Laws of Nature

Tanya Marcuse: Laws of Nature

Denver Botanic Gardens, York Street Freyer-Newman Center

1007 York Street, Denver, CO 80206

November 19, 2023–March 31, 2024

Admission: $11.50 – $15.75; free for members and children 2 and under

Review by Madeleine Boyson

Witnessing the nutrient cycle is more than a practice for photographer Tanya Marcuse. The artist has venerated nature’s transience since at least 2005, when she began photographing fruit trees and their offerings. In her series Woven and Book of Miracles, on view in the exhibition Laws of Nature at the Denver Botanic Gardens’ Freyer-Newman Center until March 31, Marcuse lauds earth’s fertile excess in meticulous natures mortes, weaving life and death together in velvet-hued ritual.

An installation view of Tanya Marcuse’s exhibition Laws of Nature at Denver Botanic Gardens. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

The artist’s large-scale prints “evoke awe of the natural world,” as the exhibition text asserts. [1] But look closer—Laws of Nature enshrines our world, elevating decomposition to sacred, cosmic, and allegorical proportions. Marcuse grounds her work in the biblical Garden of Eden’s aftermath, while conjuring a threshold between fable and reality, fecundity and decay—life hastening and death arriving. [2] In collecting, compiling, and photographing what the poet Mary Oliver calls “a rich mash,” the photographer crafts tableaux that consecrate rot and regeneration, complicate natural laws, and relish the sensuous extravagance of an earth that is constantly remaking itself. [3]

An installation view of Tanya Marcuse’s exhibition Laws of Nature. Image by Scott Dressel-Martin, courtesy of the Denver Botanic Gardens.

Most of the works in Laws of Nature come from Woven (2015-2019), the third and final series in a fourteen-year-long project focused on composed nature, its aesthetics, and its symbols. [4] While the exhibition doesn’t require this context for viewing, Marcuse expands her ritual—and the final image—in Woven. Swapping four-by-five aspect ratios and inches for one-by-two, the artist opts for large-scale “tapestries of tone and texture” that accentuate detail and abstraction simultaneously. Marcuse photographs between thirty and fifty close-ups per work and digitally stitches them in post-production to create her final prints.

Tanya Marcuse, Woven Nº 16, 2016, pigment print, 62 x 124 inches. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

This scale and method allow the photographer to play with inspirations from art history. Woven Nº 16 (2016) opens the show with bursting pomegranates heaped amidst berries, pears, citrus fruits, apples, blossoms, twigs, and fallen leaves. The composition evokes seventeenth-century Dutch vanitas paintings and millefleur (“thousand flower”) tapestries of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, later reprised in Morris & Co. designs—both of which Marcuse cites as influences. Vanitas are a genre of still life painting that symbolize death’s inevitability and millefleur feature seamless backgrounds of individual plants and flowers. Characterizing both, Nº 16 suggests the French translation of “still life”—natures mortes—which literally means “dead nature.”

Tanya Marcuse, Woven Nº 30, 2018, pigment print, 62 x 160 inches. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Thanks to her production method, Marcuse’s photographs also flatten, but do not blur, her subjects in all-over compositions similar to mid-twentieth century abstract expressionist works. Woven Nº 11 (2016) recalls Jackson Pollock paintings (another influence) wherein paint drips are replaced by roots, cottonwood seeds, and sprigs. Each Woven work (save for the smaller “studies”) refuses single focal points and draws the eye “all over” in search of narrative or meaning.

A detail view of Tanya Marcuse’s Woven Nº 16, 2016, pigment print, 62 x 124 inches. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Yet, for a trained eye, Marcuse’s photographs do tell stories, even if the fables are elusive. The artist considers every aspect “both allegorically and aesthetically,” regarding an object’s symbolism as much as its color or shape. For example, mice represent evil. Pomegranates may recall Persephone in the Underworld, suggest fertility, or signal a king’s power. Sage, marigolds, and oranges might be antidotes to poison. [5] But strawberries also contrast with mud, and red mushrooms complement sea green caterpillars. The viewer must read the work as much as they are able. Marcuse merely reminds us that she, nature, and history have their own messages, even if we cannot interpret them.

