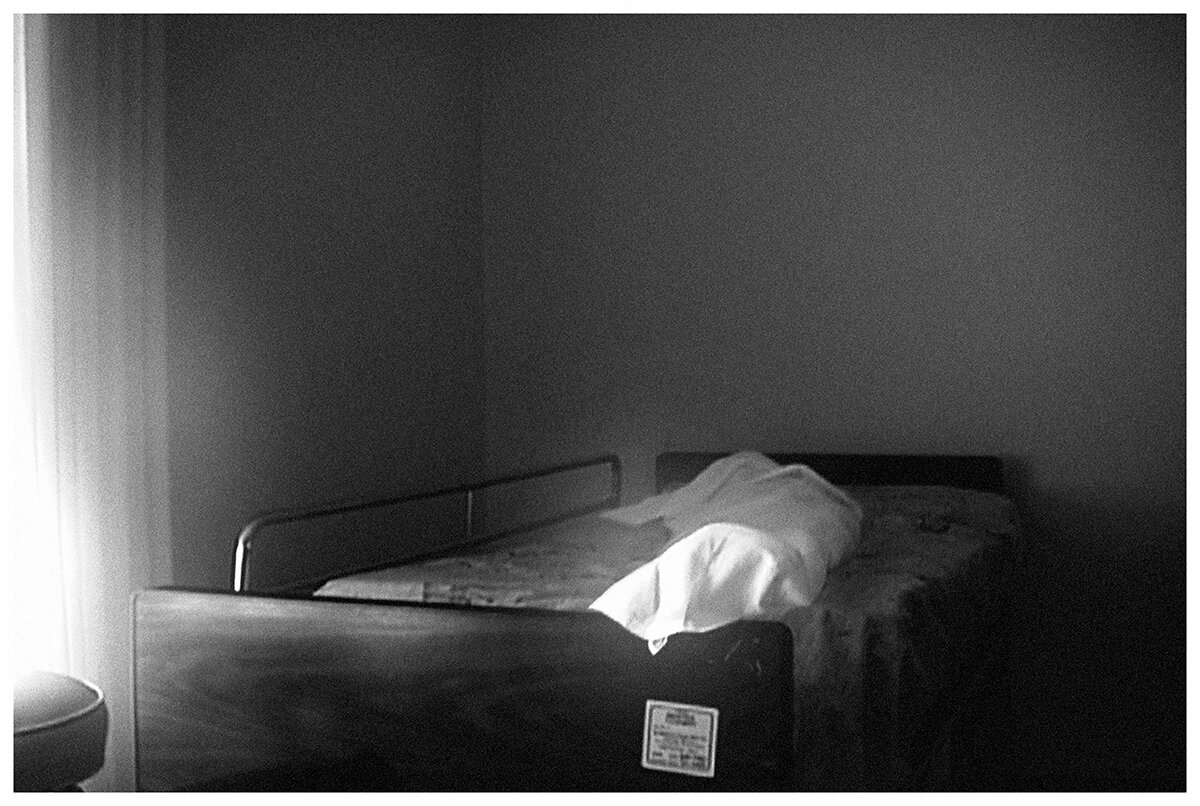

The artist’s 2007 film Cabinet follows the birth of his daughter and the death of his father. Similar to Herman’s film When I Stop Looking, the majority of Cabinet features slow moving subjects and images. However, instead of looking solely at human subjects in a staged setting, the artist provides viewers with intimate scenes of his parents’ home. He brings spectators into the private sphere. A few minutes into the film, audience members are met face-to-face with Herman’s father struggling to breathe with oxygen tubing in his nostrils. This moment lasts for an uncomfortable period of time.

Todd Edward Herman, still from Cabinet, 16-minute film, 2007. Image courtesy of the artist.

Sociologist Sophie Anne Oliver explains, when creating artworks that evoke body empathy “an ontological and structural model through which the concept of embodied ethical spectatorship might begin to be imagined.” [11] In other words, because human bodies and minds are always in relation to other humans and objects, spectators acknowledge their own embodiment in the moment of witnessing the “Other’s” trauma, pain, or any type of bodily experience, even in cases of mediated viewing. By sharing the experiences the filmed people live within their complex embodiments, Herman successfully imparts an embodied ethical viewership to his audience.

Producing films that call for an embodied ethical viewership is a socially-engaged art practice. According to the artist, his “socially-engaged work often takes the form of facilitating photography and filmmaking workshops and collaborations with artists as well as non-artists, kids, people with disabilities, and psychiatric survivors.” [12] While the films mentioned in this essay do not directly involve audience members, they do provide spectators with knowledge of embodiments different from their own and induce some type of emotion or bodily experience. As such, Herman’s works promote various narratives of justice, which often include disability.

Another socially-engaged art project Herman currently administers is his art space east window, located in Boulder, Colorado. As Herman explains, east window is “where elements of [his] personal art practice align with, extend to, and influence [his] curatorial decisions. . .by the inclusion of content and people who've been marginalized by the art world to a great extent.” [13] East window also features artists whose work responds to the intimate and personal as well as compelling social and political issues of our time. On view January 5-29, 2021 are prints from artist Chun-Shan Sandie Yi’s Crip Couture series—images of Yi’s wearable art that combines prosthetics and jewelry, as well as their wearers.

Mary Grace (MG) Bernard is a (dis)abled emerging artist, independent curator, and art writer living and working in New Orleans and Denver. She lives with cystic fibrosis, a chronic illness that informs her daily art and writing practices. She combines art theory and art practice in an effort to break down binaries and the relationships between the public and private spheres of experience. MG is the Founder & Director of Femme Salée, an innovative online art journal and zine dedicated to the voices working within exceptional art communities.

[1] Todd Edward Herman, Artist Biography, https://www.toddedwardherman.com/about, accessed 10.15.20.

[2] Merriam-Webster defines deviant as someone or something that deviates from a norm, especially a person who differs markedly (as in social adjustment or behavior) from what is considered normal or acceptably social; https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/deviant, accessed 10.15.20.

[3] Todd Edward Herman, “Statement,” Artnauts, https://www.artnauts.org/index#/herman-todd-1, accessed 10.15.20.

[4] Bree Hadley, Disability, Public Space Performance and Spectatorship, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 28.

[5] Author interview with Todd Edward Herman via email on October 14, 2020.

[6] For an in-depth understanding of phenomenology see: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/phenomenology/.

[7] Garland-Thomson explains her stare/gaze theory in the article “Seeing the Disabled: Visual Rhetorics of Disability in Popular Photography” found in The New Disability History: American Perspectives, ed. Paul K. Longmore and Larui Umansky (2001, New York: New York University Press, p. 335 – 374). She also discusses it in her book Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature (1997).

[8] Ann Millett-Gallant, The Disabled Body in Contemporary Art (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 6.

[9] Delphine Grynberg and Olga Pollatos, “Perceiving one's body shapes empathy,” Physiology & Behavior 140 (2015), 54-60.

[10] Grynberg and Pollatos, “Perceiving one's body shapes empathy,” 54-60.

[11] Sophie Ann Oliver, “Trauma, bodies, and performance art: Towards an embodied ethics of seeing,” Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies 24, no. 1 (2010), 125.

[12] Author interview with Todd Edward Herman via email on October 14, 2020.

[13] Author interview with Todd Edward Herman via email on October 14, 2020.