Tanya Marcuse, Woven Nº 30, 2018, pigment print, 62 x 160 inches. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

On the tightrope walk between abstraction and realism as well as allegory and aesthetics, viewers are neither certain they’ve absorbed the whole picture nor convinced of its truthfulness. That’s because Marcuse delights in “elaborately artificial tableaux” that refuse to commit to life or death—or any other—binary. Life needs death and vice versa in Woven N° 30 (2018), which heralds luscious ferns even as it enshrouds a pheasant under snow.

Tanya Marcuse, Nº 2 Book of Miracles, 2020, UV pigment print on aluminum composite, 62 × 124 inches. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

The sumptuous arrangements in Woven are further bewitched in Marcuse’s latest series, Book of Miracles, begun in 2020. These works were created “in conversation” with the sixteenth-century German illustrated compendium of the same name and split into three parts: Kingdom, Portent, and Emblem. [6] Here the photographer crafts a ceremony in which viewers witness supernatural or heavenly phenomena borne of the earth, as in Nº 2 Book of Miracles (2020), with plants mimicking shooting comets amongst gold-painted snakes, moths, and flora.

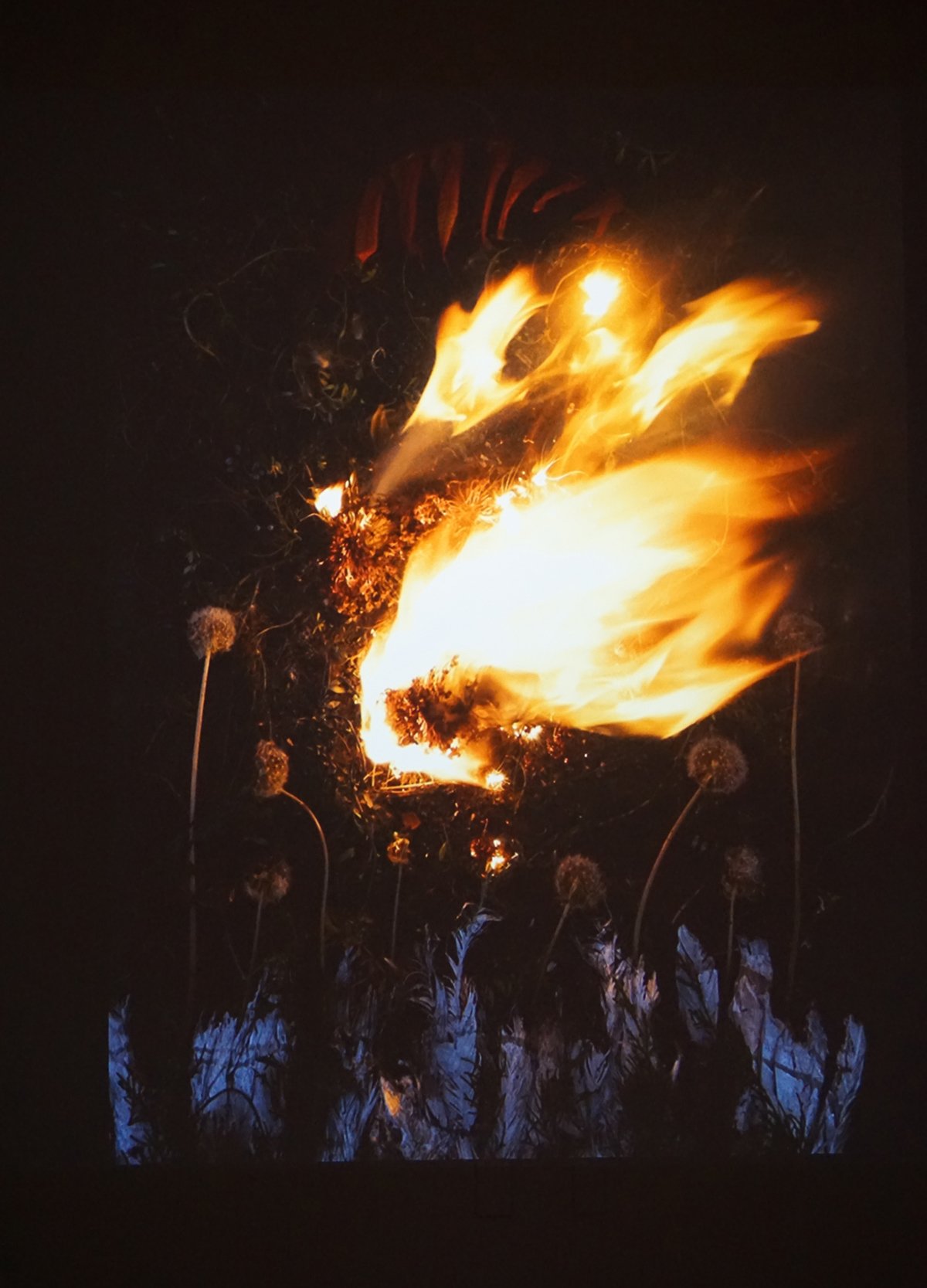

A still from Tanya Marcuse’s Untitled, 2023, from the series Book of Miracles, Part III Emblem, stop motion video, 10 minutes. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Elsewhere, a projector displays Marcuse’s ten-minute stop-motion video Untitled (2023) from Book of Miracles, Part III. Less abstract and more “fantastical,” these scenes “defy the laws of nature” and reveal shrines made of flora and fauna arrayed in gold, glitter, blood, smoke, fire, and bone. In one still, a piece of bark personifies outer space, confusing what is earthbound and what is celestial.

An installation view of Tanya Marcuse’s exhibition Laws of Nature. Image by Scott Dressel-Martin, courtesy of the Denver Botanic Gardens.

Marcuse’s reluctance to commit to a singular interpretation is in part due to her process. Where previous series add or subtract materials onsite, the artist makes many of these works on a five-by-thirteen-foot wooden stage, similar to an angled, raised bed. Over weeks or months, Marcuse adds, layers, arranges, burns, paints, and transplants her collected matter—sometimes fresh, sometimes frozen—only to let time craft her own variations. Mud freezes, fruit rots, cobwebs creep, seeds germinate, carcasses decay, and mold grows. The resulting artwork becomes a spell cast by Marcuse, nature, and time, which are sometimes the same thing.

An installation view of Tanya Marcuse’s exhibition Laws of Nature. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Viewers therefore must consider the exhibition title and where the laws of nature begin or end. Marcuse inserts herself in the mash’s rich drama, directing the scenes even if the players say unexpected lines. Does nature prevail despite human interference? Or, is humankind part and parcel of those same fates? In answer to both queries, Laws of Nature presents an apologia, a formal defense of nature’s “opulence which verges on excess, a plenty which verges on plunder.”

Madeleine Boyson (she/her) is a Denver-based writer, artist, lecturer, and curator whose work concentrates on American modernism, natural photography, and (dis)ability studies. She holds a BA in Art History and History from the University of Denver and volunteers as Development Director for Femme Salée—an online intersectional platform focusing on complex embodiment in the arts.

[1] All quotes come from the exhibition wall text or the artist’s website unless otherwise noted: tanyamarcuse.com/woven.

[2] “Life hasten[ing]” comes from the epigraph in Tanya Marcuse, Fruitless | Fallen | Woven (Santa Fe, NM: Radius Books, 2019). To read the entire quotation by Seneca the Younger, visit www.themarginalian.org/2014/09/01/seneca-on-the-shortness-of-life/.

[3] The phrase “a rich mash” comes from Mary Oliver, “Lines Written in the Days of Growing Darkness,” from the collection A Thousand Mornings: Poems (London: Penguin Books, 2013).

[4] Fruitless (2005-2010) serializes fruit trees on salable land near the artist’s home in the Hudson Valley. In Fallen (2010-2015), Marcuse zeroes in on the dropped fruits, layering them with plants, kitchen refuse, soil, leaves, insects, snakes, and flowers.

[5] For more information on plant symbolism, visit www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/467642, lithub.com/a-secret-symbolic-history-of-pomegranates/, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/467638, and www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378874104005306.

[6] The Book of Miracles (also called the Augsburg Book of Miracles) includes folios of biblical miracles, meteorological and astronomical portents, natural disasters, monsters, and proclamations of the advent.